“To tell you the truth, I don’t know. But I am going to write something.”

“And did anything else happen up there in Ketchum?” he wanted to know. “Anything you haven’t told me?”

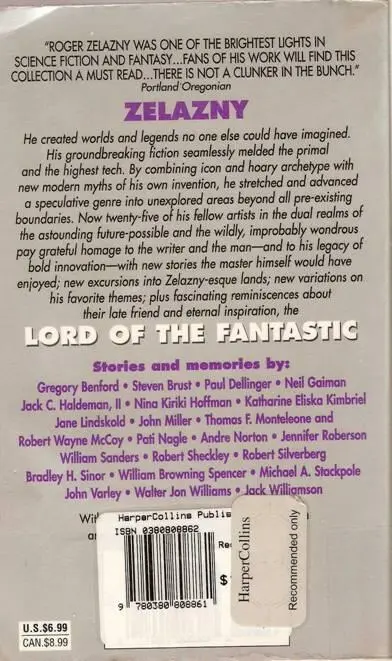

I thought about this for a while. We were sipping strong black coffee from the Blue Mountains of Jamaica and nibbling on Scottish scones that Roger had bought that morning at the bakery, and I watched the steam rise off his cup. His eyes were agleam, and I remembered that he had once told me the derivation of his name: it came from Poland, as did his family. Sparks thrown off by the hot iron of the blacksmith’s hammer. Roger’s eyes, sparkling with blue fire, reminded me that he himself was forged within the power of his birth name: Zelazny. Spark-maker, smithy of words.

“There is something I haven’t told you,” I recalled. “Something that someone said to me just before I left Idaho. It was weird, too. There was this old man at the airport, who came up to me and asked what I did for a living, and I mumbled, half-heartedly, that I was a teacher. And do you know what he said, that old man? He asked if I were a storyteller. And I told him that, being a teacher, I had to be. Then, while we waited for the plane, he told me a story. It was about a mountain man named John Colter, who ran half-naked across three hundred miles of wilderness while being pursued by half the Blackfeet nation.”

Roger said, “That’s worth more than the MacLeish poem, I’d wager.”

He said nothing more about this, and I did not mention it myself for at least a year. Then, one night, while we were having dinner together, I showed him the first chapter of John Colter’s race for life. Once again, we were sipping coffee. He smiled and put down his mug.

“That’s good writing,” he said.

“I wanted you to see it for a special reason,” I told him.

“Oh?” He took another sip of coffee, set the mug down again.

“I would like to know if you would write this tale with me, if we could possibly write it together?’’

“What’s the main thread?” he asked curiously.

“Two men,” I said, “two mountain men, John Colter and Hugh Glass. Colter, pursued by Indians, runs a hundred fifty miles to safety; Glass is mauled by a grizzly bear, and crawls an equal distance. That is about all I know at the moment. But I know that I want to write it with you.”

Roger’s interest seemed to cool before my eyes. He told me that he had so much to do, contracts to fulfill for books as yet unwritten, and there was just no time for this one. “Maybe in a few years,” he said. Then he changed the subject to what a good book Islands in the Stream had turned out to be, and how much he liked the poem by MacLeish. And that was all he said about Colter/Glass for quite some time.

Then, one day, two years later, while we were discussing an audio project of his which I was busy putting together, he showed me something that he was working on. At the top of the page was the word “Glass.” Amazed, I read on, discovering that this was chapter two of the novel I had proposed that we would write together, a book about two men fighting their own personal daemons in the American West; one turning hawk, the other turning bear, both switching identities somewhere near the end of their travail, so that Colter crawled upon his belly and Glass danced across the snow.

I remember well the day we finished the book. Well, it wasn’t “we,” it was “he.” For when I received the last sheet of typing paper from him, he had written something at the bottom of the page. It was there in his neat and tidy, scrunched-down script: “Wherefore the rest is silence.”