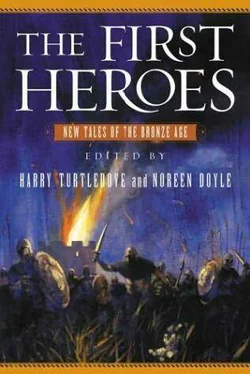

Гарри Тертлдав - The First Heroes

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Гарри Тертлдав - The First Heroes» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The First Heroes

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The First Heroes: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The First Heroes»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The First Heroes — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The First Heroes», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As the short, light night, that is hardly night at all, whitens toward day, my lady and I follow the trumpeters up onto the hillcrest. There I look past two plank-built crafts a dozen logboats drawn ashore, westward and outward. Already the water gleams like molten silver. Across it, Longland and, far ther off on my right, Yutholand are still darkling. Clouds loom huge and murky beyond them. A stiffening wind whines and bites. It has raised chop on the straits. Even this early, the seafowl, gulls, terns, guillemots, auks, are fewer than I have formerly seen. Their cries creak faintly through the wind.

Will a rainstorm drench the balefires—again?

We turn around and take our stance, the trumpeters side by side, I on their right with a spear held straight, Daemagh on their left with fine-drawn gold wrapped about the holy distaff. Now I am looking east, widely over our great island, past the massive-timbered hall and its outbuildings, past the clustered wattle-and-daub homes of my folk, past their grainfields and hayfields and paddocks, on to the forest. Thus far the sky yonder is clear, a wan blue from which the few faint stars of midsummer have faded, and treetops shine with the oncoming light.

Below the hill, the people stand gathered, not only those of the neighborhood but outlying farmers, herders, hunters, charcoal burners, and others, some with their women and small children along, come together for the blessing and the fair, the feasting and dancing, merrymaking and lovemaking and matchmaking that ought to be theirs. As yet I cannot make them out very well, but I feel their eyes. Several are my guests at the hall, the rest have crowded in with kinfolk; all, though, are Skernings, and today one with me.

The sun rises above the forest. It sets the disc-shaped trumpet mouths ablaze like itself. My lady's bronze beltplate shines as bright, her amber necklace kindles with its own glow, and my cloak of Southland scarlet becomes a flame. Kirtles, breeks, blouse, skirt, headgear, the best we have, taken from their chests at times such as this, lend their softer hues to the sunrise. The trumpeters set lips to mouthpieces; the deep tones roll forth, hailing the sun at her height of the year, overriding the wind.

Suddenly—it has happened before—I am not altogether Havakh, son of Cnuath, nor is Daemagh altogether my wife and mother of my children. These are not altogether Saehal and Eikbo between us, who have been taught and hallowed to play at the holy times but are otherwise a farmer and a boat-owner. As they stand here with the trumpets curling mightily over their shoulders, one left, one right, and above their heads, the gods take us four unto themselves.

The sun swings higher on the tide of the music.

It ends, ringing off to silence. I lift the spear, Daemagh the distaff. We cry the words that were cried at the beginning of the world.

The wind seems to scatter them.

And then we are merely the lord and lady of the manor and two men. We start back down to carry out the rest of the day and the following night. By now the light overflows, though somehow it is as unseasonably bleak as the air. I see all too clearly how thin the millet, emmer, and barley stand in the fields, the grazing kine and sheep not fat; and I know all too well that the pigs have lean pickings in the woods. Let the weather hold till tomorrow, only till tomorrow, I pray. But I do not promise an offering if it does, for such vows have done little if any good in the past score or worse of years.

Maybe it will. At least this isn't as bad as the spring equinox. Then, when I plowed the first furrows, wind, rain, and sleet lashed my nakedness, I could barely control the oxen, my left hand shook so, holding the reins and the ard. Leaves were scant on the green bough in my right hand. After I came home, I shuddered between sheepskins for a long while.

Fears ill become the lord of the Skernings. I straighten my shoulders and my heart and stride downward with my companions.

Men mill around and greet me. I reply to each by name, and ask those whom I seldom see how they have been faring. There is more to being a lord than leading the rites, taking the levies, judging disputes, sustaining the unfortunate, going armed against dangerous wild beasts or the rare evildoer, and otherwise upholding the peace and honor of the domain.

Savory odors drift to my nostrils as I near the hall. Now my lady and I shall provide the morning feast. Afterward come the giving and receiving of gifts. Both will be meager, set beside memories of past holy days. Even the king's yearly procession around Sealland is less showy than it used to be, and no longer lavish. Still, no one is in dire want, my own coffers and storerooms are far from empty, and—at least this year—the folk need not crowd inside out of the rain but can spread themselves over the grass in the sunshine, freely mingling while they enjoy the meat and ale.

"Happy morning, Lord Havakh."

The hoarse voice jars me to a halt. There stands Bog-Ernu. How long since he last trudged the weary way here to take part in anything!5 I reckoned that a sullen pride kept him away. He was too poor to bring more than a token gift. When I gave him something better in return— which I must, of course, not to demean myself—it would lower his standing further yet. Men might not openly mock him, but their eyes would. So he, his woman, his children, and a few others like them have stayed apart. Three or four times a year, a trader or two comes by for the peat they have cut and dried, and maybe dickers for some pelts they have taken; else they are mostly alone. They hunt, trap, gather, and herd pigs in the forest, they grow a little grain in grubbed-out plots, and whatever Powers they offer to are not likely our great gods.

It has not always been thus with him. A tide of memory rises in me. My words seem to come of their own accord. "Happiness to you, Ernu—old crewmate—" They break off. Another man has thrust forward from behind his broad back. A snaggle-toothed grin stirs Ernu's unkempt, greasy beard. "You know Conomar too from those days, nay?" How could I forget? Conomar the Boian says nothing, only stares straight at me, but the hatred in that gaze has not changed.

"Well—well, he shall partake, since he's with you," I answer lamely.

Glee throbs. "You'll be glad, my lord."

They stand there in their stinking wadmal and birchbark leggings like a clot amidst clean, well-clad, well-groomed people—these two, and three more, younger, whom I suppose must be Ernu's sons. Flint knives at the belt are common enough among commoners, but theirs are crudely homemade. Despite the ban on killer weapons at folkmeets, the staves they grip could easily shatter skulls. Nevertheless they are Skernings, with that much claim on my hospitality and justice— except for their captive wolf—and once Ernu fared and fought at my side.

I give him a nod, turn, and continue to the hall, unheeding of anyone else. Memories are overwhelming my soul. Why? It is almost as if something beyond myself is calling them up, seeking to understand.

Oh, we were young when we set forth, all of us except Herut, and he just a bit grizzled. However grim our goal might prove to be, for us the venture began joyously. New lands, high deeds, fame to win and maybe wealth to regain!

But we were not callow. As the second son of Lord Cnuath, I was of course in command. Yet I meant to heed the counsels of Herut, a skipper who had thrice made the first part of this journey as well as plying our more usual trade routes. Besides, I'd already been on a few voyages myself. Mainly they were short, among the familiar islands or to Yutholand, but one went across the Sound and north along the coast yonder as far as anybody lived who shared our ways, while another went clear over the Eastern Sea to trade with the colonies.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The First Heroes»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The First Heroes» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The First Heroes» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.