Morning finally arrived. Dim sunlight revealed lifeless hunks of blackened metal drifting everywhere on the river. In scattered rows, circles, clumps, they reflected the cold, colorless light, and the air was suffused with the decaying odors of autumn. The city-dwellers brought forth cranes to retrieve the wreckage of the submarines from the river and trucked the pieces to scrap metal yards. The whole process took over a month.

After that, no submarines came to the Yangtze River.

As the Last I May Know

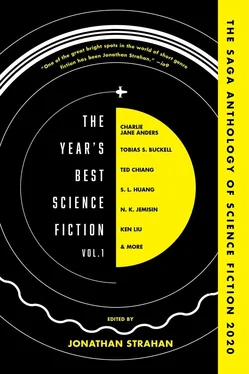

S. L. HUANG

S. L. Huang (slhuang.com) is an Amazon.com bestselling author who justifies her MIT degree by using it to write eccentric mathematical superhero fiction. Her Cas Russell series includes the novels Zero Sum Game, Null Set , and Critical Point , with her first book outside that series, Burning Roses , to come this year. Her short fiction has sold to Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Strange Horizons, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction , and elsewhere. Huang is also a Hollywood stuntwoman and firearms expert, and she has appeared on shows such as Battlestar Galactica and Raising Hope . Her proudest geek moment was getting killed by Nathan Fillion. The first professional female armorer in the industry, she’s worked with actors such as Sean Patrick Flanery, Jason Momoa, and Danny Glover, and been hired as a weapons expert for reality shows such as Top Shot and Auction Hunters .

A growing crowd of protesters trudged doggedly through the flurrying snow, bundled up into roundness against the cold until they resembled determined beetles. Back and forth they went, marching in a wobbly loop, their heads down against the wind but their voices strident as they fell into a chant:

Don’t kill children, kill the seres!

Before we all destroy ourselves!

Up in the window of the garret three stories above, Nyma watched them trundle and call. They didn’t have a very good chant, she couldn’t help thinking. “Seres” wasn’t even a hard word to rhyme— fears, years, tears…

She leaned her forehead against the window pane. The glass was cold.

She hadn’t yet felt the presence of her tutor in the doorway behind her. In truth, Tej had opened his mouth to speak out several times, only to swallow back the frigid air instead. He was, if he were to scrape away any illusions—and Tej was not a man who lied to himself, when he could avoid it—trying to best himself in a moral struggle.

He failed.

“You shouldn’t watch that,” he said to Nyma. Peace help him, but the garret was freezing. He folded his hands into the sleeves of his robe, wondering how Nyma wasn’t shivering.

Children were always so resilient. Too resilient.

“It’s my job now,” Nyma said into the window, the words fog on the pane.

“It doesn’t have to be.” Now that he’d broken, the words tumbled out of Tej like they wanted to barb into the child’s heart and keep her here. “You understand that, right? You can—you can say no.”

Nyma knew. Her tutors had taught her: she would always have a choice. But they’d also taught her why her duties were so vital, and why those duties had to be done by someone young, if not her then one of her classmates.

And she believed them. She believed in the Order and everything it stood for.

Dying scared her. A lot. The idea of it was so impossibly big and black that she couldn’t even hold it in her head. But it didn’t scare her enough to break the faith—not when her name had been the one drawn.

Of course, the news feeds said she shouldn’t be allowed to choose this life at all, blasting the Order for following the old ways. Ten-year-olds are too young to agree to this; they can’t make that decision for themselves; it’s inhumane! Some of those people wanted the Order disbanded. Some of them wanted only adults to follow its dictates, people who had passed the magic threshold of being able to say yes to saving the world.

Those same news feeds were markedly less certain whether butchering the Order’s traditions should also mean dismantling the nation’s stockpile of sere missiles.

“You taught me,” Nyma said to Tej. “It’s important. We’re important.”

Not as important as your life, Tej wanted to cry, wanted to fold her into him like his own daughter instead of one of his pupils, even as that betrayed every fiber of what he’d always fought for. “It doesn’t have to be you,” he managed instead. “We didn’t know it would be like—this. You can say no to it. To him.”

Nyma turned from the window, her freckles blotching dark on her pale skin, her eyes so large they took up half her face. “He’s scary,” she whispered. “Will you come with me? When I have to meet him?”

Tej had to turn away, then, because it wouldn’t do for Nyma to see one of her tutors weep.

Nobody thought Otto Han would win the election. He was the quiet outsider candidate, the one who’d kept pecking at his place in the polls until he rose up when all the others had shouted themselves out.

He wasn’t even the one who had most worried the Order, at first—that honor had gone to the demagogue candidate who fanned the flames of mounting war until her supporters screamed in violent ecstasy. She had burned out brighter and faster than the swell of rage she had dug from the populace. The tension in the Order had fallen into palpable relief when she’d plummeted in public opinion, even as she’d left behind a smear of angry demonstrators yelling, “ We have seres, we should use them!”

They didn’t understand, those people. They had forgotten. The Order was built not to forget.

It wasn’t until two weeks before the election that a reporter asked Otto Han his opinion of sere missiles. “I think if it makes the most military sense for the protection of our nation, we need to use every tool at our disposal,” he’d answered. “We’re at war. Everything should be on the table.”

The reply sparked panic in the Order, but got far too little notoriety elsewhere. The Order Elders wired their contacts in the feeds, begging other newsfolk to press Han hard and ask the important questions, before it was too late:

How can you justify a weapon that will vaporize an entire city in a single instant—buildings, children, hospitals, prisoners of war, millions of innocent civilian people, everything for so many hundreds of miles—gone? How is that not a war crime?

How can you reconcile that with history, our history, as the only country in the world who has had sere weapons used against us? How can you do what we have always considered the unthinkable?

And, the most relevant one to a ten-year-old Order girl and those who knew her:

Do you truly wish to use such weapons so badly, that you would be willing to do as the law requires and murder a child of your own land with your own hands in order to gain access to them?

But there hadn’t been time. Nobody had asked Han any of those questions until after he’d already won.

The poem Nyma returned to most often had been written by Akuta Myssoutoi two hundred years ago, after he’d lost everyone in his family in the destruction of the Capital.

The snow falls over nothing.

I beg three small graves to place incense

But echos have no tombs.

The bleakness of it had been a touchstone for the beliefs she’d been raised with, a reaffirmation of the Order’s righteousness.

Now the words of that final stanza kept circling in her head, echoing dully. Behind them loomed the granite image of President Otto Han, standing above her with a knife, his hands soaked crimson with her blood.

Читать дальше