He rubbed his face again and then said reluctantly, barely forcing out the words, “I hope you are aware of all the consequences of your decision, all its meanings, its side effects? You will have to go through childhood and adolescence, to grow up, to live and live – hoping that your destiny will somehow intersect with hers or his… I suppose you feel, albeit subconsciously, the boundless naivety of such a hope – having in mind the grouping of the B Objects and everything that happens in the Cloud – a naivety comparable to your enemy Brevich’s belief that things would always turn out the way he wanted. You are adjusting the probability of facts according to the yearning insistence of your faith, your desire – this is just the opposite of what a man of science should do. You…” And Nestor enunciated each word with the palm of his hand, “You are acting like some poorly educated – I’m not afraid of using this word – barbarian!”

“Well,” I murmured, “I have heard that we often resemble our worst enemies. Otherwise, we’d be lacking common ground for hostility. As for my choice, I didn’t have much of a choice. I simply felt I had to do the only right thing.”

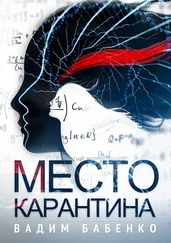

Nestor did not respond; he might not have even heard, did not want to hear me. He was reiterating his own point – monotonously, stubbornly: “And I also thought that, besides rational arguments, your fears would stop you. The ones we talked about: for example, the fear of never meeting your Tina – do you understand how scant the chance of such an event is? Or the fear of failure – who knows what will happen in your second life, who you will become, what you will be able to achieve? And then: Are you one hundred percent sure there will even be a second life? Where you are going? From what, from where? What this place really is, the place of Quarantine? Have you ever thought that this, perhaps, is basically all that’s left for you? What if Quarantine is a computer simulation or, say, the last fantasy of your fading mind, which has been artificially prolonged – you may be in a coma from which you’ll never wake up? And still, you’ve decided to take the risk…”

He paused and somewhat ridiculously, angrily, threw his hands in the air – as if signaling he had run out of arguments. As if showing he had nothing else to contradict my stupidity.

But now, it was me who had the arguments. “Yes,” I said, shrugging. “All this, one way or another, has occurred to me from time to time. Yes, there were fears – and it was you who helped me overcome them. And I am very grateful to you, Nestor!”

My counselor focused his gaze on me. He stared at my face intently, then, gruffly, somewhat arrogantly, asked, “In what way? Let me know, if you’d be so kind, how I helped you?”

“Through your example,” I spread my hands. “What else? Through echoes of your history, its shadows. Everything that made me understand that I, in some hardly formulated sense, am by no means a pioneer. There were others before me – for instance, someone was engaged in cosmology, wrote literary passages, yearning for a woman waiting in some unknown space-time, tried to break out of the social matrix, was laughed at by his own family… If it weren’t for him, I would perhaps have been afraid quite differently.”

Nestor was suddenly embarrassed, turned his head, began to hide his eyes. Then, little by little, he mastered himself. He groaned, cleared his throat and said wearily, “Let’s assume we have outlined our positions – in general. I understand your motivation. Not that I accept or like it…”

For a while we sat in silence, both deep in thought, then he said, “Well… ‘Right now’ won’t work; you’ll have to wait. As with your rescue from the utility zone, the procedure is clearly defined; it cannot be speeded up. But we can initiate it immediately, why not.”

“I’ll probably need some special sanction?” I asked. “ Your sanction – I remember, you said you are responsible for assessing my ‘recovery,’ so to speak, my suitability for a new life.”

“Yes, it is needed,” Nestor nodded, “but in this case, it is a mere formality. I have no reason to deny you the approval. If I did, I would probably be suspected of some personal motive…”

“And what about my enemy?” I persisted. “You know that I have an enemy.”

Nestor frowned, “You mean revenge? Don’t worry, this intention of yours is completely innocent. All your intentions and you yourself are completely innocent, Theo, whether or not you think otherwise. So…” He folded his hands in front of him and again rested his gaze on me. “So, it’s goodbye; we can start the process. And that means… Goodbye!”

“You’ve just said goodbye to me twice,” I muttered. “Although it’s not customary to make long farewells here.”

I didn’t want to poke fun at him; I felt quite uneasy myself. It was clear: the procedure, having begun, could not be stopped. Until the very end.

“Yes, it is not customary…” Nestor agreed and again became pensive for a while. His shoulders sank; even his face sagged slightly. He no longer wanted or was able to hide his disappointment.

Then he suddenly shook himself, repeated once again, “Well, goodbye!” – and disappeared. The screen flickered; gray stripes and vague figures appeared on it. In a minute, they were replaced by the word “SOON.” I looked around and saw the room beginning to change. Almost immediately my head started to spin…

And now there are – just the remnants of reality around me: the window with the view of the winter park, walls without doors, and also – a viscous web of time intervals of which I have long since lost count. Their duration is uncertain, the boundaries between them blurred; the passage of time is the strangest thing that is happening now, at the end of Quarantine. At first, it was slightly eerie, then it became easier. Either because I got used to it, or I’ve just gotten older.

I walk around the room, along the wall with the same unchanging pattern to the window with the frozen picture. Farther on – to the closet whose door does not open. Then – to the bathroom, where everything is dead: there is no water, no shower; the toilet lid is tightly closed. I limp slightly; my left hip joint hurts. Recently, I complained about this to Nestor. He was surprised, “Well, what did you expect?” “Nothing else,” I’d agreed. “It’s as it should be.”

When my former counselor visits me, we talk amicably. Not getting angry, not trying to insist on our point of view. Our egos are lying low – at least mine is. Or maybe I just want to think so. Each time he says a lengthy farewell – as if in defiance of the customs of our past sessions. And each time I don’t know if I’ll ever see him again.

Occasionally we still tease each other, though. I told him once, jokingly of course, “You know, Nestor, I have always believed that cosmologists have a hidden handicap. An objective one, related to the scale of the quantities they deal with: just think about it – parsecs, millions of years, calculations in completely wild degrees by any normal standards. What is a human, if we are talking some sort of ten to the twentieth? The most appallingly terribly insignificant speck!”

Nestor, naturally, replied in a similar tone – my provocation was obvious. “I’ve often thought in a similar way,” he said, “about those who work at a quantum level. They never dare to raise their heads to look around; their triumphs and catastrophes have nothing to do with what’s happening in the real world. What is humanity to them – and at what scales do they search for their answers? The same degrees, only with a minus sign? Ten to the minus twentieth, if you round it up?”

Читать дальше