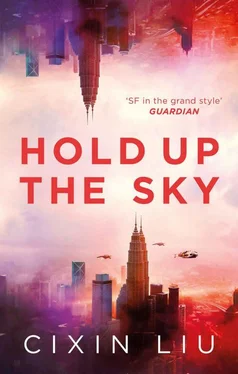

Лю Цысинь - Hold Up the Sky

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Лю Цысинь - Hold Up the Sky» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2020, ISBN: 2020, Издательство: Head of Zeus, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hold Up the Sky

- Автор:

- Издательство:Head of Zeus

- Жанр:

- Год:2020

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-83893-763-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hold Up the Sky: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hold Up the Sky»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Hold Up the Sky — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hold Up the Sky», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Kalina knew that in the battle that had just ended, the two sides had sent perhaps over ten thousand tanks into battle along the front, and half as many armed helicopters.

At that point they arrived at Arbat Street. The popular pedestrian boulevard of yesteryear was empty now, sandbags walling off the entrances to the antiques shops and artisans’ places.

“My steel darling gave as good as she got.” The lieutenant was still stuck on the morning’s battle. “I’m sure I hit a Challenger tank. But most of all, I’d wanted to take down an Abrams, you know? An Abrams…”

Kalina pointed to the entrance of the antiques store they had just passed. “There. My grandfather died there.”

“But I don’t remember any bombs getting dropped here.”

“I’m talking about twenty years ago—I was only four then. The winter that year was bitterly cold. The heating was cut off, and ice formed in the rooms. I wrapped myself around the TV for warmth, listening to the president promise the Russian people a gentle winter. I screamed and cried that I was cold, hungry.

“My grandfather looked at me silently, and finally he made up his mind. He took out his treasured military medal and took me here. This was a free market, where you could sell anything, from vodka to political views. An American wanted my grandfather’s medal, but he was only willing to pay forty dollars. He said Order of the Red Star and Order of the Red Banner medals weren’t worth anything, but he’d pay a hundred dollars for an Order of Bogdan Khmelnitsky, a hundred fifty for an Order of Glory, two hundred for an Order of Nakhimov, two hundred fifty for an Order of Ushakov. Order of Victories are worth the most, but of course you wouldn’t have one, those were only given to generals. But Order of Suvorovs were worth a lot too, he’d pay four hundred fifty dollars for one…. My grandfather walked away then. We walked and walked along Arbat Street in the freezing cold. Then my grandfather couldn’t walk anymore. The sky was almost dark. He sat heavily on the steps of that antiques store and told me to go home without him. The next day, they found him frozen to death there, his hand reaching into his jacket to clench the medal he’d earned with his own blood. His eyes were wide open, looking at the city he’d saved from Guderian’s tanks fifty years ago….”

Marshal Levchenko left the underground war room for the first time in a week. He walked in the thick snowfall, searching for the sun, half set behind the snow-draped pinewoods. In his mind’s eye, he saw a small black dot slowly moving against the orange setting sun: the Vechnyy Buran, with his son inside, farther than any other son from a father.

It had led to many ugly rumors within his homeland, and the enemy utilized it even more fully abroad. The New York Times had printed its headline in black type sized for shock: NO DESERTER HAS RUN FARTHER. Below was a photo of Misha, captioned “At a time when the communist regime is agitating three hundred million Russians for a bloodbath defense against the ‘invaders,’ the son of their marshal has fled the war aboard the nation’s only massive-scale spacecraft. Sixty million miles from the battlefield, he is safer than any other of his fellow citizens.”

But Marshal Levchenko didn’t take it to heart. From secondary school to postgraduate studies, almost none of Misha’s associates had known who his father was. The space program command center made its decision solely because Misha’s field of study happened to be the mathematical modeling of stars. The Vechnyy Buran approaching the sun was a rare opportunity for his research, and the space complex couldn’t be entirely piloted by remote control, requiring at least one person aboard. The general learned of Misha’s background only later, from the Western news media.

On the other hand, whether Marshal Levchenko admitted it or not, deep down inside, he really did hope his son could stay away from the war. It wasn’t solely a matter of blood ties; Marshal Levchenko had always felt that his son wasn’t meant for war—perhaps he was the least meant for war of all the world’s people. But he knew his notion was faulty: was anyone truly meant for war?

Besides, was Misha truly suited for the stars either? He liked stars, had devoted his life to their research, but he himself was the opposite of a star. He was more like Pluto, the silent and cold dwarf planet orbiting in its distant void, out of sight of the mortal realm. Misha was quiet and graceful. Solitude was his nourishment and air.

Misha was born in East Germany, and the day he was born was the darkest day in the marshal’s life. He was only a major that evening in West Berlin, standing guard with his soldiers in front of the Soviet War Memorial in the Tiergarten, keeping vigil for the fallen for the last time in forty years. In front of them were a gaggle of grinning Western officers; and a few slovenly, shiftless German police officers trailing wolfhounds on leashes to replace them; and the skinhead neo-Nazis hollering “Red Army Go Home.” Behind him were the tear-filled eyes of the senior company commander and soldiers. He couldn’t help himself; he, too, let tears blur all this away.

He returned to the emptied barracks after dark. On this last night before he left for home, he was notified that Misha had been born, but that his wife had died of complications from childbirth.

His life after he returned was difficult, too. Like the 400,000 army men and 120,000 administrators withdrawn from Europe, he had no home to go to, and lived with Misha in a temporary shack of metal sheets, freezing in winter and broiling in summer. His old colleagues would do any work for a living, some becoming gun runners for the gangs, some reduced to strip dances at nightclubs. But he stuck to his honest soldier’s life, and Misha quietly grew up amid the hardship. He wasn’t like the other children; he seemed to have been born with an innate ability to endure, because he had a world of his own.

As early as primary school, Misha would quietly spend the entire night alone in his small room. Levchenko had thought he was reading at first, but by chance he discovered that his son was standing in front of the window, unmoving, watching the stars.

“Papa, I like the stars. I want to look at them all my life,” he told his father.

On his eleventh birthday, Misha asked his father for a present for the first time: a telescope. He’d been using Levchenko’s military binoculars to stargaze before then. Afterward, the telescope became Misha’s only companion. He could stand on the balcony and watch the stars until the sky lightened in the east. A few times, father and son stargazed together. The marshal always turned the telescope toward the brightest-looking star, but his son would shake his head disapprovingly. “That one’s not interesting, Papa. That’s Venus. Venus is a planet, but I only like stars.”

Misha didn’t like any of the things that the other kids liked, either. The neighbor’s boy, son of the old paratrooper chief of staff, snuck out his father’s pistol to play with, and ended up shooting his own leg by accident. The general of the staff’s children thought no reward better than their papa taking them to the company firing range and letting them take a shot. But that affinity seemed to have completely skipped over Misha.

Levchenko found his son’s apathy for weapons unsettling, almost intolerable, to the point where he reacted in a way that embarrassed him to think of to this day: Once, he’d quietly set his Makarov semiautomatic on his son’s writing desk. Not long after he returned from school, Misha came out of his room with the pistol. He held it like a child, his hand closed carefully around the barrel. He set the gun gently in front of his father and said, evenly, “Papa, be careful where you put it next time.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hold Up the Sky»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hold Up the Sky» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hold Up the Sky» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.