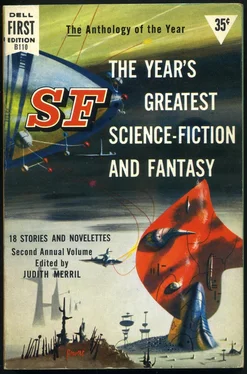

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1957, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1957

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The other paper was of practical value. A certain Julius Marx—again not a medical man, but a design engineer with, apparently, hobbies—had built an electro-encephalograph for two (would anyone ever write a popular song about that?) which graphed each of the patients through a series of stimuli, and at the same time drew a third graph, a resultant.

Marx was after a means of determining brain-wave types, rather than individual specimens, and had done circuitry on machines which would handle up to eight people at once. In a footnote, with dry humor, he had qualified his paper for this particular category: “Perhaps one day the improbable theories of Dr. Prince might approach impossibility through the use of this device upon a case of multiple personality.”

Immediately on reading this, the doctor ordered EEGs on both Anson and Newell, and when he had both before him, he wished fervently that Julius Marx had been there with him; he suspected that the man enjoyed a good laugh, even on himself. The graphs were as different as such graphs can possibly be.

The confirmation of his diagnosis was spectacular, and he left a note for Miss Jarrell to track down every multiple personality case he had rejected for the past eight years and see what could be done about some further tests. What would come after the tests, he did not know—yet.

The other valuable nudge he got from the Marx paper was the idea of a resultant between two dissimilar electro-encephalograms. He made one from the Newell-Anson EEGs —without the use of anything as Goldbergian as Marx’s complicated device, but with a simple computer coupling. He kept it in his top desk drawer, and every few days he would draw it out and he would wonder ...

Therapy for Anson wasn’t therapy. Back at the very beginning, Miss Thomas had said that his was a personality that wouldn’t dismantle; she had been quite right. You can’t get episodic material from an entity which has had no subjective awareness, no experience, which has no name, no sense of identity, no motility, no recall.

There were many parts to that strange radiance of Anson’s and they were all in the eye of the beholder, who protected Anson because he was defenseless, who was continually amazed at his unselfconsciousness as if it were an attribute rather than a lack. His discovery of the details of self and surroundings was a never-ending delight to watch, because he himself was delighted and had never known the cruel penalties we impose on expressed delight, nor the masking idioms we use instead: Not a bad sunset there. Yeah. Real nice.

“He’s good,” Miss Jarrell said to the doctor once. “He’s only good—nothing else.”

Therapy for Newell was, however, therapy, and not rewarding. The properly dismantled and segmented patient is relatively simple to handle.

Key in anger (1200 cycles) and demand “How old are you?” Since anger does not exist unsupported, an episode must emerge; the anger has an object, which existed at a time and place; and there’s your episode. “I’m six,” says your patient. Key in the “You are six years old” note for reinforcement and you’re all ready for significant recall. Or start with the age index: “You are twelve years old.” When that is established, demand, “How do you feel?” and if there is significant material in the twelfth year, it will emerge. If it is fear, add the “fear” note and ask “Where are you?” and you’ll have the whole story.

But not in Newell’s case. There was, of course, plenty of conflict material, but somehow the conflicts seemed secondary; they were effects rather than causes. By far the largest category of traumas is the unjustified attack—a severe beating, a disease, a rejection. It is traumatic because, from the patient’s point of view, it is unjustified. In Newell’s case, there was plenty of suffering, plenty of defeat; yet in every single episode, he had earned it. So he was without guilt. His inner conviction was that his every cruelty was justified.

The doctor had an increasing sense that Newell had lived all his life in a books-balanced, debts-paid condition. His episodes had no continuity, one to the other. It was as if each episode occurred at right angles to the line of his existence; once encountered, it was past, like a mathematical point. The episodes were easy to locate, impossible to relate to one another and to the final product.

The doctor tried hard to treat Anson and Newell in his mind as discrete, totally unconnected individuals, but Miss Jarrell’s sentimental remark kept echoing in his mind: “He’s good; he’s only good—nothing else,” and generating an obverse to apply to Newell: He’s evil, he’s only evil—nothing else.

This infuriated him. How nice, how very nice, he told himself sarcastically, the spirits of good and evil to be joined together to make a whole man, and how tidily everything fits; black is totally black and white is white, and together the twain shall make gray. He found himself telling himself that it wasn’t as simple as that, and things did not work out according to moral evaluations which were more arbitrary even than his assigned audio.

It was about this time that he began to doubt the rightness of his decision, the worth of his therapy, the possibility of the results he wanted, and himself. And he had no one to advise him. He told that to Miss Thomas.

It was easy to do and it surprised both of them. He had called her in to arrange a daily EEG on both facets of the Newell case and explain about the resultant, which he also wanted daily. She said yes, Doctor, and very well, Doctor, and right away, Doctor, and a number of other absolutely correct things. But she didn’t say why, Doctor? or that’s good, Doctor, and suddenly he couldn’t stand it.

He said, “Miss Thomas, we’ve got to bury the hatchet right now. I could be wrong about this case, and if I am, it’s going to be bad. Worse than bad. That’s not what bothers me,” he added quickly, afraid she might interrupt, knowing that this must spill over or never emerge again. “I’ve been through bad things before and I can handle that part of it.”

Then it came out, simple and astonishing to them both: “But I’m all alone with it, Tommie.”

He had never called her that before, not even to himself, and he was overwhelmed with wonderment at where it might have come from.

Miss Thomas said, “No, you’re not,” gruffly.

“Well, hell,” said the doctor, and then got all his control back. He dropped a film cartridge into the viewer and brought out his notes. Using them as index, he sat with his hand on the control, spinning past the more pedestrian material and showing her the highlights. He presented no interpretations while she watched and listened.

She heard Newell snarling, “You better watch what you’re doing,” and Anson pointing about the room, singing, “Floor, flower, book, bed, bubble. Window, wheel, wiggle, wonderful.” (He had not known at that stage what a wonderful was, but Miss Jarrell said it almost every hour on the hour.) She saw Newell in recall, aged eleven, face contorted, raging at his fifth-grade teacher, “I’ll bomb ya, y’ole bitch!” and at thirteen, coolly pleased at something best unmentioned concerning a kitten and a centrifuge.

She saw Anson standing in the middle of the room, left elbow in right hand, left thumb pressed to the point of his chin, a stance affected by the doctor when in perplexity: “When I know everything there is to know,” Anson had said soberly, “there’ll be two Doctor Freds.”

At this, Miss Thomas grunted and said, “You wouldn’t want a higher compliment than that from anybody, anytime.” The doctor shushed her, but kindly. The first time he had seen that sequence, it made his eyes sting. It still did. He said nothing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.