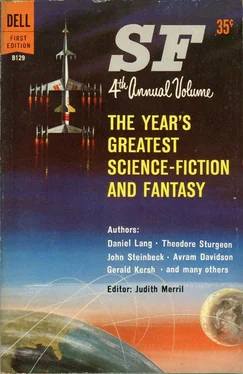

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Richard Gehman is one of America’s most prolific magazine writers, and is an inquisitive and earnest student of our mores, including our fads in jazz and literature.

This story was first published under the by-line, Martin Scott. The name was new to me. I queried editor Ray Russell at Playboy, who wrote to tell me the author’s identity, and also said, “It certainly is an extremely clever piece, but I must admit I don’t see how the satire fits into your book.”

This shook me, because Russell is a type that digs s-f, mostly, and if this is not science fiction, it is what I mean by s-f, and—like, man, I mean, it is the greatest. . . .

It was a season of great restlessness and change for mice everywhere, a stirring time, a time of moods and urges and moves. The mouse felt it; his whiskers trembled in anticipation. One night there was a party in a stall, and an old badger came. He sat there drinking red wine and aspirin gravely, staring at a young and excitable squirrel who had been on cashews for months.

“It’s the time, man!” the squirrel kept saying to the badger, but the mouse knew the message was for him. It had to be for him; the badger had fallen asleep after his third Sneaky Pete. That was the badger’s way of rebellion. No squirrel could bug him.

The mouse got the message. He was quite possibly the hippest mouse that ever crept. He dug. He dug everything —he dug with his sharp little eyes, he dug with his pointy little nose, he dug with his little claws (under each of which he kept a bit of dirt at all times, in case he might be invited to the Actors’ Studio). The mouse dug the gray mice that lived in the universe that was his house, he dug the brown mice that were padded down in the vast unreachable reaches of the fields, and he dug the mice-colored mice that lived nowhere but stayed ever on the road. He even dug rats. Oh, how he dug; he dug the whole world, and he dug his hole-world. He was with it, he was of it, he was in.

This mouse was a cat.

He was well-known, too. He had eaten some pages of verse in some tiny magazines— Trap, Silo Review and Barley —and they had heard of him in San Francisco, where there was a small but pulsating and Mysterious mouse revival swinging. But the season of restlessness caught him and he was hung, and although he had finished chewing three pages of a novel, he said to his mother, “Dad, I got to go.”

There was reason enough: nothing charged him. He’d been on pot. Nothing. He’d gone on pot again; still nothing. He’d then gone on pan, kettle, roaster, colander, soup spoon; he’d tried everything in the kitchen cabinet. No kicks.

The word was out—he’d seen it in the squirrel’s eyes that night at the party. The hipsters had a new kick. Go on clock, the word came. Man, get with the clock-way; man, it’s time; make it man, it’s timeless.

The mouse rushed first to the First National Corn Crib, where all the squares kept their hoards. He started to spit— but he dug it too much, there was too much love in him for squares and everybody else, they were all Zenned up like he was, and he could not do it. He changed his mind, then changed it again. He rushed on. Man, this was living! He rushed over to a haystack where a beetle had a pad and gnawed anarchist poetry. He seized six of the beetle’s legs and shook them violently. The beetle opened three of his four eyes and regarded the mouse with utter serenity. He was stoned, but he had so many eyes he could be stoned and still see everything.

“Come on,” the mouse cried.

The beetle said nothing. That was what was so great about him, the mouse knew; he dug and he never spoke, like the crazy old mixed-up Zenners,

It was time to go again; time to go on time. The mouse ran and ran and ran and ran and finally he was there, at the clock. There it stood, wild as a skyscraper, tall and proud and like all America with a moon-face above it, waving its hands inscrutably and passively, cool as you please. The mouse wished he had a chick to dig it with him but knew that was childish; he was himself, he was with, in, of and it. The realization made his tail twitch. His ears rattled. Then the music came, long and mysterious, like some great old song chanted all the way from Tibet:

Hickory, dickory...

It was the moment of truth: reds and greens and blues crowded in and permeated his little red eyes, he broke out in a cold sweat, he broke in out of a hot sweat.

Dock!

That was it. He ran up, he ran down.

Nothing happened.

Hickory, dickory, dock! the unearthly music came again.

“I dig!” the mouse screamed, and ran up and down again.

“I’m on the clock, Dad!” he cried to no one in particular. Breathless, he shouted it again. A spider, observing him icily from a corner, shrugged and wondered what the younger generation was coming to.

The mouse glanced at the spider. That second was when he knew the truth. Pot was no good, pan was no good, clock was just as bad. There was no escaping it. In the final analysis, he had to look inward. He walked home slowly and chewed up the rest of his novel. Today he is rich, a trustee of the First National Corn Crib, and is thinking of eating another book as soon as he can find the time away from his job. The badger is dead, the beetle has turned chiropractor, and only God digs. Hickory, dickory, dock.

THE YELLOW PILL

by Rog Phillips

“The best laid schemes o’ mice and men,” that Scotsman said, “gang aft a-gley.” Which, in American, means: man or mouse, one can be just as crazy mixed-up as the other.

The late Robert Lindner, in his fascinating The Fifty-Minute Hour, wrote about a patient whose fantasy-world took the form of a space-travel story so credibly constructed that the psychiatrist himself kept drifting into near-acceptance of the reality of the alien planet. Now Mr. Phillips asks: How does the doctor know—for sure—who’s crazy?

Dr. Cedric Elton slipped into his office by the back entrance, shucked off his topcoat and hid it in the small, narrow-doored closet, then picked up the neatly piled patient cards his receptionist Helena Fitzroy had placed on the corner of his desk. There were only four, but there could have been a hundred if he accepted everyone who asked to be his patient, because his successes had more than once been spectacular and his reputation as a psychiatrist had become so great because of this that his name had become synonymous with psychiatry in the public mind.

His eyes flicked over the top card. He frowned, then went to the small square of one-way glass in the reception-room door and looked through it. There were four police officers and a man in a strait jacket.

The card said the man’s name was Gerald Bocek, and that he had shot and killed five people in a supermarket, and had killed one officer and wounded two others before being captured.

Except for the strait jacket, Gerald Bocek did not have the appearance of being dangerous. He was about twenty-five, with brown hair and blue eyes. There were faint wrinkles of habitual good nature about his eyes. Right now he was smiling, relaxed, and idly watching Helena, who was pretending to study various cards in her desk file but was obviously conscious of her audience.

Cedric returned to his desk and sat down. The card for Jerry Bocek said more about the killings. When captured, Bocek insisted that the people he had killed were not people at all, but blue-scaled Venusian lizards who had boarded his spaceship, and that he had only been defending himself.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.