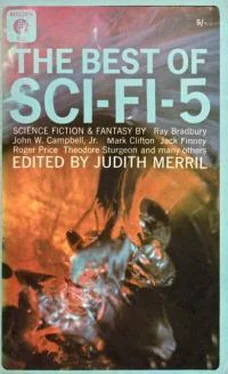

The Best of Sci-Fi-5

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1966, Издательство: Mayflower-Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Best of Sci-Fi-5

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mayflower-Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1966

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Best of Sci-Fi-5: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Best of Sci-Fi-5»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Best of Sci-Fi-5 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Best of Sci-Fi-5», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The corn-knife was not very sharp, but the skin of the sphere parted with disgusting ease. I heard Chris scream, “No! Dad! No!” … but I kept hacking. We were nearly engulfed in the pinkish, albuminous nutritive which gushed from the ruptured sac. I can still smell it.

The creatures inside were more terrible to see in the open air than they had been behind their protective layers of plastic material. They were dead white and they looked to be soft, although they must have had normal human skeletons. Their struggles were blind, pointless and feeble, like those of some kind of larvae found under dead wood, and the largest made a barely audible mewing sound as it groped about in search of what I cannot imagine.

I heard Chris retching violently, but could not tear my attention away from the spectacle. The sphere now looked like some huge coelenterate which had been halved for study in the laboratory, and the hoselike tentacles still moved like groping cilia.

The agony of the creatures in the “grape” (I cannot think of them as People) when they were first exposed to unfiltered, unprocessed air and sunlight, when the wires and tubes were torn from them, and especially when the metal caps on their heads fell off in their panicky struggles and the whole universe of chilly external reality rushed in upon them at once, is beyond my imagining; and perhaps this is merciful. This and the fact that they lay in the stillness of death after only a very few minutes in the open air.

Memory is merciful too in its imperfection. All I remember of our homeward journey is the silence of it.

“Wake up! We have company, old man!”

It is Sue shaking me. Somehow I did sleep—in spite of Chris and in spite of the persistent memory. It must be midmorning. I swing my feet down and scrub at my gritty eyes. Voices outside. Cheerful. How cheerful?

It is Sato and he has his old horse hitched to a crude travois of willow poles. It is Sato and his wife and three kids and my son Chris. There trussed up on the travois is the biggest buck I have seen in ten years, its neck transfixed with an arrow. A perfect shot and one that could not have been scored without the most careful and skillful stalking. I remember teaching him that only a bad hunter … a heedless and cruel one … would risk a distant shot with a bow.

Chris is grinning and looking sheepish. Sato’s daughter is there, which accounts for the look of benign idiocy. I was wondering when he would notice. Then he sees me standing in the door of the cabin and his face takes on about ten years of gravity and thought, but this is not for the benefit of the teen-age female. Little Mike is clawing at Chris and asking why he went away like that and why he went hunting without Daddy, and several other whys which Chris ignores. His answer is for his old man:

“I’m sorry, Dad. I wasn’t mad at you … just sort of crazy. Had to do … this… .” He points at the deer. “Anyhow, I’m back.”

“And I’m glad,” I managed.

“Dad, those elder bushes …”

“To hell with them,” say I. “Wednesday is soon enough.”

Sato moves in grinning, and just in time to relieve the awkwardness. “Dressed out this buck and carried it down the mountain by himself.” I think of mountain lions. “He was about pooped when I found him in a pasture.”

Sue holds open the cabin door and the Satos file in. Himself first, carrying a jug of wine, then Mrs. Sato, grinning greetings. She has never mastered English. It has not been necessary.

I drag up what pass for chairs. Made them myself. We begin talking about weeds and beans, and weather, bugs and the condition of fruit trees. It is Sato who has steered the conversation into these familiar ways, bless his knowing heart. He uncorks the wine. Sue and Mrs. Sato, meanwhile, are carrying on one of their lively conversations. Someday I will listen to them, but I doubt that I will ever learn how they communicate … or what. Women.

I can hear Chris outside talking to Yuki, Sato’s daughter. He is not boasting about the deer; he is telling her about the fight with the tin scorpion and the grape-people.

“Are they blind … the grape-people?” the girl asks.

“Heck no,” says Chris. “At least one of them wasn’t. One of them sicced the robot bug on us. They were going to kill us. And so, Dad did what he had to do… .”

I don’t hear the details over the interjections of Yuki and little Mike, but I can imagine they are as pungent as the teen-age powers of physiological description allow. I hear Yuki exclaim, “Oh how utterly germy!” and another language problem occurs to me. How can kids who have never hung around a drugstore still manage to evolve languages of their own … characteristically adolescent dialects? It is one more mystery which I shall never solve. I hear little Mike asking for reasons and causes with his favorite word. “Why, Chris?”

“I’ll explain it when you get older,” says Chris, and oddly it doesn’t sound ridiculous.

Sato pours a giant-size dollop of wine in each tumbler.

“What’s the occasion?” I ask.

Sato studies the wine critically, holding the glass so the light from the door shines through.

“It’s Tuesday,” he says.

THE MAN WHO LOST THE SEA

by Theodore Sturgeon

from “The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction: Series Nine” (Doubleday, 1960)

“… But science,” they’re still telling us, “has caught up with science fiction….” Or: “What are you guys gonna write about now you got space flight?”

Obviously, not about space flight. Not one of the eighteen selections preceding this has been concerned with rocketry or astrogation or planet-hopping, except as an occasional incidental background touch.

Science—at least nuclear physics and space-flight technology—have caught up with us enough so that the speculative gleanings in these fields are sparse indeed. We are migrating to the less well-harvested neo-scientific fertile acreage of the “humanic studies.”

I say, “migrate,” and I do mean like a flock of birds. Thing now is to figure out whether Solo Sturgeon stayed behind on this one—or went way out, reconnoitering the next flight.

The sick man is buried in the cold sand with only his head and his left arm showing. He is dressed in a pressure suit and looks like a man from Mars. Built into his left sleeve is a combination time-piece and pressure gauge, the gauge with a luminous blue indicator which makes no sense, the clock hands luminous red. He can hear the pounding of surf and the soft swift pulse of his pumps. One time long ago when he was swimming he went too deep and stayed down too long and came up too fast, and when he came to it was like this: they said, “Don’t move, boy. You’ve got the bends. Don’t even try to move.” He had tried anyway. It hurt. So now, this time, he lies in the sand without moving, without trying.

His head isn’t working right. But he knows clearly that it isn’t working right, which is a strange thing that happens to people in shock sometimes. Say you were that kid, you could say how it was, because once you woke up lying in the gym office in high school and asked what had happened. They explained how you tried something on the parallel bars and fell on your head. You understood exactly, though you couldn’t remember falling. Then a minute later you asked again what had happened and they told you. You understood it. And a minute later…forty-one times they told you, and you understood. It was just that no matter how many times they pushed it into your head, it wouldn’t stick there; but all the while you knew that your head would start working again in time. And in time it did…. Of course, if you were that kid, always explaining things to people and to yourself, you wouldn’t want to bother the sick man with it now.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Best of Sci-Fi-5»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.