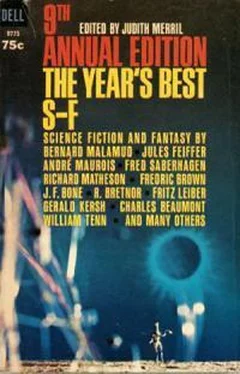

The Year's Best Science Fiction 9

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Year's Best Science Fiction 9» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1965, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Best Science Fiction 9

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1965

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Best Science Fiction 9: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Best Science Fiction 9»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Best Science Fiction 9 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Best Science Fiction 9», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“What are you talking about?” asked the Lord Starmount.

“What I found in space 3,” snapped Artyr Rambo. “Believe it or not. This is what I now remember. Maybe it’s a dream, but it’s all I have. It was years and years and it was the blink of an eye. I dreamed green nights. I felt places where the whole horizon became one big waterfall. The boat that was me met children and I showed them El Dorado, where the gold men live. The people drowned in space washed gently past me. I was a boat where all the lost spaceships lay drowned and still. Seahorses which were not real ran beside me. The summer month came and hammered down the sun. I went past archipelagoes of stars, where the delirious skies opened up for wanderers. I cried for me. I wept for man. I wanted to be the drunkboat sinking. I sank. I fell. It seemed to me that the grass was a lake, where a sad child, on hands and knees, sailed a toy boat as fragile as a butterfly in spring. I can’t forget the pride of unremembered flags, the arrogance of prisons which I suspected, the swimming of the businessmen! Then I was on the grass.”

“This may have scientific value,” said the Lord Starmount, “but it is not of judicial importance. Do you have any comment on what you did during the battle in the hospital?”

Rambo was quick and looked sane: “What I did, I did not do. What I did not do, I cannot tell. Let me go, because I am tired of you and space, big men and big things. Let me sleep and let me get well.”

Starmount lifted his hand for silence.

The panel members stared at him.

Only the few telepaths present knew that they had all said, “ Aye. Let the man go. Let the girl go. Let the doctors go . But bring back the Lord Crudelta later on. He has many troubles ahead of him, and we wish to add to them.”

Between the Instrumentality, the Manhome Government and the authorities at the Old Main Hospital, everyone wished to give Rambo and Elizabeth happiness.

As Rambo got well, much of his Earth Four memory returned. The trip faded from his mind.

When he came to know Elizabeth, he hated the girl.

This was not his girl - his bold, saucy, Elizabeth of the markets and the valleys, of the snowy hills and the long boat rides. This was somebody meek, sweet, sad and hopelessly loving.

Vomact cured that.

He sent Rambo to the Pleasure City of the Herperides, where bold and talkative women pursued him because he was rich and famous.

In a few weeks - a very few indeed-he wanted his Elizabeth, this strange shy girl who had been cooked back from the dead while he rode space with his own fragile bones.

“Tell the truth, darling.” He spoke to her once gravely and seriously. “The Lord Crudelta did not arrange the accident which killed you?”

“They say he wasn’t there,” said Elizabeth. “They say it was an actual accident. I don’t know. I will never know.”

“It doesn’t matter now,” said Rambo. “Crudelta’s off among the stars, looking for trouble and finding it. We have our bungalow, and our waterfall, and each other.”

“Yes, my darling,” she said, “each other. And no fantastic Floridas for us.”

He blinked at this reference to the past, but he said nothing. A man who has been through space 3needs very little in life, outside of not going back to space 3. Sometimes he dreamed he was the rocket again, the old rocket taking off on an impossible trip. Let other men follow! he thought. Let other men go! I have Elizabeth and I am here.

SUMMATION: SF, 1963

by Judith Merril

Never before have so many been threatened with so much.

If the fallout doesn’t get you, the fault slip will. The next ice age, we are shiveringly reminded, is practically upon us. It may be a matter of only thousands, or hundreds, of generations before our sun goes nova. And if neither natural nor man-made Doomsday befall us, it will be not hundreds, but ten or less generations before we must cope with the prospects of starvation—or suffocation—in the foul-aired plankton-fed single supermegapolis of Earth’s sardine-can-packed population.

It is not that the dangers are new: just that we are newly aware of them.

Never has so much been promised to so many.

The wealth of our technological civilization, today, is beyond the wildest fantasies of earlier times: wealth measured not in such abstractions as “capital goods” or “national incomes,” but in the actualities of physical comfort, health, leisure, longevity, and even that most vital (and most alienable) of “natural rights,” the freedom-and-capacity to pursue individual happiness.

That wealth, like technology, is unevenly distributed, we know. But even the most horrifying (to us) conditions of life on Earth today were only the norm for the human condition until a few scant centuries ago. (Neither Plato nor Lao-tse would have paused long in their dialogues on politics or morality, to be shocked at the deaths of four children in a rebellion-quelling like Birmingham’s bombing. Apartheid standards of living would have seemed slave-coddling to Cheops or Genghis Khan. The civil rights available to a Red Chinese peasant today would have dazzled a serf in the kitchens of Louis XIV of France.) And the increment in knowledge and productivity continues to accelerate while it spreads. The real-wealth potential is constantly greater both in total quantity and in wide availability.

The resources of our world are not new; we have just started to make use of them.

Never has so much uncertainty been felt by so many.

In our relations with the physical environment, we first learned simple skills to use it, then acquired some understanding of it) only then could we start to remake it to our advantage. The accumulation of observations by countless naturalists and discoverers provided a basis for analytical science; the scientist’s hypothesis-and-experiment is the base on which the inventor and engineer stand.

As far back as any history goes, human beings have observed each other; primitive techniques for controlling and utilizing human intelligence and personality were discovered in the age of myths. But the first systematic, analytic, scientific studies of mankind by man began barely a century ago—five hundred years behind physical science. If the rate of progress has been swifter, it is because we had already learned something of the techniques of scientific investigation, and because we now have the products of earlier sciences to use as tools and mirrors for self-study. (Electroencephalography probes and measures the functions of the brain; a cybernetic machine mirrors it.)

We are now rapidly approaching the kind of understanding of our own thoughts, emotions, capacities, and behavior which will, abruptly (next year? next decade?), break through to the level of application and invention. The true science of humanics, when it emerges, will of necessity convey the power to remake our intellects and personalities to our advantage... or lo our final doom.

The concept of self-determination is not new; but we are now about to acquire the capacity for it.

Science fantasy is not so new now either; it has apparently just, reached the level of self-consciousness. That is: never before has so much been published by or about writers and writing of speculative fiction.

There was the usual scattering of individual items:

Fredric Brown had a page of poetic definition in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Isaac Asimov had two pages in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, urging the use of an early taste for good science fiction as a selection test for creative scientific potential more effective than any combination of intelligence, aptitude, and personality tests now in use in our schools.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction 9»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction 9» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Best Science Fiction 9» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.