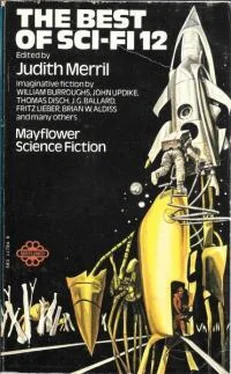

The Best of Science Fiction 12

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Best of Science Fiction 12» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1970, ISBN: 1970, Издательство: Mayflower, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Best of Science Fiction 12

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mayflower

- Жанр:

- Год:1970

- ISBN:0583117848

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Best of Science Fiction 12: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Best of Science Fiction 12»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Best of Science Fiction 12 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Best of Science Fiction 12», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Feeling my stomach clench itself painfully, I ran behind Selina to the side of the cottage. Beyond the window the neat living room, with its coal fire, was empty but the child's toys were scattered on the floor. Alphabet blocks and a wheelbarrow the exact colour of freshly pared carrots. As I stared in, the boy came running from the other room and began kicking the blocks. He didn't notice me. A few moments later the young woman entered the room and lifted him, laughing easily and wholeheartedly as she swung the boy under her arm. She came to the window as she had done earlier. I smiled self-consciously, but neither she nor the child responded.

My forehead prickled icily. Could they both be blind? I sidled away.

Selina gave a little scream and I spun towards her.

"The rug!" she said. "It's getting soaked."

She ran across the yard in the rain, snatched the reddish square from the dappling wall and ran back, towards the cottage door. Something heaved convulsively in my subconscious.

"Selina," I shouted. "Don't open it!"

But I was too late. She had pushed open the latched wooden door and was standing, hand over mouth, looking into the cottage. I moved close to her and took the rug from her unresisting fingers.

As I was closing the door I left my eyes traverse the cottage's interior. The neat living room in which I had just seen the woman and child was, in reality, a sickening clutter of shabby furniture, old newspapers, cast-off clothing and smeared dishes. It was damp, stinking and utterly deserted. The only object I recognised from my view through the windows was the little wheelbarrow, paintless and broken.

I latched the door firmly and ordered myself to forget what I had seen. Some men who live alone are good housekeepers; others just don't know how.

Selina's face was white. "I don't understand. I don't understand it"

"Slow glass works both ways," I said gently. "Light passes out of a house, as well as in."

"You mean ... ?"

"I don't know. It isn't our business. Now steady up — Hagan's coming back with our glass." The churning in my stomach was beginning to subside.

Hagan came into the yard carrying an oblong, plastic-covered frame. I held the cheque out to him, but he was staring at Selina's face. He seemed to know immediately that our uncomprehending fingers had rummaged through his soul. Selina avoided his gaze. She was old and ill-looking, and her eyes stared determinedly towards the nearing horizon.

"I'll take the rug from you, Mr. Garland," Hagan finally said. "You shouldn't have troubled yourself over it."

"No trouble. Here's the cheque."

"Thank you." He was still looking at Selina with a strange kind of suspicion. "It's been a pleasure to do business with you."

"The pleasure was mine," I said with equal, senseless formality. I picked up the heavy frame and guided Selina towards the path which led to the road. Just as we reached the head of the now slippery steps Hagan spoke again.

"Mr. Garland!"

I turned unwillingly.

"It wasn't my fault," he said steadily. "A hit-and-run driver got them both, down on the Oban road six years ago. My boy was only seven when it happened. I'm entitled to keep some thing."

I nodded wordlessly and moved down the path, holding my wife close to me, treasuring the feel of her arms locked around me At the bend I looked back through the rain and saw Hagan sitting with squared shoulders on the wall where we had first seen him.

He was looking at the house, but I was unable to tell if there was anyone at the window.

Take a word, a multiplex word: science-fiction.

In Popland, it's camp comics; for Sontag, horror films; UFO people claim it as kissing kin; news-media editorialists equate it generally with disquieting technological prediction. On TV it's space-geared Western or Tropic Isle adventure — or Spy Thrillers with aliens, robots or a mad scientist as The Enemy. Paperback buyers grab up two books a week of the TV type, and probably half again as much E. R. Burroughs-derived 'sword and sorcery' and 'Heroic fantasy'. Some paperbacks, and a few hardcovers, have made it into the 'underground' (campus and hippie trade), a very mixed bag where the Hobbits and Ubu rub elbows with Witzend, Nova Express, and Stranger in a Strange Land — and with two-dollar soft-covers of Hawthorne, Lovecraft, and Mary Shelley for the Lit Profs who have decided (with the help of H. Bruce Franklin's Future Perfect, Oxford, 1966) that science fiction is really Neo-Victorian-Gothic.

For some faithful 50,000 fans, science fiction is (inclusively and almost exclusively) any thing published in the speciality magazines — where in fact there is rarely more than one story per issue (if that) which meets the requirements of that esoteric modern form, science fiction. For within the wide spread of contemporary 'nonrealstic' prose, there does remain a discrete discipline — 'hard-core science fiction' — with specialised, and rather demanding, parameters. It is no easier to define now than it was in the days of its glory, but it is readily recognisable — and dearly beloved — by those who, like myself, have identified most of their adult intellectual lives with it . Vide: 'Light of Other Days'.

It is not so easy to classify 'Beyond the Weeds'. Like Shaw, Peter Tate is a newspaperman: sub-editor of the Echo in South Wales (also not-quite-British?). Both men are in their thirties. Tate perhaps five years the younger. But where Shaw — in style, content, publishing history — is typical of the best of the first generation of British s-f writers, Tate is almost the prototype of the young New Worlds writer: five of his first seven stories were in NW in 1966-67; but more to the point was his reply to my selection of 'The PostMortem People' (form NW) — this retitled and extensively rewritten version of a story already two years old, and hardly satisfactory, to a growing writer. His first novel, The Thinking Seat, will be published by Doubleday in 1968.

Beyond the Weeds

Peter Tate

This time, Anton Hejar came by chance upon the event. He heard the shrill gathering of locked tires and was running before any sick-soft sound of impact. The car could be skidding, no more; but one could not afford to stand and wait. One had a reputation.

He shouldered a passage through the lazy-liners on the rotor walk even as a bundle with flapping limbs and thrown-back head turned spit-wise in the air. He was at curbside when the body landed close to his feet.

Hejar placed his overcoat gently to retain a little of the man's draining warmth.

"Somebody get an ambulance," he shouted, taking command of the situation while women grew pale and lazies changed to the brisker track and were borne smartly away.

The man's eyes flickered. A weak tongue licked vainly at lips grown dry as old parchment. Breath came like a flutter of moth's wings.

"How are you feeling?" asked Hejar.

The eyes searched for the speaker, blinked and blinked again to bring him into focus. The man tried to speak, but there was only a rattle like too many unsaid words fighting for an outlet.

Hejar sniffed the air. His nostrils, finely attuned to the necessities of his calling, could pick out death like hollyhock or new-made bread. Yes, it was there, dank and acrid as stale perspiration.

"No need to worry," he told the man. "You'll be all right."

He took off his jacket to make a pillow for the man's head.

"My ... wife ... she ... "

"Don't concern yourself," said Hejar. "Let's get you settled first."

He's kind, thought the man in his mind full of moist pain. Perhaps he just isn't trying to fool me with sentimentality. I feel so cold ...

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Best of Science Fiction 12»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Best of Science Fiction 12» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Best of Science Fiction 12» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.