“Someone’s coming,” said Alyx.

“Don’t care.” This was Edarra on the deck, muffled. Alyx reached out and began to stroke the girl’s disordered hair, braiding it with her fingers, twisting it round her wrist and slipping her hand through it and out again.

“Someone’s in a fishing smack coming this way,” said Alyx.

Edarra burst into tears.

“Now, now, now!” said Alyx, “why that? Come!” and she tried to lift the girl up, but Edarra held stubbornly to the deck.

“What’s the matter?” said Alyx.

“You!” cried Edarra, bouncing bolt upright. “You; you treat me like a baby.”

“You are a baby,” said Alyx.

“How’m I ever going to stop if you treat me like one?” shouted the girl. Alyx got up and padded over to her new clothes, her face thoughtful. She slipped into a sleeveless black shift and belted it; it came to just above the knee. Then she took a comb from the pocket and began to comb out her straight, silky black hair. “I was remembering,” she said.

“What?” said Edarra.

“Things.”

“Don’t make fun of me.” Alyx stood for a moment, one blue-green earring on her ear and the other in her fingers. She smiled at the innocence of this red-headed daughter of the wickedest city on earth; she saw her own youth over again (though she had been unnaturally knowing almost from birth), and so she smiled, with rare sweetness.

“I’ll tell you,” she whispered conspiratorially, dropping to her knees beside Edarra, “I was remembering a man.”

“Oh!” said Edarra.

“I remembered,” said Alyx, “one week in spring when the night sky above Ourdh was hung as brilliantly with stars as the jewelers’ trays on the Street of a Thousand Follies. Ah! what a man. A big Northman with hair like yours and a gold-red beard-God, what a beard! — Fafnir — no, Fafh — well, something ridiculous. But he was far from ridiculous. He was amazing.”

Edarra said nothing, rapt.

“He was strong,” said Alyx, laughing, “and hairy, beautifully hairy. And willful! I said to him, ‘Man, if you must follow your eyes into every whorehouse—’ And we fought! At a place called the Silver Fish. Overturned tables. What a fuss! And a week later,” (she shrugged ruefully) “gone. There it is. And I can’t even remember his name.”

“Is that sad?” said Edarra.

“I don’t think so,” said Alyx. “After all, I remember his beard,” and she smiled wickedly. “There’s a man in that boat,” she said, “and that boat comes from a fishing village of maybe ten, maybe twelve families. That symbol painted on the side of the boat — I can make it out; perhaps you can’t; it’s a red cross on a blue circle — indicates a single man. Now the chances of there being two single men between the ages of eighteen and forty in a village of twelve families is not—”

“A man!” exploded Edarra. “That’s why you’re primping like a hen. Can I wear your clothes? Mine are full of salt,” and she buried herself in the piled wearables on deck, humming, dragged out a brush and began to brush her hair. She lay flat on her stomach, catching her underlip between her teeth, saying over and over “Oh— oh — oh—”

“Look here,” said Alyx, back at the rudder, “before you get too free, let me tell you: there are rules.”

“I’m going to wear this white thing,” said Edarra busily.

“Married men are not considered proper. It’s too acquisitive. If I know you, you’ll want to get married inside three weeks, but you must remember—”

“My shoes don’t fit!” wailed Edarra, hopping about with one shoe on and one off.

“Horrid,” said Alyx briefly.

“My feet have gotten bigger,” said Edarra, plumping down beside her. “Do you think they spread when I go barefoot? Do you think that’s ladylike? Do you think—”

“For the sake of peace, be quiet!” said Alyx. Her whole attention was taken up by what was far off on the sea; she nudged Edarra and the girl sat still, only emitting little explosions of breath as she tried to fit her feet into her old shoes. At last she gave up and sat — quite motionless — with her hands in her lap.

“There’s only one man there,” said Alyx.

“He’s probably too young for you.” (Alyx’s mouth twitched.)

“Well?” added Edarra plaintively.

“Well what?”

“Well,” said Edarra, embarrassed, “I hope you don’t mind.”

“Oh! I don’t mind,” said Alyx.

“I suppose,” said Edarra helpfully, “that it’ll be dull for you, won’t it?”

“I can find some old grandfather,” said Alyx.

Edarra blushed.

“And I can always cook,” added the pick-lock.

“You must be a good cook.”

“I am.”

“That’s nice. You remind me of. a cat we once had, a very fierce, black, female cat who was a very good mother,” (she choked and continued hurriedly) “she was a ripping fighter, too, and we just couldn’t keep her in the house whenever she — uh—”

“Yes?” said Alyx.

“Wanted to get out,” said Edarra feebly. She giggled. “And she always came back pr — I mean—”

“Yes?”

“She was a popular cat.”

“Ah,” said Alyx, “but old, no doubt.”

“Yes,” said Edarra unhappily. “Look here,” she added quickly, “I hope you understand that I like you and I esteem you and it’s not that I want to cut you out, but I am younger and you can’t expect—” Alyx raised one hand. She was laughing. Her hair blew about her face like a skein of black silk. Her gray eyes glowed.

“Great are the ways of Yp,” she said, “and some men prefer the ways of experience. Very odd of them, no doubt, but lucky for some of us. I have been told — but never mind. Infatuated men are bad judges. Besides, maid, if you look out across the water you will see a ship much closer than it was before, and in that ship a young man. Such is life. But if you look more carefully and shade your red, red brows, you will perceive—” and here she poked Edarra with her toe—“that surprise and mercy share the world between them. Yp is generous.” She tweaked Edarra by the nose.

“Praise God, maid, there be two of them!”

So they waved, Edarra scarcely restraining herself from jumping into the sea and swimming to the other craft, Alyx with full sweeps of the arm, standing both at the stem of their stolen fishing boat on that late summer’s morning while the fishermen in the other boat wondered— and disbelieved — and then believed — while behind all rose the green land in the distance and the sky was blue as blue. Perhaps it was the thought of her fifteen hundred ounces of gold stowed belowdecks, or perhaps it was an intimation of the extraordinary future, or perhaps it was only her own queer nature, but in the sunlight Alyx’s eyes had a strange look, like those of Loh, the first woman, who had kept her own counsel at the very moment of creation, only looking about her with an immediate, intense, serpentine curiosity, already planning secret plans and guessing at who knows what ungues sable mysteries. .

(“You old villain!” whispered Edarra, “we made it!”) But that’s another story.

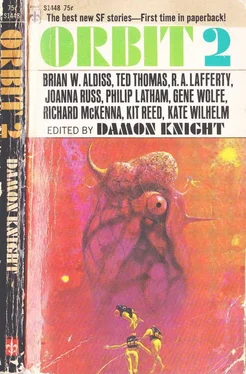

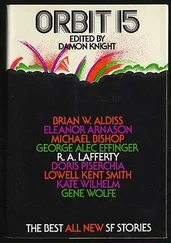

R. A. Lafferty, the author of this magnificently loony story, is a 51-year-old bachelor, an ex-drinker, a sports fan, and a collector of languages. Self-taught (except for an International Correspondence Schools degree in electrical engineering), he has a reading knowledge of all the languages of the Latin, German and Slavic families, as well as Gaelic and Greek. The Army sent him to Morotai (Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia), New Guinea and the Philippines, and at one time he could speak pretty good Passar Malay and Tagalog. He turned to writing, about six years ago, as a substitute for serious drinking. The tavernkeepers weep while we rejoice: Lafferty's stories are full of a warm Bacchic glow, recollected in sobriety — euphoria, comradeship, nostalgia, and the ever-renewed belief that something wonderful may happen.

Читать дальше