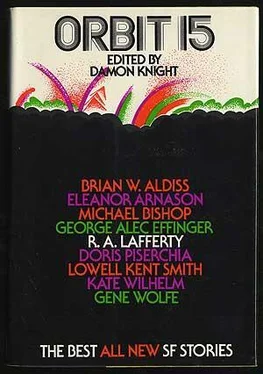

Damon Knight - Orbit 15

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 15» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 15

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- ISBN:0-06-012439-3

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 15: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 15»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 15 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 15», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She gave her folk break-bone bread, and maid bread, and giant bread, and love loaf. She gave them wasp honey and hornet honey. She gave them blood pudding and offal (“Love each other and eat offal” was one of her high mottos) and bad wine. A visitor in Amor Town that year (there was no such town in any other year) reported that most of the courtiers did know the difference between good wine and bad wine, and that they preferred the bad. Joan gave her people sulfur for condiment, salt being forbidden to them. She gave them heifer milk.

And Joan provided her people with hemp and with hoppy-poppy, with gobbling mushrooms and with ragged dream-weeds, with all the unreality seeds and substances and oils, with the aromatic and reason-wrenching plant known as smoke-poke the anti-incense; and the anti-incense raised its smoke not to heaven but to the low sky. These things were dispensed in that part of Joan’s court known as the Ships of Tarshish.

The visitor to Amor, the one just mentioned, had asked several of the courtiers, “Do any of you know of any giant nearby who has disappeared or been slaughtered?” “Yes, there was one,” the courtiers told him. “Our Papess Joan had him blown up with the new blowup powder from China. There may have been others, but now there will be no more giants. Pieces of them will smash down from the low sky whenever the weather is right. These are what we call giant bread.”

So the courtiers had plenty to eat and drink and smoke and inject. They had more than enough, for they finished nothing at all. They were grinning, nervous, ecstatic, jerky courtiers, robust of ear, but somewhat deficient in all other parts.

The city of Amor was built lightly, loosely, insubstantially, unpattemed and unstructured. It had solved the cursed necessity of having buildings and such materialities, for its buildings were very short on material. They were false-front and false-middle erections. The buildings were built of cardboard.

(“But they didn’t have cardboard then,” the avid annalist said. Had they not? Disputed years are not in sequence. They have what they have. But no, the annalist was correct. They didn’t have cardboard in Amor.)

The buildings, the whole town, was built of bark and willow withies. They were tricky, and they were almost grand. It was an architecture almost without weight. White and gray clay was smeared on the bark, and behold! there was the appearance of regal marble. All were gilt with fool’s gold in whorled design, and at the same time all were in motley. Yes, the buildings, the buildings were in clown-suit getup of all light colors, with their own rakish royalty about them, and their precociousness. There was no maturity about them: they did not desire maturity. And at the same time there was nothing of the childlike: they sure did not desire children. There was the taut interruption, the jerk back from the momentous. (“That no thing come to term!” was another of the high Amor mottos.)

And many of the buildings were no more than burlap cloth new out of China (so many things were new out of China, the feeble tea, the sleepy poppy, the tuneless music, the lack of giants) and tent poles. But these buildings showed their own solidity without weight (the sleepy poppy was partly responsible for their showing of solidity), and their own dazzle. In the presence of this dazzle, burlap is almost sunshine-color, it is almost gold, almost yellow, almost rich brown; and it is made out of the holy hemp and the unholy jape-jute.

These near-weightless buildings were peculiar in their horned domes, in their toadstool towers, in their lacelike pillars. Burlap shapes much more easily than stone, though its strength is less. The buildings would have blown down in a good wind, but for the long, disputed year there was no wind at all, no hint of a storm, not even a breeze.

It’s true that in one region there was a semblance of a breeze now and then, and little bells (like sheep bells or goat bells) seemed to tinkle in this breeze. But it was all masquerade. Close examination would have shown that each bell was shaken by a small worm to cause the tinkling. They were woolly worms, caterpillars really. And a very close examination would have revealed that each of these caterpillars had its head notched in an inhibiting incision: the thing would never come to term; it would never be more than a caterpillar.

And also there was something wrong with the tinkling of the small bells. Fine examination would have shown that each of them was cracked, as was their sound. In this region also there were trees with leaves too green, and meadow flowers with blooms too yellow and too red. There was sodded grass that was not true grass. There was a rank goatishness over everything, but it was not the whiff of honest goat. This false breeze and false greenery were in the region of the court that was called the Groves of Arcady.

St. Peter’s looked distorted and deformed. But St. Peter’s was not built yet? It may not have been, as you know it; but it was built of bark and burlap and lashed poles. It was a burlesque of what it later became. There is no law that a burlesque of a thing may not appear before the thing itself.

The afore-cited traveler to Amor in the disputed year has written that the tongue of the people was langue d’oc and that the ears of the people were asses’ ears. Others have said that the ears more resembled goats’ ears. The people could waggle their strange ears, and many had painted them motley colors, one yellow and one red. But there was nothing artificial about the strangely mutated ears. They were well rooted, and they were robust, the only robust things about those folk. And they had to be. The noise there was loud. Even the great mutated ears often bled bright red blood from the overpowering sound. And the sense of balance which lives in the inner ear was often destroyed. This accounts for much of the eccentricity of the chorea or St. Vitus dancers. They were the wobblies. The shattered and shattering noises also deformed other wavicles: those of light (for they made all colors into a crooked dazzle, and they manufactured colors where there could not be colors); the olfactory wavicles, so that the cloying bloodiness of giant bread, the sky-scorching feather smell of flaming ducks or quail, the burning pine knots of the steamboats, the rotten-roses floweriness of the court were all blended into a tall symphony of smell; the radio wavicles that mutated till they brought programs from the distant past (“This is station alex, Alexandria, Egypt, bringing you the Year One Wonders”) and from the distant future (“Station kvoo, Bristow, Oklahoma, bringing a program sponsored by Johnny Horany the Hamburger King”). But it was the sound wavicles that predominated, that had made the ears become the highlights of the heads.

There was amplification for the electrical guitars and other instruments. This amplification had been made possible by the insoluble genius of Sparky McCarky. That wandering man, the Unholy Fool of the Hebrides, had brought, in jugs, from his native Benbecula Island, a quantity of the spectacular lightning that nests in the crags there. He had brought this jugged lightning to Amor Town; he had installed plug-ins where it might be tapped, and so his lightning had been turned into amplified sound.

The music and the lyrics weren’t much. One couldn’t hear them for the sound. There was a sort of projection in midair of the musical scores and the words of the lyrics. Some say that they were projected as on a visual screen; others say that it was a multi-media screen. Some of those poets weren’t bad. Dante was there for part of the year. Others of the great ones were there for a while, but finally the bad poets drove out the good ones.

In one central part of Amor Town, the sound reached such a strength that it sustained itself thereafter. When hands were removed from the instruments, the instruments still dinned on. When singers left, their voices remained. There was no stopping them. And when, beyond this noisy centrality, in the other fun spots—(The Gory Ox, The Calamity Howl, The Whoop Coop, The Gayety Gate (where Gayety Unrestrained sang with her sinewy voice)—the sound died away during the rare sleeping hours, that sound could be “lighted” again at the great, self-sustaining noise center, and it could be carried on a vibrating string to any of those bistros, there to rekindle the dead sound.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 15»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 15» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 15» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.