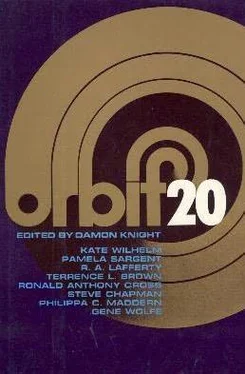

Damon Knight - Orbit 20

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 20» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1978, ISBN: 1978, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 20

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1978

- ISBN:0-06-012429-6

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 20: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 20»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 20 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 20», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I worked at least a month, maybe more, before I had a draft to show Karath. Oddly enough, I could not sustain my anger at him nor my grief at Reina’s departure. I understood what had happened and what I had felt, but these events and feelings were simply material to be shaped and structured.

I gave my final draft to the servo and waited. At last the door opened. I made my way downstairs to Karath’s study.

He sat behind his desk perusing my novella. I cleared my throat. His cold eyes surveyed me as he said, “It isn’t bad, Dorenmatté. It wouldn’t make it in a race, but there might be some hope for you.” As I basked in this high praise, he threw the manuscript at me. “Now go back to work and clean up some of your sentences.”

A year later I took the gold medal in the PanAmerican Games.

But it was Olympic gold I wanted, the high point for a champion. There would be publicity, perhaps other competitions if my health held out. But contests were for the young. Eventually I would become a trainer or sign contracts with the entertainment industry; gold-medal winners can get a lot for senso plots or dream construction. Maybe novelists can do serialized week-long dreams and short-story writers are better at commercials, but you can’t beat a novella writer for an evening’s sustained entertainment. Since practically no one reads now, except of course the critics, most of them failed writers who write comments on our work for each other and serve as judges during competitions, there isn’t much else a champion can do when the contest years are over.

The Olympics! Karath rode us mercilessly in preparation for them. He presented countless distractions: robots outside with jackhammers, emotional crises, dirty tricks meant to disorient us, impossible deadlines.

Two years before the Games, which like the ancient Olympics are held only every four years, I had to enter preliminaries. I got through them easily. The night before I left for Rome, Karath and the others workshopped a story of mine and tore it to shreds. I recall the hatred I saw in the faces of my fellow trainees. None had qualified this time, although all had won locals or regionals. They would undoubtedly gossip maliciously about me when I left and point out to each other how inferior my work really was.

I arrived in Rome the day before the opening ceremonies. The part of the Olympic Village set aside for writers was a scenic spot. The small stone houses were surrounded on three sides by flower gardens and wooded areas. Below us lay all of Rome; the dome of St. Peter’s, the crowded streets, the teeming arcologies. I wanted to explore it all, but I had to start sizing up the competition.

I sought out Jules Pepperman, who had been assigned a house near mine. I had met him at the PanAmerican Games. Jules was tied into the grapevine and always volunteered information readily.

He was a tall slender fellow with an open, friendly personality and a habit of trying to write excessively ambitious works during competition, a practice I regarded as courting disaster. It had messed him up before, but it had also won him a gold in the Anglo-American Games and a silver in the PEN Stakes. I couldn’t afford to ignore him.

His house smelled of herb tea and patent medicines. Jules had arrived with every medication the judges would allow. I wondered how he endured competition, with his migraines and stomach ailments. But endure it he did, while complaining loudly about his health to everyone.

I sat in his kitchen while he poured tea. “Did you hear, Alena? I’m ready to go home, I’m sick of working all the time, the prelims almost wiped me out. There’s this migraine I can’t get rid of and the judges won’t let me take the only thing that helps. And when I heard . . . you want honey in that?”

“Sure.” He dropped a dollop in my tea. “What did you hear?”

“Ansoni. He’s so brilliant and I’m so dumb. I can’t take any more.”

“What about Ansoni?”

“He’s here. He’s competing. Haven’t you heard? You must have been living in a cave. He’s competing. In novella.”

“Shit,” I said. “What’s the matter with him? He must be almost sixty. Isn’t he ineligible?”

“No. Don’t you keep up with anything? He never worked professionally and he wasn’t a trainer.”

I tried to digest this unsavory morsel. I hadn’t even known that Michael Ansoni was still among the living. He had taken a gold medal in short-story competition long ago and gone on to win a gold eight years later in novella, the only writer to change categories successfully. I couldn’t even remember all his other awards.

“I can’t beat him,” Jules wailed. “I should have been a programmer. All that work to get here, and now this.”

I had to calm Jules down. I didn’t like his writing, which was a bit dense for my taste, but I liked him. “Listen,” I said, “An-soni’s old. He might fold up at his age. Maybe he’ll die and be disqualified.”

“Don’t say that.”

“I wouldn’t be sorry. Well, maybe I would. Who else looks good?”

“Nionus Gorff.” Gorff was always masked; no one had ever seen his face. He had quite a cultish following.

“Naah,” I responded. “Gorffhates publicity too much, he’ll be miserable in a big race like this.”

“There’s Jan Wolowski. But I don’t think he can beat Ansoni.”

“Wolowski’s too heavyhanded. He might as well do propaganda.”

“There’s Arnold Dankmeyer.”

I was worried about Dankmeyer myself. He was popular with the judges, although that might not mean much, APOLLO, the Olympic computer, actually picked the winners, but the judges’ assessments were fed in and considered in the final decisions. No one could be sure how much weight they carried. And Dankmeyer was appealingly facile. But he was often distracted by his admirers, who followed him everywhere and even lived in his house during races. He might fold.

“Anyway,” I said, “you can’t worry about it now.” I was a bit insulted that Jules wasn’t worried about me.

“I know. But the judges don’t like me, they never have.”

“Well, they don’t like me either.” I had, in accordance with Karath’s advice, cultivated a public image with which to impress the judges. My stock-in-trade was unobtrusiveness and selfdoubt. I would have preferred being a colorful character like Karath, but I could never have carried that off. Being quiet might not win many points, but there was always a chance the judges would react unfavorably to histrionics and give points to a shy writer.

“At least they don’t hate you,” Jules mumbled. “I need a vacation. I can’t take it.”

“You’re a champion, act like one,” I said loftily. I got up and made my departure, wanting to rest up for the opening ceremonies.

We looked terrific in the stadium, holding our quill pens, clothed in azure jumpsuits with the flags of our countries over our chests. The only ones who looked better were the astrophysicists, who wore black silk jumpsuits studded with rhinestone constellations. They were only there for the opening ceremonies; their contests would be held on the Moon. At any rate, the science games didn’t draw much of an audience. Hardly anyone knew enough to follow them. And mathematicians—they were dressed in black robes and held slates and chalk—were ignored, even if they were gold medalists. The social sciences drew the crowds, probably because anyone could, in a way, feel he was participating in them. But we writers didn’t do so badly. No one read what we wrote, but a lot of people enjoyed our public displays. At least one writer was sure to crack up before the Games were over, and occasionally there was a suicide.

We marched around, the flame was lit, and I smiled at Jules. At least we were contenders. No one could take that away.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 20»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 20» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 20» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.