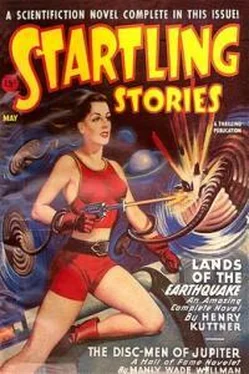

Генри Каттнер - Lands of the Earthquake

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Генри Каттнер - Lands of the Earthquake» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2017, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lands of the Earthquake

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2017

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lands of the Earthquake: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lands of the Earthquake»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lands of the Earthquake — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lands of the Earthquake», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Guillaume had told Boyce the word that would let him in.

“Say you come to worship Nain ,” he said. “You need only that one name— Nain . Many of the pilgrims do not know the tongue the City speaks, so you will not need to know it. You can make yourself understood. The people of the streets speak a patois of which our own French tongue has become a part in the long time we have lived in Kerak.”

He hesitated, a look of bewilderment overspreading the exhaustion of his face, but he did not think that idea through. It was as well.

Kerak and the City must have lain anchored together on the drifting lands for a long time indeed, if the old French had incorporated itself into the street patois.

“You must ask the way to Nain’s temple,” Guillaume went on. “One will meet you there when you have done as I told you. After that—” He shrugged. “ Dieu lo vult. ”

A gateway in the wall loomed up at Boyce’s right. It was closed. Upon the panels a painted face with staring yellow eyes regarded the fog. Boyce went on by, trying to shake off the illusion that the eyes rolled to watch him pass.

The next gate was open, but the insignia painted on the back–flung leaves was a standing dragon, and something about the scaled picture reminded him forcibly of that monstrous thing which had cast aside the garment of Hugh de Mandois’ body in the hall at Kerak. He wondered what he might find if he went in at this gateway—wondered if it was here that Hugh had entered—and passed quickly by.

The third gate was closed. A ring of blue lights glimmered on its panels. Boyce stood before it in the rolling fog, drew a deep breath.

This was the gate. Under this arch he must enter the enchanted City and find the answer to the questions which had driven him so long and so far.

He slipped his hand into his belt and touched the one thing he had brought with him from the outer world—that small, cold crystal which had cast its web of light upon a wall and opened a window for his entrance. It lay there against his side, hard, cold with a faint chill that struck through his clothing. It was his only link with her —nameless and faceless—and the lost year he had sought so long.

Perhaps he might find his answer soon.

He lifted his hand and knocked faintly upon the gate. There was a long silence. Then with a sighing of hinges the blue–lit door swung open.

Music drifted through it, and someone’s light laughter from far away.

Boyce squared his shoulders and stepped forward.

He entered the City of Sorcerers.

Chapter VIII

The Called Bluff

“Kerak’s quarrel,” Guillaume had said, “is with the Sorcerer King and the men about him. The common folk of the city know little about us and care less. You can go safely among them—or as safely as anyone may go who enters for a pilgrimage. That is not very safe, du Boyce. Go carefully.”

The man who looked out of the opened gate bore out Guillaume’s warning. He was a swarthy, small man with shifty eyes and a bandage around his head. He gave Boyce a look of indifferent dislike and said something in a tone of bored inquiry.

Boyce said, “ Nain .”

The gatekeeper nodded and stood back. Boyce bent his head under the low archway and stepped into the street within.

It was a narrow street, walled by high, narrow houses. Colored lanterns hung here and there from upper windows, and the pavement was wet with fog, reflecting the lamplight. A curious city, Boyce thought, in which it must seem always just dusk, with the first lamps lighted in the streets.

This was a street of music and merrymaking, to judge by the sounds that came from the windows he passed. Most of them were set with tiny diamond–shaped panes that distorted the scenes within, but he caught glimpses of confused colors and shifting bodies and heard laughter and the smell of wine drifted from every open door. There was strange, wild music that sent its rhythm echoing involuntarily through his mind.

The people on the street were a mixed lot. Tall, fair men in striped robes that billowed around their long strides—short men, red–skinned, in turbans and tight–fitting coats—women with perfectly transparent veils across their faces, who smiled indiscriminately upon every passerby—women the color of polished ebony, who wore broadswords and swaggered as they walked in their scarlet tunics down the middle of the street.

Boyce, tall and fair–haired, in his blue cloak and scarlet–crossed tunic, had no reason to feel conspicuous in that crowd. No doubt there were symbols upon the garments of many others with meanings as esoteric as those on his, drawn, perhaps, from the worlds as unknown here as Earth.

He passed a little man in grey rags, who carried a striped paper lantern over his shoulder on a long stick, and touched the man’s arm, saying, “ Nain? ”

The man smiled at him and nodded up the street, indicating a turn at the next corner. Boyce thanked him in English, grinned to himself to hear how fantastic the familiar tongue sounded in this dim, wet street, and went on.

Twice more he asked his way, once of a grim–faced woman wearing a horned helmet and a green velvet robe that swept the ground, once of a man in armor whose plates glinted like mirrors in the light of the colored lanterns. On the third try, he found the temple he sought.

It was a big stone building, lightless, without windows, standing in the center of a square. The streets parted around it, flowing noisily with colorful crowds, but the temple of Nain maintained its austere silence even in the midst of that rioting crowd.

Boyce climbed the grey stone steps and paused under the archway at their top to look down a long room that twinkled around its walls with row upon mounting row of colored globes, thousands upon thousands of them, each burning in its paper lantern upon shelves that lined the walls. There were others here, a throng as motley as the street crowds, strolling and whispering through the big empty room. If there were ceremonies in honor of Nain , evidently they had not yet begun.

Boyce went straight down the room toward a translucent wall at the far end. Guillaume had said there was a magical tree growing there. He found it was a tree of glass, espaliered flat against the crystal wall. Clusters of luminous, richly colored fruit dangled within the worshiper’s reach.

Calmly Boyce reached up and pulled a round blue fruit the size and shape of a pear. It vibrated in his hand for a moment, as alive and resilient as something of blown glass. Then there was a tiny exploding sound and the fruit vanished, leaving only a drop of blue moisture in his palm.

Someone touched his arm from behind. He whirled a little too quickly. It was a brown girl, barefooted, bare limbed, with gold bands on her wrists and ankles and a heavy gold collar locked around her throat.

She said, “Come,” in the old French, spoken with an accent that might be the City patois, and led him back down the room toward a side door. They came out upon another street, lined with great crouching stone beasts that shone with the moisture of the fog.

The beasts had lanterns around their necks and the crowd went by under their stone jowls in the swinging light of the lamps. The brown girl beckoned to Boyce and then hurried down the steps on soundless bare feet and plunged into the throng.

There was something wrong with this crowd. He was not sure just what, but he saw how the people kept glancing over their shoulders uneasily. Their noise was a little hysterical now. Sometimes they looked up, into the misty sky, and presently Boyce heard a thin, shrill keening overhead that was louder than the noise of the crowd, and grew louder still as he paused to listen.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lands of the Earthquake»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lands of the Earthquake» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lands of the Earthquake» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Генри Каттнер - Очи Тхара [The Eyes of Thar]](/books/28174/genri-kattner-ochi-thara-the-eyes-of-thar-thumb.webp)

![Генри Каттнер - Сын несущего расходы [= Сын волынщика; Один из несущих расходы]](/books/255796/genri-kattner-syn-nesuchego-rashody-syn-volynchik-thumb.webp)