The black man was looking at him.

Buckman walked toward the black man. The black man did not retreat; he stood where he was. Buckman reached him, held out his arms and seized the black man, enfolded him in them, and hugged him. The black man grunted in surprise. And dismay. Neither man said anything. They stood for an instant and then Buckman let the black man go, turned, walked shakingly back to his quibble.

“Wait,” the black man said.

Buckman revolved to face him.

Hesitating, the black man stood shivering and then said, “Do you know how to get to Ventura? Up on air route thirty?” He waited. Buckman said nothing. “It’s fifty or so miles north of here,” the black man said. Still Buckman said nothing. “Do you have a map of this area?” the black man asked.

“No,” Buckman said. “I’m sorry.”

“I’ll ask the gas station,” the black man said, and smiled a little. Sheepishly. “It was—nice meeting you. What’s your name?” The black man waited a long moment. “Do you want to tell me?”

“I have no name,” Buckman said. “Not right now.” He could not really bear to think of it, at this time.

“Are you an official of some kind? Like a greeter? Or from the L.A. Chamber of Commerce? I’ve had dealings with them and they’re all right.”

“No,” Buckman said. “I’m an individual. Like you.”

“Well, I have a name,” the black man said. He deftly reached into his inner coat pocket, brought out a small stiff card, which he passed to Buckman. “Montgomery L. Hopkins is the handle. Look at the card. Isn’t that a good printing job? I like the letters raised like that. Fifty dollars a thousand it cost me; I got a special price because of an introductory offer not to be repeated.” The card had beautiful great embossed black letters on it. “I manufacture inexpensive biofeedback headphones of the analog type. They sell retail for under a hundred dollars.”

“Come and visit me,” Buckman said.

“Call me,” the black man said. Slowly and firmly, but also a little loudly, he said. “These places, these coin-operated robot gas stations, are downers late at night. Sometime later on we can talk more. Where it’s friendly. I can sympathize and understand how you’re feeling, when it happens that places like this get you on a bummer. A lot of times I get gas on my way home from the factory so I won’t have to stop late. I go out on a lot of night calls for several reasons. Yes, I can tell you’re feeling down at the mouth—you know, depressed. That’s why you handed me that note which I’m afraid I didn’t flash on at the time but do now, and then you wanted to put your arms around me, you know, like you did, like a child would, for a second. I’ve had that sort of inspiration, or rather call it impulse, from time to time during my life. I’m forty-seven now. I understand. You want to not be by yourself late at night, especially when it’s unseasonably chilly like it is right now. Yes, I agree completely, and now you don’t exactly know what to say because you did something suddenly out of irrational impulse without thinking through to the final consequences. But it’s okay; I can dig it. Don’t worry about it one damn bit. You must drop over. You’ll like my house. It’s very mellow. You can meet my wife and our kids. Three in all.”

“I will,” Buckman said. “I’ll keep your card.” He got out his wallet, pushed the card into it. “Thank you.”

“I see that my quibble’s ready,” the black man said. “I was low on oil, too.” He hesitated, started to move away, then returned and held out his hand. Buckman shook it briefly. “Goodbye,” the black man said.

Buckman watched him go; the black man paid the gas station, got into his slightly battered quibble, started it up, and lifted off into the darkness. As he passed above Buckman the black man raised his right hand from the steering wheel and waved in salutation.

Good night, Buckman thought as he silently waved back with cold-bitten fingers. Then he reentered his own quibble, hesitated, feeling numb, waited, then, seeing nothing, slammed his door abruptly and started up his engine. A moment later he had reached the sky.

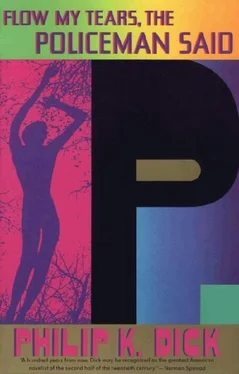

Flow, my tears, he thought. The first piece of abstract music ever written. John Dowland in his Second Lute Book in 1600. I’ll play it on that big new quad phonograph of mine when I get home. Where it can remind me of Alys and all the rest of them. Where there will be a symphony and a fire and it will all be warm.

I will go get my little boy. Early tomorrow I’ll fly down to Florida and pick up Barney. Have him with me from now on. The two of us together. No matter what the consequences. But now there won’t be any consequences; it’s all over. It’s safe. Forever.

His quibble crept across the night sky. Like some wounded, half-dissolved insect. Carrying him home.

Hark! you shadows that in darkness dwell,

Learn to condemn light.

Happy, happy they that in hell

Feel not the world’s despite.

The trial of Jason Taverner for the first-degree murder of Alys Buckman mysteriously backfired, ending with a verdict of not guilty, due in part to the excellent legal help NBC and Bill Wolfer provided, but due also to the fact that Taverner had committed no crime. There had in fact been no crime, and the original coroner’s finding was reversed—accompanied by the retirement of the coroner and his replacement by a younger man. Jason Taverner’s TV ratings, which had dropped to a low point during the trial, rose with the verdict, and Taverner found himself with an audience of thirty-five million, rather than thirty.

The house which Felix Buckman and his sister Alys had owned and occupied drifted along in a nebulous legal status for several years; Alys had willed her part of the equity to a lesbian organization called the Sons of Caribron with headquarters in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, and the society wished to make the house into a retreat for their several saints. In March of 2003 Buckman sold his share of the equity to the Sons of Caribron, and, with the money derived, moved himself and all the items of his many collections to Borneo, where living was cheap and the police amiable.

Experiments with the multiple-space-inclusion drug KR-3 were abandoned late in 1992, due to its toxic qualities. However, for several years the police covertly experimented with it on inmates in forced-labor camps. But ultimately, due to the general widespread hazards involved, the Director ordered the project abandoned.

Kathy Nelson learned—and accepted—a year later that her husband Jack had been long dead, as McNulty had told her. The recognition of this precipitated a blatant psychotic break in her, and she again was hospitalized, this time for good at a far less stylish psychiatric hospital than Morningside.

For the fifty-first and final time in her life Ruth Rae married, in this terminal instance, to an elderly, wealthy, potbellied importer of firearms located in lower New Jersey, barely operating within the limit of the law. In the spring of 1994 she died of an overdose of alcohol taken with a new tranquilizer, Phrenozine, which acts as a central nervous system depressant, as well as suppressing the vagus nerve. At the time of her death she weighed ninety-two pounds, the result of difficult—and chronic—psychological problems. It never became possible to certify with any clarity the death as either an accident or a deliberate suicide; after all, the medication was relatively new. Her husband, Jake Mongo, at the time of her death had become heavily in debt and outlasted her barely a year. Jason Taverner attended her funeral and, at the later graveside ceremony, met a girl friend of Ruth’s named Fay Krankheit, with whom he presently formed a working relationship that lasted two years. From her Jason learned that Ruth Rae had periodically attached herself to the phone-grid sex network; learning this, he understood better why she had become as she had when he met her in Vegas.

Читать дальше