Lisa’s family owned their own land and measured everything by soil and water and sweat; not stopping and whining if the tractor broke or the mule died. They themselves were raised by a generation of men that went to war, leaving their legacy to a generation of strong women who would tend to it until their return. To their children, they passed on something you could hold in your hand, not press into an ATM machine.

As a young girl, she loved the old John Wayne movies her parents had recorded. She could never forget the climactic moment in one film where the grizzled old marshal confronts the four villains and calls out: “I mean to kill you or see you hanged at Judge Parker’s convenience. Which will it be?”

“Bold talk for a one-eyed fat man,” their leader sneers.

Then Duke cries, “Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!” and, reins in his courage, rushing at them while firing both guns. Those four outlaws did not provide a threat at the next sunset.

When did her homeland change so? The west Lisa grew up in is now more socialized and urban, more of the citizens pining for things they cannot afford while looking to others to fix their problems. Where she grew up, gardens were tended and food canned, and when threatened by others the wagons were circled and folks cared for themselves, providing for their own, from the land and their hard work.

Her Dad was a third-generation farmer, her mom coming to the San Joaquin Valley as a young bride, and she often told her daughter that she learned fast. There were stories of spring snowstorms thawing into mucky puddles from which a season of new life came. There would be drought and there would be searing heat. Sometimes the crops were abundant, other times not so much. There were a few years that in addition to tending to the almond trees and other growing things, Dad worked as a telephone lineman, just to keep a roof over their heads.

It was not an easy life, especially when sometimes Mom and she were left during the day to do everything themselves. To do otherwise would have left the place in ashes, abandoned, another failed dream. Duty and honor weren’t archaic promises; they were words she was raised to live on, no matter how bad things got. Being so small, the idea of ‘too big to fail’ never made sense.

You saw it there in those last days of California as part of the nation, in the eyes at the feed store, you see it in the determined step of those buying supplies and learning the use them. You saw it in the questions of the many that may have been in the minority with this whole secession idea but were not willing to leave the land where they had lived their entire life. People that are beginning to understand that we have a right to be heard, not silenced because the majority disagreed with us.

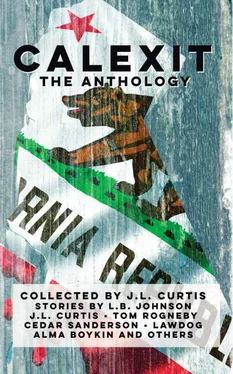

Because we’re NOT too big to fail and this Calexit thing has a big fail written all over it. She thinks of the movie War of the World’s wherein the monolithic war machines of Mars were felled by something as simple as a sneeze.

She is intensely proud of being an American. She refused to say was proud of being an American, the being and cadence of a life of freedom, to work, to arm oneself, to defend and expand that which you personally worked for. Influenced by a bygone era of good guys and bad guys, it is part of who she was, defining both fury and faith.

Because in coming days she is afraid she will find what she is made of.

She’s been out here on her own for two months now. There is still electricity and she hopes it continues through the looming winter. From the distance, she has heard at least one car, but no one has attempted her rough dirt track up the hillside into the forest; it is almost impossible to see from the road now. Even when she first moved here, with empty cabins near that might invite a break-in; she laid out tree limbs and such to partially block the narrow path that behind the trees widened to the long dirt road to her home. It was easy enough to clear out when she had a dog grooming client expected but reduced the chances of a home break in. Now she has no clients and she has let the undergrowth take over, but she still had room to get out in an emergency.

She was afraid to take her truck onto the main road into town, which was miles away, after one late night telephone conversation with her neighbor John who lived about a mile down the mountain from her. He was in his sixties, divorced, his grown kids living near Sacramento.

He had told her, “Lisa — don’t take your truck out on the road. My kids told me they are taking vehicles from the middle and upper classes, and giving them to the poor, redistributing them for those that are joining the militia.”

“Militia?” was all she could stammer.

“The Militia is preventing people from leaving except with what they can carry and they have to walk out. It’s been reported that some people were shot when they tried to drive over the border.”

She was stunned, not believing such things were happening. She’d heard gunshots from a great distance, but she convinced herself that was a neighbor who had hunkered down out hunting for food.

Today she’s going to take her horse, Taxi, out east of her property. She lives high up on a ridge, where there are just two other homes, both long empty and for sale, as people abandoned the state. She is on the east side and if she keeps to the trails east of her home, it will take her in deep forest that eventually leads to an unnamed valley that goes down to the Nevada State line, a couple dozen miles away. It was rough, rugged country, but she was familiar with many of the trails, regularly taking the horse out on the trail rides they both love.

In keeping with what her distant neighbor told her, she didn’t take the horse along the trail that paralleled the road into town, and then up to the lake, she stayed back a few yards into the tree line. Needing a short break and a drink she tethered Taxi to a tree and got down to clear a limb that they had maneuvered around last time, but needed to be cleared from the trail. She thought for a moment she heard a car door but figured it was her imagination as she had not seen anyone on this road in weeks.

As she bent down to pick up the limb, a bullet whizzed over her head.

“He’s back there!” is all she heard as she took off running. She tripped, falling and breaking open the skin on the palm of her hand on a sharp rock. It wasn’t terribly deep but it is painful, and she bites her tongue to keep from crying out as she stumbles the last few feet to her horse.

Lisa wasn’t sure what “he” they were referring to, but with her long red hair under a baseball cap and clothing that would never land her on the cover of Cosmo Magazine on her tall frame, she figured the bullet was addressed to her.

She has two advantages — back in the trees, the sun’s rays are disoriented and dim. Although it pours down a leaden heat on the landscape, the light wavers and it will take whoever had fired the shot a minute or two to adjust to it. That should give her about one hundred yards. If they have a four-wheeler, she is toast, but they are likely were on foot, with the trail not being suited for a vehicle.

Other shots fly behind her, not as close now, as she deliberately heads away from her home. She hears another car door slam from the road and some shouting as she headed high up the next ridgeline.

She was far enough away from her home when that first shot rang out that it was unlikely they would find it on a search for her, but she needs to find her way back miles further away from the road. There are creeks with water for Taxi, and she has some protein bars, some tarp and rope, and a knife in her backpack should she need to spend the night outdoors before making her way home. Once she could no longer hear anyone else, she removed her bra and wound it around her bloody palm to help staunch the blood flow after washing it out with a bit of her bottled water and some iodine she keeps in her pack.

Читать дальше