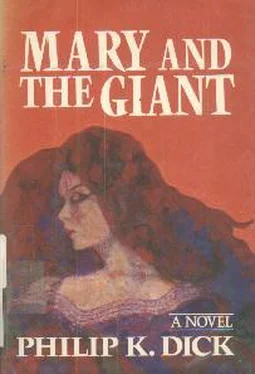

Philip Dick - Mary And The Giant

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Dick - Mary And The Giant» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mary And The Giant

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mary And The Giant: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mary And The Giant»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mary And The Giant — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mary And The Giant», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I've never heard him. We're still waiting."

"I'm not talking about Tweany," Nitz said, evidently aware of his moral lapse. "Not particularly, I mean. I'm talking about folk music in general."

"But this Tweany is a folksinger," the blonde said. "So where does he stand?"

Nitz uneasily sipped his drink. "It's hard to say. I'm just the intermission pianist ... a mortal."

"You don't like his stuff," the blonde's companion said with a knowing wink.

"I'm a bop player." Nitz reddened and avoided the girl's accusing glare. "To me, folk music is like Dixie: a dead horse. It stopped growing back in the days of James Merritt Ives. Show me a folk song that's come down since then."

She was quite angry now; the need to defend Tweany, to keep the greatness of him intact, made her bristle and say: "What about 'Ol' Man River'?" Tweany sang "O1' Man River" at least once a night, and it was one of her favorites.

At that, Nitz grinned. "See what I mean? 'Ol' Man River' was written by Jerome Kern."

He broke off, because at that moment there was applause, and Carleton Tweany appeared on the raised platform. Instantly, the girl forgot Nitz, forgot the blonde and everything else. The conversation fell into a vacuum.

"Excuse me," Nitz murmured. He crawled back to his piano, dwarfed, she observed, by the huge figure of Tweany.

"For my first number," Tweany rumbled in his furry singsong, "I will sing a work that expresses the bitter terror of the Negro people in their ages of bondage. You may have heard it before." He paused. " 'Strange Fruit.' "

A flutter of excitement stirred the room as Nitz picked out a few opening chords. And then, his arms folded, his head down, forehead wrinkled in contemplation, Tweany began. He did not raise his voice or shout; he did not bellow or snarl or shake his fist. Thoughtful, deeply moved, he spoke directly to the people around him; it was a highly personal communication and not a concert rendition.

When he had finished telling them the story of life in the South, there was silence. Nobody clapped; the people clustered around waited with fearful expectancy, as Tweany considered his next communication.

"My people," he murmured, "have suffered greatly in their chains and tribulations. Their lot has not been a happy one. But the Negro can sing about his privations. This is a song from the heart of the Negro people. In it he expresses his deeply felt sufferings, but, at the same time, his genuine humor. He is, innately, a happy person. What he wants is the simple things of life. Enough to eat, a place to sleep, and most important, a woman."

Carleton Tweany thereupon sang "Got Grasshoppers in My Pillow, Baby, Got Crickets All in My Meal."

Mary Anne listened tensely, following every word, her eyes on the man a few feet from her. In the last months she had not been close to Tweany; except for these public moments, she had seen little of him She wondered if he was singing to her; she tried to find in his words some special reference to herself and things they had done together. Bland and withdrawn, Tweany continued to sing, not noticing her, apparently unaware of her.

Beside her the blonde listened, too. Her companion was uninterested; sunk down in a brooding heap, he squeezed and pressed a piece of wax that had dripped from the candle.

"For my last number," Tweany declared when he had finished, "I shall sing a composition that has found special favor in the hearts of Americans, both Caucasian and Negro. It is a song that unites all of us in memories as we near the moment in which we celebrate the birth of One Who died to redeem us all, whatever our race, whatever our color."

Half-closing his eyes, Tweany sang "White Christmas."

At the piano, Paul Nitz plunked chords dutifully. Mary Anne, as she listened to the tune grind along, wished she could tell what was in the minds of the two men. Nitz, hunched over at the keys, seemed merely bored-as if he were pushing a broom, she reflected. She felt indignation at Nitz's betrayal of artistry. Was that all it meant to him? As if he were on an assembly line ... she hated him for betraying Tweany. It was an insult to Tweany; he could show some feeling. And Tweany-what, if anything, was he thinking?

It seemed, almost, as if there was a cynical smile on Tweany's face, an emptiness that could have been the most muted kind of contempt. But contempt for whom? For the song? But he had picked it. For the people listening? As he sang-or rather muttered out the lyrics-Tweany's expression began to undergo a metamorphosis. The detachment began to fade; in its place appeared a fervor. His voice took on a throbbing sublimity, a grandeur that grew until he appeared to be vibrating with pain. There was no doubting his emotions: Tweany loved the song. He was terribly moved. And he was communicating that to the audience.

When he had finished there was once more the interval of silence, and then the applause exploded wildly. Tweany stood, shaken, his face impassioned. Then, gradually, grief sank and the half-cynical listlessness returned. Tweany shrugged, straightened his expensive hand-painted necktie, and stepped to the floor.

"Tweany!" Mary Anne called shrilly, jumping to her feet. "Where were you last night? I came over and you weren't home."

With a faint twitch of his eyebrows-two lines of expressive, cultivated black-Tweany acknowledged her existence. He stepped over to the table and stood for a moment with his hand on the chair Nitz had vacated.

The blonde said: "Why don't you join us?"

"Thank you," Tweany replied. He rotated the chair and seated himself. "I'm tired."

"Don't you feel good?" Mary Anne asked, concerned; he did look wilted.

"Not so good."

Nitz dropped down beside him and said: "I hate that goddamn 'White Christmas' worse than any other tune in the business. The joker that wrote that should be shot."

Sadness overcame Tweany. "Oh?" he murmured. "Do you feel that?"

Sipping his drink, Nitz said: "What do you know about the sufferings of the Negro people? You were born in Oakland, California."

The blonde, to Mary Anne's annoyance, leaned forward and addressed Tweany. "That song about grasshoppers ... that's an old Leadbelly tune, isn't it?"

Tweany nodded. "Yes, Leadbelly used to sing that, before he passed away.

"Did he record it?"

"He did," Tweany said absently. "But it's not available now.

It's more or less a collector's item."

"Maybe Joe has it," the blonde said to her companion.

"Ask him," her companion said, without enthusiasm. "You're in there enough."

The discussion of folk music resumed, and Mary Anne managed to catch Tweany's attention.

"You didn't say where you were last night," she said accusingly.

A cunning smile settled over Tweany's face; the usual film glazed his eyes until they were a dulled, dispassionate gray. "I was busy. I've been rather occupied, the last few weeks."

"Months, you mean."

Half-listening to Nitz and the blonde rambling on about

Blind Lemon Jefferson, Tweany asked: "How's the Pacific Tel and Tel?"

"Lousy."

"I'm sorry to hear that."

In a clear voice Mary Anne informed him, "I'm going to quit."

"Already?"

"No. Not until I have something else. I've learned my lesson."

"You wish you were back at the furniture place? Ask them they'll take you back."

"Don't kid me. I wouldn't go back there on a bet."

"Suit yourself." Tweany shrugged. "It's your life."

"Why did you throw me out when I came to you that day?"

"I didn't throw you out. I don't recall doing that."

"You wouldn't let me move my things over. You made me keep a separate address, and after a week you wouldn't let me stay all night. I had to get up and leave-that's what I call being thrown out."

He regarded her with wonder. "Are you out of your mind? You know the situation. You're under age. It's a felony."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mary And The Giant»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mary And The Giant» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mary And The Giant» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.