'We had to stretch it,' said Shankar, 'to be able to identify the individual components. So we slowed it right down until the scratching noise became a sequence of individual pulses varying in length and intensity.'

'Sounds like Morse code,' said Weaver.

'It seems to work like it too.'

'How are you transcribing it?' asked Li. 'With spectrograms?'

'Yes, but they aren't enough. When it's a question of listening to something, it's always better to hear it. So we used an acoustic trick. It's a bit like false colour being added to radar images to show up the detail. In this instance we took each individual sound and replaced it with a frequency that we can hear, while keeping its original length and intensity. Whenever the original signal switched frequencies, we modified ours. That's how we handled Scratch.'

Crowe punched something into the keyboard. 'The sound we detected is like this.'

There was a rumble, like an underwater drum. The beats followed in quick succession, almost too fast to tell apart, but there could be no doubt that they were listening to a sequence of noises that varied in volume and duration.

'Well, it sounds like code,' said Anawak, 'but what does it mean?'

'We don't know.'

'You don't know?' echoed Vanderbilt. 'But I thought you'd cracked it.'

'What we don't know,' Crowe explained patiently, 'is how their language might work when they're using it normally. We can't make head or tail of the previous Scratch signals. But that's beside the point.' Smoke curled from her nostrils. 'We've got something better. We've got contact. Murray, show them the first part.'

Shankar clicked on an icon. The screen was lined with rows of numbers. Some columns seemed identical.

'We sent them some homework, as you know,' said Shankar. 'Math questions. Like an IQ test. We asked them to continue decimal sequences, work out some logarithms, fill in the missing numbers, that kind of thing. If it worked, we were hoping they'd find it kind of fun and send us a reply. It would be their way of telling us that they'd heard us, that they really exist, that they know about math and can manipulate numbers.' He pointed to the rows of figures on the screen. 'This is their answer. Grade A. They got everything right.'

'Christ,' whispered Weaver.

'That tells us two things,' said Crowe. 'First, Scratch is indeed a kind of language. In all probability, each of the Scratch signals contains complex information. Second, and this is the decisive point, it proves that they're capable of adapting Scratch so that we can understand it. That's an achievement of the highest order. It tells us that they're every bit as smart as we are. They're capable of decoding our messages; but they can also code their own.'

For a while they just stared at the columns of figures, admiration mixed with fear.

'But what does it prove?' asked Johanson, breaking the silence.

'I should have thought that was obvious,' retorted Delaware. 'It proves something's down there. Something that can think.'

'OK, but couldn't a computer generate the same results?'

'You don't think we're talking to a computer, do you?'

'He's got a point, you know,' said Anawak. 'All it proves is that our math questions have been answered. That's impressive, but it's not evidence of conscious intelligence.'

'But what else could be sending us messages?' asked Greywolf, disbelievingly. 'Mackerel?'

'Nonsense. Think about it. What we're seeing here is the work of a creature that can manipulate symbols. That's not proof of higher intelligence per se . Take chameleons, for instance. They solve a highly complex processing problem every time they change colour, but they've got no idea they're doing it. If you weren't acquainted with the IQ of chameleons, you might suppose they're very clever – after all, they can use a program that allows them to resemble foliage one day and a rock face the next. You'd probably credit them with enormous insight because they're reading the code of their surroundings. And you'd assume they were creative because they change their code to match.'

'So what are we looking at?' asked Delaware, helplessly.

Crowe smiled. 'Leon's right,' she said. 'Just because someone can manipulate symbols doesn't mean they understand them. The real proof of intelligence and creativity resides in a creature's ability to understand and conceptualise conditions in the real world. That requires a deeper understanding. Even the most highly powered computer doesn't deal in rules of thumb or counter-intuitive decisions. It can't engage with its environment or experience the world. I imagine the yrr had the same considerations in mind when they formulated their reply. They tried to find something that would signal to us they're capable of real understanding.' Crowe pointed to the screen. 'These are the results of the two math problems. If you look closely, you'll see that the first answer appears eleven times in a row, then you get three repetitions of answer number two, a single occurrence of answer number one, then nine times number two and so on. At one point the second answer appears nearly thirty thousand times. But why? It makes sense to send us the results more than once, of course, even if only to make sure that the message is long enough to be detected. But why would they mix them all together?'

'This is where Ms. Alien comes in,' said Shankar, with an enigmatic smile.

Jodie Foster, my alter ego ! Crowe nodded. 'I have to admit that if it hadn't been for the movie, I would never have got there so quickly. You see, the sequence of answers is a code in itself. If you know how to read it, you get an image of black and white pixels – just like the messages we work on at SETI'

'I hope it's not a picture of Hitler,' said Rubin. This time he was rewarded with a laugh. By now everyone on board had seen Contact . It was about extra-terrestrials transmitting an image to Earth. The pixels of the image contained the manual for a spaceship. Humanity had been beaming pictures into space throughout its high-tech evolution, and the aliens had picked one at random as the basis for their message. Of all the available images, they'd chosen one of Hitler.

'No,' said Crowe. 'It's not Hitler.'

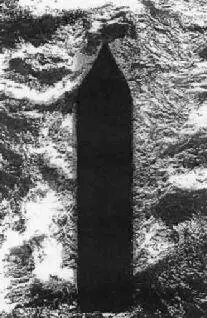

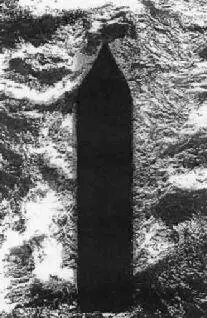

Shankar hit a few keys. The columns of figures disappeared and made way for an image.

'What is it?' Vanderbilt leaned forward to get a better look.

'Don't you recognise it?' asked Crowe. 'Any suggestions?'

'Looks like a skyscraper,' said Anawak.

'The Empire State Building?' suggested Rubin.

'Yeah right,' said Greywolf. 'How are they supposed to know what the Empire State Building looks like? I'd say it's a missile.'

'And how would they know what a missile looks like?' asked Delaware.

'They're lying all over the seabed! Nuclear missiles, chemical missiles…'

'What's all this stuff in the background?' asked Oliviera. 'Clouds?'

'It could be water,' said Weaver. 'Maybe it's a picture of the depths. Some kind of rock formation.'

'You're on the right track with water,' said Crowe.

Johanson scratched his beard. 'It looks more like a monument. Maybe it's a symbol. Something… religious.'

'That's a human idea if ever I heard one.' Crowe seemed to be enjoying herself enormously. 'Hasn't it occurred to you that there might be another way of looking at the picture?'

They stared at it again. Li gave a start. 'Can you rotate it by ninety degrees?'

Shankar's fingers danced over the keyboard and the picture shifted to the horizontal.

'I still don't get what it is,' said Vanderbilt. 'A fish? A huge animal?'

Li chuckled to herself 'No, Jack. Those are waves in the background. It's a snapshot taken from below. We're looking at the surface – from the perspective of the depths.'

Читать дальше