“But you took it away again,” I said gently.

Her hand groped across the table. I took it in mine, and held it for a while.

“Were you planning to do the same to us?” I asked, when she seemed to have calmed. She tried to withdraw her hand, but I held onto it.

“It doesn’t matter now,” I said urgently. “These things are done, all you have to do now is live with them. That’s how you do it, Tanya. Just admit it if it’s true. To yourself, if not to me.”

A tear leaked out of the corner of one eye in the rigid face opposite me.

“I don’t know,” she whispered. “I was just surviving.”

“Good enough,” I told her.

We sat and held hands in silence until the waiter, on some aberrational whim, came to see if we wanted anything else.

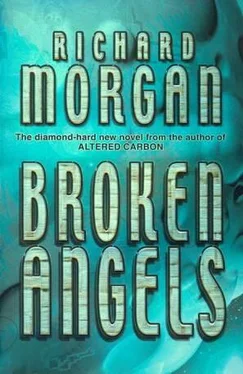

Later, on our way back down through the streets of Dig 27, we passed the same junk salvage yard, and the same Martian artefact trapped in cement in the wall. An image erupted in my mind, the frozen agony of the Martians, sunk and sealed in the bubblestuff of their ship’s hull. Thousands of them, extending to the dark horizon of the vessel’s asteroidal bulk, a drowned nation of angels, beating their wings in a last insane attempt to escape whatever catastrophe had overwhelmed the ship in the throes of the engagement.

I looked sideways at Tanya Wardani, and knew with a flash like an empathin rush that she was tuned in to the same image.

“I hope he doesn’t come here,” she muttered.

“Sorry?”

“Wycinski. When the news breaks, he’ll. He’ll want to be here to see what we’ve found. I think it might destroy him.”

“Will they let him come?”

She shrugged. “Hard to really keep him out if he wants it badly enough. He’s been pensioned off into sinecure research at Bradbury for the last century, but he still has a few silent friends in the Guild. There’s enough residual awe for that. Enough guilt as well, the way he was treated. Someone’ll turn the favour for him, blag him a hypercast at least as far as Latimer. After that, well he’s still independently wealthy enough to make the rest of the running himself.” She shook her head. “But it’ll kill him. His precious Martians, fighting and dying in cohorts just like humans. Mass graves and planetary wealth condensed into war machines. It tears down everything he wanted to believe about them.”

“Well, predator stock…”

“I know . Predators have to be smarter, predators come to dominate, predators evolve civilisation and move out into the stars. That same old fucking song.”

“Same old fucking universe,” I pointed out gently.

“It’s just…”

“At least they weren’t fighting amongst themselves any more. You said yourself, the other ship wasn’t Martian.”

“Yeah, I don’t know. It certainly didn’t look it. But is that any better? Unify your race so you can go beat the shit out of someone else’s. Couldn’t they get past that?”

“Doesn’t look like it.”

She wasn’t listening. She stared blindly away at the cemented artefact. “They must have known they were going to die. It would have been instinctive, trying to fly away. Like running from a bomb blast. Like putting your hands out to stop a bullet.”

“And then the hull what, melted?”

She shook her head again, slowly. “I don’t know, I don’t think so. I’ve been thinking about this. The weapons we saw, they seemed to be doing something more basic than that. Changing the,” she gestured, “I don’t know, the wavelength of matter? Something hyperdimensional? Something outside 3-D space. That’s what it felt like. I think the hull disappeared, I think they were standing in space, still alive because the ship was still there in some sense, but knowing it was about to flip out of existence. I think that’s when they tried to fly.”

I shivered a little, remembering.

“It must have been a heavier attack than the one we saw,” she went on. “What we saw didn’t come close.”

I grunted. “Yeah, well, the automated systems have had a hundred thousand years to work on it. Stands to reason they’d have it down to a fine art by now. Did you hear what Hand said, just before it got bad?”

“No.”

“He said this is what killed the others . The one we found in the corridors, but he meant the others too. Weng, Aribowo, the rest of the team. That’s why they stayed out there until their air burned out. It happened to them too, didn’t it.”

She stopped in the street to look at me.

“Look, if it did…”

I nodded. “Yeah. That’s what I thought.”

“We calculated that cometary. The glyph counters and our own instruments, just to be sure. Every twelve hundred standard years, give or take. If this happened to Aribowo’s crew as well, it means.”

“It means another near-miss intersection, with another warship. A year to eighteen months back, and who knows what kind of orbit that might be locked into.”

“Statistically,” she breathed.

“Yeah. You thought of that too. Because statistically, the chances of two expeditions, eighteen months apart both having the bad luck to stumble on deep-space cometary intersections like that?”

“Astronomical.”

“And that’s being conservative. It’s the next best thing to impossible.”

“Unless.”

I nodded again, and smiled because I could see the strength pouring back into her like current as she thought it through.

“That’s right. Unless there’s so much junk flying around out there that this is a very common occurrence. Unless, in other words, you’re looking at the locked-in remains of an entire naval engagement on a system-wide scale.”

“We would have seen it,” she said uncertainly. “By now, we would have spotted some of them.”

“Doubtful. There’s a lot of space out there, and even a fifty-klick hulk is pretty small by asteroidal standards. And anyway, we haven’t been looking. Ever since we got here, we’ve had our noses buried in the dirt, grubbing up quick dig/quick sale archaeological trash. Return on investment. That’s the name of the game in Landfall. We’ve forgotten how to look any other way.”

She laughed, or something very like it.

“ You’re not Wycinski, are you, Kovacs? Because you talk just like him sometimes.”

I built another smile. “No. I’m not Wycinski, either.”

The phone Roespinoedji had lent me thrummed in my pocket. I dug it out, wincing at the way my elbow joint grated on itself.

“Yeah?”

“Vongsavath. These guys are all done. We can be out of here by tonight, you want it that way.”

I looked at Wardani and sighed. “Yeah. I want it that way. Be down there with you in a couple of minutes.”

I pocketed the phone and started down the street again. Wardani followed.

“Hey,” she said.

“Yeah?”

“That stuff about looking out? Not grubbing in the dirt? Where did that come from all of a sudden, Mr. I’m-Not-Wycinski?”

“I don’t know.” I shrugged. “Maybe it’s the Harlan’s World thing. It’s the one place in the Protectorate where you tend to look outward when you think about the Martians. Oh, we’ve got our own dig sites and remains. But the one thing about the Martians you don’t forget is the orbitals. They’re up there every day of your life, round and round, like angels with swords and twitchy fingers. Part of the night sky. This stuff, everything we’ve found here, it doesn’t really surprise me. It’s about time.”

“Yes.”

The energy I’d seen coming back to her was there in her tone, and I knew then that she’d be alright. There’d been a point when I thought that she wasn’t staying for this, that anchoring herself here and waiting out the war was some obscure form of ongoing punishment she was visiting upon herself. But the bright edge of enthusiasm in her voice was enough.

Читать дальше