A hundred times I reviewed my scrapes and escapes in this Secret House, whether as Thecla alone, or as Severian and Thecla united, or as the old Autarch. I could not find the moment — yet it existed; and I began, as I walked on, to search those veiled lives that lie behind the last, memories that I have scarcely mentioned in this narrative, that dim as they grow stranger and stretch backward, perhaps, to Ymar, and behind Ymar to the Age of Myth.

Yet overwhelming all these shadowy lives — and incomparably more vivid, as a mountain may be seen to the very expression in its eyes when the forest about its base has sunk into a green haze — hurtled the white star that was myself. I was there also; and I saw before me, seemingly still very distant (though I knew it was much nearer than it appeared) the crimson sun that was to be, after so many centuries, simultaneously my destruction and my apotheosis. To its left and right, brave Skuld and sullen Verthandi seemed inconsequential moons. The night-dark dot of Urth crept across its face, nearly lost among its mottlings; and in the dying moments of that night I wandered, bewildered and wondering, underground.

Chapter XLII — Ding, Dong, Ding!

WHEN I HAD entered the secret house, I had scarcely known where I was bound. Or rather, I had scarcely been conscious of it; unconsciously, I had been directing my steps toward the Hypogeum Amaranthine, as I at length realized. I intended to learn who it was who sat the Phoenix Throne, and to reclaim it if I could. When the New Sun arrived, our Commonwealth would require a ruler who understood what had taken place; so I thought.

A certain door of the Secret House opened behind the velvet arras that hung behind the throne. I had sealed it with my word in the initial year of my reign; and I had hung the narrow space between the arras and the wall with bells, so that no one could walk there without making some sound that would be overheard by the occupant of the throne.

Now the door opened smoothly and silently at my command. I stepped out and closed it after me. The little bells, suspended upon silk threads, tinkled softly; above them larger bells, from whose tongues the threads hung, whispered with brazen voices and let fall a shower of dust.

I stood motionless, listening. At last the bells ceased their jingling, though not before I had heard the laughter of the small Tzadkiel in it.

“What is that ringing?” It was an old woman who spoke, her tones thin and cracked.

Another spoke in a man’s deep voice. I could not make out his words.

“Bells!” the old woman exclaimed. “We heard bells. Are you grown so deaf, chiliarch, that you didn’t hear them too?”

Now I wished indeed for the batardeau, with which I might have slit the arras and so peered out; as the deep voice spoke again, it struck me that others who had stood where I stood must have had the same thought, and sharp knives to boot. I searched the arras with my fingertips.

“They rang, we tell you. Send someone to inquire.”

Perhaps there were many such rents, for I found one in a breath, made by some watcher only a trifle, below my own height. Applying my eye to it, I saw that I stood three strides to the right of the throne. Only the hand of the occupant was visible to me where it lay upon the arm, as thin as that of an anatomy, a hand webbed with blue veins and spangled with gems.

Before the throne, head bent, crouched a form so vast that for a moment I thought it was that Tzadkiel who had commanded the ship. Its disordered hair was caked with blood.

Behind it stood a cluster of shadowy guardsmen, and beside it a helmetless officer whose insignia and virtually invisible armor marked him as the chiliarch of the Praetorians, though he was not, of course, the chiliarch who had held the post during my reign, nor the one whom I had carried down from the upright timber in an epoch now unimaginably distant.

Before the throne and thus almost out of my field of view, a ragged woman leaned upon a carven staff. She spoke just as I realized that she was there, saying, “They ring to welcome the New Sun, Autarch. The whole of Urth prepares for his coming.”

“In our childhood,” the old woman on the throne muttered, “we had little to do but read history. Thus we know that there have been a thousand prophets such as you, my poor sister — no, say a hundred thousand. A hundred thousand crazed paupers who fancied themselves great rhetors and sought to make themselves great rulers as well.”

“Autarch,” answered the ragged woman, “won’t you hear me? You speak of thousands and hundreds of thousands. A thousand times at least I have heard objections such as you bring, but you have not yet heard what I will say.”

“Go on,” the woman on the throne told her. “You may speak as long as you amuse us.”

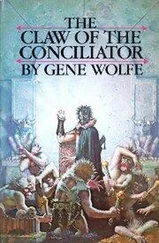

“I haven’t come to amuse you, but to tell you that the New Sun has come often before, seen perhaps by only a single person, or a few. You must recall the Claw of the Conciliator, for it vanished in our time.”

“It was stolen,” muttered the old woman who sat the throne. “We never saw it.”

“But I did,” the ragged woman with the staff said. “I saw it in the hands of an angel, when I was just a girl and very ill. Tonight as I was coming here I saw it again, in the sky. So did your soldiers, although they are afraid to tell you. So did this giant who has come as I have to warn you and has been savaged for it. So would you see it, Autarch, if you would quit this tomb.”

“There have been such portents before. They have portended nothing. It would take more than the sight of a bearded star to change our mind.”

I thought of stepping onto the stage then to end the play, if I could; and yet I remained where I was, wondering for whose entertainment such plays are staged. For it was a play, and in fact a play I had seen before, though never from the audience. It was Dr. Tabs’s play, with the old woman on the throne in a role the doctor had taken for himself, and the woman with the staff in one of the roles that had been mine.

I have just written that I chose not to step forth, and it is true. But in the very act of making my decision, I must have moved a trifle. The little bells laughed again, and the larger bell from whose tongue they depended struck once, though ever so softly.

“Bells!” the old woman exclaimed again. “You, sister, you witch or whatever you call yourself. Go out! There’s a guard at our door. Tell their lochage we wish to know why the bells ring.”

“I will not leave this place at your command,” the woman said. “I have answered your question already.”

The giant looked up at that, parting his lank hair with blood-smeared hands. “If bells ring, they’re ringing because a New Sun is coming,” he rumbled in a voice almost too deep to be understood. “I do not hear them, but I do not need to hear them.” Though I doubted my eyes, it was Baldanders himself.

“Are you saying we are mad?”

“My hearing is not acute. Once I studied sound, and the more one learns of that, the less one hears it. Then too, my tympanic membranes have grown too wide and thick. But I have heard the currents that scour the black trenches and the crash of the waves upon your shore.”

“Silence!” the old woman commanded.

“You can’t order the waves to be silent, madame,” Baldanders told her. “They are coming, and they are bitter with salt.”

One of the Praetorians struck the side of his head with the butt of his fusil; it was like the blow of a mallet.

Baldanders seemed unaffected. “The armies of Erebus follow the waves,” he said, “and all the defeats they suffered at your husband’s hands will be avenged.”

From those words I knew the identity of the Autarch, and the shock of seeing Baldanders once more was as nothing to that. I must have started, because the small bells rang loudly, and a larger one spoke twice.

Читать дальше