The Will of God cult believed the exact opposite. Doomsday had come at last, and no attempt should be made to avoid it. Indeed, it should be welcomed, since after Judgement those who were worthy of salvation would live in eternal bliss.

And so, from totally opposing premises, the Cauldwellites and the WOGs arrived at the same conclusion: The human race should not attempt to escape its destiny. All starships should be destroyed.

Perhaps it was fortunate that the two rival cults were so bitterly opposed that they could not cooperate even towards a goal that they both shared. In fact, after the death of President Windsor their hostility turned to internecine violence. The rumour was started — almost certainly by the World Security Bureau, though Bey’s colleagues had never admitted it to him — that the bomb had been planted by the WOGs and its timer sabotaged by the Cauldwellites. The exactly opposite version was also popular; one of them might even have been true.

All this was history, now known only to a handful of men besides himself and soon to be forgotten. Yet how strange that Magellan was once again threatened by sabotage.

Unlike the WOGs and the Cauldwellites, the Sabras were highly competent and not unhinged by fanaticism. They could therefore be a more serious problem, but Captain Bey believed he knew how to handle it.

“You’re a good man, Owen Fletcher,” he thought grimly. “But I’ve killed better ones in my time. And when there was no alternative, I’ve used torture.”

He was more than a little proud of the fact that he had never enjoyed it; and this time, there was a better way.

And now Magellan had a new crewmember, untimely awakened from his slumber and still adjusting to the realities of the situation — as Kaldor had done a year ago. Nothing but an emergency justified such action. But according to the computer records only Dr Marcus Steiner, once Chief Scientist of the Terran Bureau of Investigation, possessed the knowledge and skills that, unfortunately, were needed now.

Back on Earth, his friends had often asked him why he had chosen to become a professor of criminology. And he had always given the same answer: ‘The only alternative was to become a criminal.”

It had taken Steiner almost a week to modify the sickbay’s standard encephalographic equipment and to check the computer programs. Meanwhile, the four Sabras remained confined to their quarters and stubbornly refused to make any admission of guilt.

Owen Fletcher did not look very happy when he saw the preparations that had been made for him; there were too many similarities to electric chairs and torture devices from the bloodstained history of earth. Dr Steiner quickly put him at ease with the synthetic familiarity of the good interrogator.

“There’s nothing to be alarmed at, Owen — I promise you won’t feel a thing. You won’t even be aware of the answers you’re giving me — but there’s no way you can hide the truth. Because you’re an intelligent man, I’ll tell you exactly what I’m going to do. Surprisingly enough, it helps me do my job; whether you like it or not, your subconscious mind will trust me — and cooperate.”

What nonsense, thought Fletcher; surely he doesn’t think he can fool me as easily as that! But he made no reply, as he was seated in the chair and the orderlies fastened leather straps loosely around his forearms and waist. He did not attempt to resist; two of his largest ex-colleagues were standing uncomfortably in the background, carefully avoiding his eye.

“If you need a drink or want to go to the toilet, just say so. This first session will take exactly one hour; we may need some shorter ones later. We want to make you relaxed and comfortable.”

In the circumstances, this was a highly optimistic remark, but no one seemed to think it at all funny.

“Sorry we’ve had to shave your head, but scalp electrodes don’t like hair. And you’ll have to be blindfolded, so we don’t pick up confusing visual inputs… Now you’ll start getting drowsy, but you’ll remain conscious… We’re going to ask you a series of questions which have just three possible answers — Yes, No, Don’t Know. But you won’t have to reply; your brain will do it for you, and the computer’s trinary logic system will know what it’s saying.

“And there’s absolutely no way you can lie to us; you’re very welcome to try! Believe me, some of the best minds of Earth invented this machine — and were never able to fool it. If it gets ambiguous answers, the computer will simply reframe the questions. Are you ready? Very well… Recorder on high, please… Check gain on Channel 5… Run program.”

YOUR NAME IS OWEN FLETCHER… ANSWER YES… OR NO…

YOUR NAME IS JOHN SMITH… ANSWER YES… OR NO…

YOU WERE BORN IN LOWELL CITY, MARS… ANSWER YES…OR NO….

YOUR NAME IS JOHN SMITH… ANSWER YES… OR NO…

YOU WERE BORN IN AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND… ANSWER YES… OR NO…

YOUR NAME IS OWEN FLETCHER…

YOU WERE BORN ON 3 MARCH 3585…

YOU WERE BORN ON 31 DECEMBER 3584…

The questions came at such short intervals that even if he had not been in a mildly sedated condition, Fletcher would have been unable to falsify the answers. Nor would it have mattered had he done so; within a few minutes, the computer had established the pattern of his automatic responses to all the questions whose answers were already known.

From time to time the calibration was rechecked (YOUR NAME IS OWEN FLETCHER… YOU WERE BORN IN CAPETOWN, ZULULAND…), and questions were occasionally repeated to confirm answers already given. The whole process was completely automatic, once the physiological constellation of YES — NO responses had been identified.

The primitive ‘lie detectors’ had tried to do this with fair success — but seldom complete certainty. It had taken no more than two hundred years to perfect the technology and thereby to revolutionize the practice of law, both criminal and civil, to the point when few trials ever lasted more than hours.

It was not so much an interrogation as a computerized — and cheat-proof— version of the ancient game Twenty Questions. In principle, any piece of information could be quickly pinned down by a series of YES — NO replies, and it was surprising how seldom as many as twenty were needed when an expert human cooperated with an expert machine.

When a rather dazed Owen Fletcher staggered from the chair, exactly one hour later, he had no idea what he had been asked or how he had responded. He was fairly confident, however, that he had given nothing away.

He was mildly surprised when Dr Steiner said cheerfully, “That’s it, Owen. We won’t need you again.”

The professor was proud of the fact that he had never hurt anybody, but a good interrogator had to be something of a sadist — if only a psychological one. Besides, it added to his reputation for infallibility, and that was half the battle.

He waited until Fletcher had regained his balance and was being escorted back to the detention cell.

“Oh, by the way, Owen — that trick with the ice would never have worked.”

In fact, it might well have done; but that didn’t matter now. The expression on Lieutenant Fletcher’s face gave Dr. Steiner all the reward he needed for the exercise of his considerable skills.

Now he could go back to sleep until Sagan 2. But first he would relax and enjoy himself, making the most of this unexpected interlude.

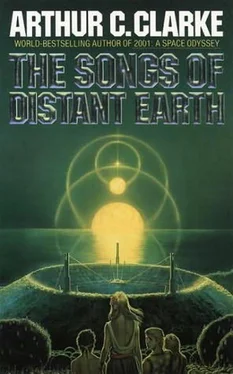

Tomorrow he would have a look at Thalassa and perhaps go swimming off one of those beautiful beaches. But for the moment he would enjoy the company of an old and beloved friend.

The book he drew reverently out of its vacuum-sealed package was not merely a first edition; it was now the only edition. He opened it at random; after all, he knew practically every page by heart.

Читать дальше