“That’d be great, sweetheart, but your Ma would say I was tempting Kali,” Doc said, ducking his head and rubbing his smeary cheek against hers. Rama Joan smiled fondly at him as she pulled her daughter out giggling.

“No water in the dip,” Hunter called back. At that moment his legs went out from under him and he sat down. “But it’s damn slippery,” he qualified as he scrambled to his feet, Margo grinning at him unfeelingly. “This film of wet ash is treacherous.”

Rama Joan’s smile faded. From beside the Corvette she whispered urgently to Doc, “Can’t we fill the dip with stones and earth, or at least clean it off?”

He leaned toward her and answered in a low, fast voice: “Look, darling, those murdering drunken kids are bound to get some cars on this road soon and come whooping for the beach. A lot of them have been doing it all their lives. Second nature to them. We really haven’t a minute to lose.”

He sat back, honked the horn once and roared the motor. “Here I come!” he warned.

He drove fast and the Corvette jounced through the dip with no sideslip at all. He parked it well ahead, then came jog-trotting back to where Rama Joan, Margo and Hunter were standing above the dip. Ann was back by the bus, chattering to McHeath and admiring his rifle.

“That was a rousing anticlimax,” Doc said. “I guess I’m getting chicken in my old age.” Hunter and Margo laughed. Rama Joan smiled uncertainly.

Ida called thinly from beside the truck: “Mr. Brecht! Ray Hanks doesn’t want to be lifted out again.”

Doc looked around at the others, shrugged, said: “It’ll save time,” and yelled: “O.K., let him chance it! Bring it over, Hixon!”

The truck got off to a fast start, too. Only as it jounced by them safely did they see that Mrs. Hixon was in back, braced over Hanks and holding on to the side across the cot.

The school-bus passengers came trudging across: the Ramrod, Wanda — and Ida with them — but not Wojtowicz, who’d stopped by McHeath and Ann; finally Clarence Dodd and Pop arguing together, the latter protesting.

Doc pulled his doubly black hat down on his forehead and headed toward them briskly. “I know, I know!” he said as Pop opened his ill-toothed mouth at him. “The back tires are slicker than ever…and so forth. Leave it to Hotrod Rudy.”

“One cylinder’s missing, too,” Pop called after him, but Doc just kept on going toward the bus.

Clarence Dodd took note of Margo’s and the others’ blackened faces. “That shower would have delighted Charles Fort,” he said, smiling. “You look as if you were all getting ready for an Indian funeral.”

Margo thought for the first time since last night of the tortured girl in her tomb up the slope.

Rama Joan suddenly started back toward the school bus after Doc. Ann waved to her from beside him. “Hi, Mommy!” Rama Joan stopped and waved back uncertainly.

Ann giggled, and McHeath and Wojtowicz laughed at something Doc said as he climbed aboard the bus. The motor coughed into life and it came on, gathering speed but then hesitating.

Pop muttered: “She sometimes balks shifting into second.”

The bus entered the dip very slowly. Its front wheels hesitated coming out, and then its rear end began to slide swiftly sideways. Doc gunned the motor. The back tires wailed against the black-slimed stone. Doc cut the wheels and braked. The bus slid backward down the slope.

McHeath shoved his rifle into Wojtowicz’s hands and ran down across the rock toward the bus, his feet hitting potholes and tiny ridges.

The bus hesitated, then paused on the verge of the five-hundred-foot drop with one front wheel against a small rock in a pothole. They could all see Doc pulling himself out of the backward-tilted seat, bracing himself on the slanted floor, and grabbing for the lever that opened the front door.

Hunter suddenly grabbed Margo by the shoulder, thrust his hand in her jacket, and pulled out the momentum pistol.

McHeath was almost to the bus and near the verge himself. Wojtowicz wondered what the kid thought he could do: maybe, he guessed, brace himself and offer a hand to steady Doc when he jumped down onto the slippery slope.

Doc got the door open and his head out of it. Then the little rock popped out of the pothole and the back wheels of the bus slid over the edge, the floor slanting still more against Doc’s escape effort, and the underbody grated harshly on the rock lip as it slowly slid over.

Hunter squeezed the tiny recessed lever on top of the grip of the gray pistol between his finger and thumb and twisted it around so that the arrow pointed not toward the muzzle but away from it.

Doc had his upper body out of the door when the bus overbalanced, setting him back on his heels in the door. As the bus swung out and down with him in it, he looked at his friends up the slope and took off the black hat and waved it.

Hunter pointed the momentum pistol at him and pressed the button.

Doc’s face dropped out of sight and his upstretched hand too, but the black hat came sailing back over the lip, and a chill breeze with it.

McHeath threw himself down on the verge, gripping a rock ridge with foot, knee, elbow, and hand, and peered over.

The slope vibrated faintly underfoot and the big crash came hollowly.

The chill breeze quickened. The black hat sailed straight at Hunter and hung itself on the muzzle of the momentum pistol. A small boulder started to roll uphill after it. Hunter nipped his finger off the button and bowed his head. The small boulder reversed course and rolled down the slope, clinking.

McHeath called hoarsely, his voice cracking halfway through: “He’s gone. He was thrown out. I saw him hit. Then the bus rolled over him.”

Hunter said: “Just one second sooner…”

Clarence Dodd said to him: “You switched the arrow one hundred and eighty degrees, and it reversed the momentum?” And when Hunter nodded heavily, the Little Man commented: “Well, that’s logical.”

Hunter snatched the black hat off the muzzle and swung it up as if to throw it down and stamp on it. Then he just looked at it in his hand.

There was a faint hollow crack as the small boulder hit five hundred feet below and the sound came up.

On the sunbeaten mesa in Arizona, as if it were a Parsi Tower of Silence, vultures tore away the last shreds of the flesh of Asa Holcomb’s face, laying wholly bare the beautiful grinning red bone.

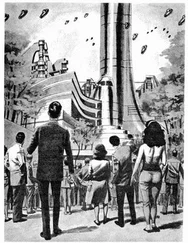

Paul Hagbolt rested lightly against the warm, smooth, trusty window that half spanned Tigerishka’s saucer. He gazed down at Earth’s northern ice cap breaking up, the white crust of frozen water lifted and collapsed by the great tides that had been moving in and out through the Greenland Sea, Baffin Bay, and the Bering Strait. Almost the whole Arctic zone was out of shadow, as Earth’s summering northern hemisphere tilted toward the sun.

The interior of the saucer was dark, but some light was reflected into it by the snow-freighted ice, which twinkled with highlights wherever ice-tables tilted to reflect the sun directly — stars in a white sky.

Tigerishka was stretched out against the window, too, a few feet from Paul. She was caressing Miaow, but now the little cat drew away from the velvet-padded, three-fingered hand and bent her hind legs against the violet-barred, green-furred shoulder, and sprang off across Paul into the flowerbank beyond him — presumably to re-explore it by the mysterious ice-sent twilight. Miaow had adapted quickly to free fall and delighted in worming her way through the plants along the thick vines, her tiny face cat-smiling out between the leaves and flowers from time to time.

Tigerishka made a quick, soft singing sound that was rather like a sigh. It occurred to Paul that she might have brought them here to escape the reproachful thought of people dying as they looked down at Earth. He almost started to tell her that there was, or yesterday had been, a Russian weather station at the North Pole, but decided she could read that in his thoughts if she wanted to.

Читать дальше