A word jumped up in his mind: antigravity. If this vehicle carried its own null-gravity field — possibly null-inertia too — that could explain the absence of any felt G-forces, and also his floating, dripping wet, surrounded by floating round drops of this wetness, in breathable perfumy air in a round, flattened room lined with live flowers.

Claws stung his left hand like a dozen wasps: Miaow was terrified by the strange jolts, and insulted by sea water, and she held on to him overtightly. In his sudden agony Paul flung off the soaking cat, and she shot twisting through the air and vanished with a puff of yellow-pink petals into a flowerbank.

The next instant he was grabbed from behind and slammed flat on his back against a hard, satin-smooth surface that had somehow been somewhere in the omni-surrounding flowers. The thing that terrified him most was that the limb that snaked around his neck — a sleek, spring-strong, green-furred limb, barred with violet — had two elbows.

With a whirling speed that did not allow his seeing it clearly, the green and violet tiger-thing worked at his out-flung wrists and ankles. Paws with claws of violet-gray pinched without stabbing; once he felt the grip of something more like a snake. Then the thing kicked off from his side and dived into the flowerbank after Miaow. A long green violet-ringed tail, smoothly furred and tapering, vanished in a larger explosion of petals.

He tried to push himself up from the surface under him and discovered he could budge only his head. Though still in null gravity, he was somehow gyved tautly to that same surface — as was next brought home to him most graphically when he looked straight up and saw not ten feet above him (or below, or out to the side — he didn’t know how to feel about it in null gravity) a spread-eagled, wet-sand-specked, pale, wildly staring reflection of himself, backed by a dozen dimming reflections of reflections of the same ridiculous, poignant picture.

The inner shape and decor of the saucer began to come clear to him. More than half the flowers he’d seen had been reflections. Ceiling and floor were round, flat mirrors facing each other, about nine feet apart and twenty feet in diameter. He was spread-eagled near the center of one of them. The rim between the mirrors was luxuriant with exotic, thick-petaled flowers, large and small — pale yellow, pale blue, violet, magenta, but mostly pink and pinkish red. Seemingly live flowers, for there were leaves shaped like sickles and swords and spears, and there were glimpses of twisting branches — probably their hydroponic or whatever underpinnings filled much of the saucer’s tapered outside rim.

But the triangularly cross-sectioned doughnut of the rim couldn’t be entirely filled with vegetation, for bowered in it beyond his fettered feet he now made out a silvery gray control panel — at any rate some sort of flat surface with smooth silvery excrescences and geometrical shapes limned on it. Straining his head around, he could see similar panels beyond each of his spread and outstretched arms, the three panels being situated relative to each other at the apices of an equilateral triangle incribed in the saucer, but each of them half hidden by the embowering flowers — very much as crassly functional objects such as heater and sink and phone and hi-fi might be masked in the small apartment of a modish and esthetically-minded woman.

The whole was bathed in bright, warm, beachy light coming from…he couldn’t see where. An invisible indoor sun — most eerie.

Eerier still and infinitely closer to home was the feeling that next came to him: that his mind was being invaded and his memories and knowledge riffled through like so many decks of cards. He tritely recalled how a drowning man is supposed to relive his life in a few seconds, and he wondered if it applied when you drowned in flowers — or were crucified by a tiger preparatory to being torn apart and devoured.

The sensations in his mind flashed so fast he could see and hear only blurs. They were his own private mental possessions, yet he was unable to note them as they flashed and faded — an ultimate humiliation! A few images he was able to catch toward the end of this mental “customs search” showed an odd preoccupation with zoos and ballets.

He looked around but could catch no glimpse of the tiger-thing or of Miaow. The invisible sun radiated on. The flower-banks were deathly still, exuding their perfumes.

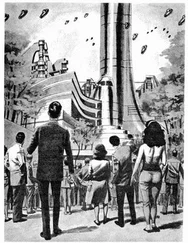

Donald Merriam was midway in his third passage through the Wanderer’s shadow. To his right was the strange planet’s green-spotted night side, which still made him think of a spider’s underbelly. Ahead lay the sheaf of stars, and to his left the black, ever-lengthening ellipsoid of the moon with the cobwebby black threads looping up from its nose against the thickly glittering background. He was beginning to feel tired and cold, and he’d quit working the radio.

A dim, yellowish point appeared against the Wanderer’s face, ahead, near the star-sheaf. It rapidly became a yellowish dash, horizontal to him, then a double dash with a little black stretch in the middle like the popular new fluorescent auto headlights, then two yellowish spindles that grew in size.

Only then did Don realize that this wasn’t some sort of surface appearance on the Wanderer, but a material something — or two things — headed straight at the Baba Yaga. He flinched and blinked his eyes, and the next instant, without any gradual deceleration that he could note, the two yellow spindles had come to a dead stop to either side of the Baba Yaga and so close that the frame of the spacescreen chopped off the outer dagger-end of each spindle.

They looked to him now like two saucer-shaped spacecraft between thirty and fifty feet across and three or four yards thick. At least, he rather hoped they were spacecraft — and not, well, animals.

His estimate of their shape was confirmed when, without any visible flash of vernier jets, they tilted toward him and became two yellow circles, one with a violet triangle inscribed in it, the other with a violet V, the legs of which stretched from center to rim.

Then he felt his spacesuited body pushed gently backward as the Baba Yaga was drawn forward between its escorts — that was how he began to think of them — until only the forward edges of their rims showed in the spacescreen. They held position very precisely thereafter, as if they had locked onto his little moonship — and somehow onto his body too, a very strange sensation.

The next thing he noticed was that the pale green spots were crawling down the Wanderer’s black rotundity as if they were so many phosphorescent sow-bugs!

Then he saw that the sheaf of stars was widening as the black ellipsoid of the moon dropped away.

From all indications the Baba Yaga was being drawn upward by its escorts at about one hundred miles a second. Yet he had not felt an atom of the G-forces that ought to have been crushing him against his ship’s wall — or smashing him through it!

At no time in the past few hours, not even during his passage through the moon, had Don thought, This must be an hallucination. He thought it now. Acceleration and the price you paid for it in fuel and G-strains were the core of his professional knowledge. What was happening to his body and to the Baba Yaga now was not merely a monstrous intrusion of the unknown, it flatly contradicted everything he knew about spaceflight and its iron limitations. From five miles a second, Wanderer-relative, to one hundred at right angles to the first course, yet without feeling it, without even the hint of the firing of some main jet hotter than a blue star — that was not merely weird, it was impossible!

Yet the green spots continued to scuttle out of sight below and the star-sheaf to widen above, and suddenly the Baba Yaga burst into sunlight above the Wanderer. Reflected glare stabbed at his eyes from the lefthand side of the spacescreen frame and the yellow rim of his port escort. He squeezed his eyelids together, fumbled for the polarizing goggles, got them on, then opened his eyes and looked.

Читать дальше