“It gets lonely, doesn’t it?” Rama Joan said softly, “when you cut yourself off from the big protector and throw in your lot — and your girl friend’s — with a bunch of nuts, just to attend a dog’s funeral.”

They were walking at the tail end of the procession, well behind the cot borne between Clarence Dodd and Wojtowicz.

Paul had to chuckle. “You’re frank about it,” he said. “Margo’s not my girl friend, though — I mean the feeling’s all on my side. We’re really just friends.”

Rama Joan looked at him shrewdly. “So? A man can waste his life on friendship, Paul.”

Paul nodded unhappily. “Margo’s told me that herself,” he said. “She claims I get my satisfaction out of mother henning her around and trying to keep other men away from her. Except for Don, of course — and she thinks my interest in him is more than brotherly, even if I don’t know it.”

Rama Joan shrugged. “Could be, I suppose. The set-up of you and Margo and Don does seem unnatural.”

“No, it’s perfectly natural in its way,” he assured her with a kind of gloomy satisfaction. “The three of us went to high school and college together. We were interested in science and things. We meshed. Then Don went on to become an engineer and a spaceman, while I took the turn into journalism and PR work, and Margo into art.

But we were determined to stick together, so when Don got into the Moon Project, we managed to, too, or at least I did. By that time Margo had decided she liked him a little better than she did me — or loved him, whatever that means — and they got engaged. So that was settled — maybe simply because our society frowns on triangular living arrangements. Then Don went to the moon. We stayed on Earth. That’s all there is to it, until this evening, when I seem to have thrown in with you people.”

“Maybe because you had an explosion overdue. Well, I can tell you why I’m here,” the red-blonde woman continued. “I could be safe in Manhattan, an advertising executive’s wife: Ann going to a fancy school, myself fitting in an occasional lecture on mysticism to a women’s club. Instead, I’m divorced, eking out a tiny inherited income with lecture fees, and dressing up the mysticism with all sorts of carnival hokum.” She indicated her white tie and tails with a disparaging laugh. ” ‘Masculine protest’, my friends said. ‘No, just human protest’, I told them. I wanted to be able to say things I really meant and say them to the hilt — things that were mine alone. I wanted Ann to have a real mother, not just a well-dressed statistic.”

“But do you really mean the things you say?” Paul asked. “Buddhism, I gather — that sort of thing?”

“I don’t believe them as much as I’d like to, but I do believe them as much as I can,” she told him. “Certainty’s a luxury. If you say things with gusto and color, at least you’re an individual. And even if you fake it a bit, it’s still you, and if you keep trying you may some day come out with a bit of the truth — like Charlie Fulby did, when he told us he knew about his wild planets not by flying-saucer trips, as he’d always claimed, but by pure intuition.”

“He’s paranoid,” Paul muttered, gazing ahead at the Ramrod where he marched behind the cot, with Wanda to his right and the thin woman to his left. “Are those two women his disciples, or patrons, or what?”

“I’m sure he is somewhat paranoid,” Rama Joan said, “but you surely don’t believe, do you, Paul, that sane people have a monopoly of the truth? No, I think they’re his wives — he grew up in a complex-marriage sect. Oh, Paul, you do find us alarming, don’t you?”

“Not really,” he protested. “Though there’s something reassuring about moving with the majority.”

“And with the money and the power,” Rama Joan agreed. “Well, cheer up — the majority and the nuts spend most of their time the same way: satisfying basic needs. We’re all going back to the pavilion on the beach simply because we think there’ll be coffee and sandwiches.”

At the head of the procession, Hunter was telling Margo Gelhorn very much the same sort of thing. “I started going to flying-saucer meetings as a sociological project,” he confessed to her. “I went to all kinds: the way-out contactees like Charlie Fulby, the sober-minded ones, and the in-between-ers and freewheelers, like this group. I wanted to analyze a social syndrome and write a few papers on it. But after a while I had to admit I was keeping on going because I was hooked.”

“Why, Professor Hunter?” Margo asked, hugging Miaow to her. She was cold without her jacket, and the cat was like a hot water bottle. “Does saucering make you feel bohemian and different, like wearing a beard?”

“Call me Ross. No, I don’t think so, though I suppose vanity plays a part.” He touched his beard. “No, it was simply because I’d found people who had something to follow and be excited about, something to be disinterestedly interested in — and that’s not so common any more in our money-and-sales-and-status culture, our don’t-give-yourself-away yet sell-yourself-to-everybody society. It got so I wanted to make a contribution of my own — the lecturing and panel bits. Now I do almost as much saucering as Doc, who knocks himself out selling pianos — he’s a whiz at that — so he can divide the rest of his time between saucering, chess, and living it up.”

“But Doc’s a bachelor, while I believe you implied you had a family…Ross?” Margo pointed out with faint malice.

“Oh yes,” Hunter conceded a bit wearily. “Up in Portland there’s a Mrs. Hunter and two boys who think Daddy spends altogether too much time consorting with saucer bugs, considering the very few papers he’s got out of it and the nothing it’s done for his academic reputation.”

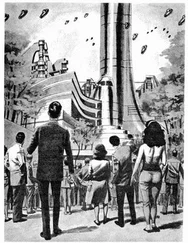

He was thinking of adding: “And, right now, they’re sitting up asking why Daddy wasn’t home the night the heavens changed and saucers came true” — but just then he realized they’d reached the boarded-up beach house and the old dance floor. There was the green lantern, he saw, still burning, and beside it a chair with a little stack of unused programs, and there were the empty chairs sitting in rows, though with the first rows much disarranged (when would Doddsy ever reclaim the deposit they’d made on them at the Polish funeral parlor in Oxnard?) — and there was a coat someone had forgotten laid over one of the chairs, and there was the panelists’ long table and under it some cardboard boxes they’d left in their hurry. And thrust deep into the sand nearby there was even the big furled umbrella Doc had used as part of a crude astrolabe when first checking the movement of the Wanderer.

As Ross Hunter saw these things standing out against the purple-gold-speckled, spectrally calm Pacific, he felt a great, unexpected surge of affection and nostalgia and relief, and he suddenly realized why, after being rebuffed by a landslide and a steel mesh fence and a red-tape major, they had trudged back to this spot.

It was simply that it was home to them, the spot where they’d been together in security and where they’d witnessed the change in the heavens, and that each of them knew in his heart that this might be the last home any of them would ever have.

Without haste Wanda and the thin woman and young Harry McHeath made for the boxes under the table.

Wojtowicz and the Little Man set down the cot with Ragnarok on it, half shrouded by Margo’s jacket.

Wojtowicz looked around, then pointed at the umbrella and said in a firm voice: “I somehow think that would be the right spot — that is, if you wouldn’t mind?” he added to Doc, who’d walked silently all the way from Vandenberg Two beside the Little Man.

Читать дальше