“Valben, Valben, Valben!”

“What do you want with me? Why won’t you leave me alone?”

“Valben, boy—”

Lawler realized suddenly that he could no longer see the tall shadowy figure.

“Where are you?”

“Everywhere around you, and nowhere.”

Lawler’s head was throbbing. Something was churning in his stomach. He groped in the dark for his numbweed flask. After a moment he remembered that it was empty.

“ What are you?”

“I am the resurrection and the life. He that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.”

“No!”

“God save thee, ancient Mariner! From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—”

“This is lunacy! Stop it! Get out of here! Out!” Trembling now, Lawler searched for his lamp. Light would drive this thing away. But before he could locate it he felt a sudden sharp sense of new solitude and realized that the vision, or whatever it had been, had left him of its own accord.

Its departure left an unexpected ringing emptiness behind.

Lawler felt its absence as a shock, like that of an amputation. He sat for a time at the edge of his bunk, shivering, sweat-soaked, shaking as he had shaken during the worst of his period of withdrawal of the drug.

Then he rose. Sleep wasn’t likely now. He went up on deck. A couple of moons were overhead, stained strange purples and greens by the luminescence that rose out of the western horizon and now seemed to fill the air all the time. The Hydros Cross itself, hanging off in the corner of the sky like a bit of discarded finery, was pulsing in colour too, something Lawler had never seen before: from its two great arms came booming, dizzying swirls of turquoise, amber, scarlet, ultramarine.

Nobody seemed to be on duty. The sails were set, the ship was responding to a light steady breeze, but the deck looked empty. Lawler felt a quick stab of terror at that. The first watch should be on duty: Pilya, Kinverson, Gharkid, Felk, Tharp. Where were they? Even the wheel-box was untended. Was the ship steering itself?

Apparently so. And steering off course, too. Last night, he remembered now, the Cross had been off the port bow. Now it was lined up with the beam. They were no longer going west-southwest, but had swung around at a sharp angle to their former path.

He tiptoed around the deck, mystified. When he came by the rear mast he saw Pilya asleep on a pile of ropes, and Tharp nearby, snoring. Delagard would flay them if he knew. A little farther on was Kinverson, sitting against the side with his back to the rail. His eyes were open, but he didn’t seem awake either.

“Gabe?” Lawler said quietly. He knelt and waggled his fingers back and forth in front of Kinverson’s face. No response. “Gabe, what’s going on? Are you hypnotized?”

“He’s resting,” came the voice of Onyos Felk suddenly, from behind. “Don’t bother him. It was a busy night. We were hauling sail for hours and hours. But look now: there’s the land, dead ahead. We’re moving very nicely toward it.”

Land? When did anyone ever speak of land, on Hydros?

“What are you talking about?” Lawler asked.

“There. Do you see it?”

Felk gestured vaguely toward the bow. Lawler looked forward and saw nothing, just the vastness of the luminous sea, and a clear horizon marked only by a few low stars and a sprawling, heavy cloud at middle height. The dark backdrop of the sky seemed weirdly ablaze, a frightful aurora fiercely blazing. There was colour everywhere, bizarre colour, a fantastic show of strange light. But no land.

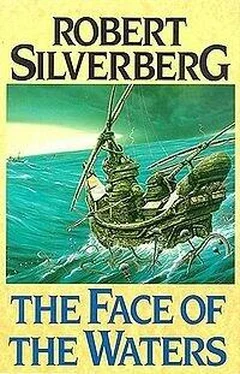

“In the night,” said Felk, “the wind shifted, and turned us toward it. What an incredible sight it is! Those mountains! Those tremendous valleys! Would you ever have believed it, doc? The Face of the Waters!” Felk seemed about to burst into tears. “All my life, staring at my sea-charts, seeing that dark mark on the far hemisphere, and now we’re looking it right in the eye—the Face, doc, the Face itself!”

Lawler pulled his arms close against his sides. In the tropic warmth of the night he felt a sudden chill.

He still saw nothing at all, only the endless roll of the empty water.

“Listen, Onyos, if Delagard comes on deck early and finds your whole watch sleeping, you know what’s going to happen. For God’s sake, if you won’t wake them up, I will!”

“Let them sleep. By morning we’ll be at the Face.”

“What Face? Where?

“There, man! There!”

Lawler still didn’t see. He strode forward. When he reached the bow he found Gharkid, the one missing member of the watch, sitting crosslegged, perched on top of the forecastle with his head thrown back and his eyes wide and staring like two orbs of glass. Like Kinverson he was in some other state of awareness entirely.

Bewilderedly Lawler peered into the night. The dazzling maze of colours danced before him, but he still saw only clear water and empty sky ahead. Then something changed. It was as though his vision had been clouded, and now at last it had cleared. It seemed to him that a section of the sky had detached itself and come down to the water’s surface and was moving about in an intricate way, folding and refolding upon itself until it looked like a sheaf of crumpled paper, and then like a bundle of sticks, and then like a mass of angry serpents, and then like pistons driven by some invisible engine. A writhing interwoven network of some incomprehensible substance had sprung up along the horizon. It made his eyes ache to watch it.

Felk came up alongside him.

“Now do you see? Now?”

Lawler realized that he had been holding his breath a long while. He let it out slowly.

Something that felt like a breeze, but was something else, was blowing toward his face. He knew it couldn’t be a breeze, for he could feel the wind also, blowing from the stern, and when he glanced up at the sails he saw them bellying outward behind him. Not a breeze, no. An emanation. A force. A radiation. Aimed at him. He felt it crackling lightly through the air, felt it striking his cheeks like fine wind-blown hail in a winter storm. He stood without moving, assailed by awe and fear.

“Do you see?” Felk said again.

“Yes. Yes, now I do.” He turned to face the mapkeeper. By the strange light that was bursting upon them from the west Felk’s face seemed painted, goblinish. “You’d better wake up your watch, anyway. I’m going to go down below and get Delagard. For better or for worse, he’s brought us this far. He doesn’t deserve to miss the moment of our arrival.”

In the waning darkness Lawler imagined that the sea that lay before them was retreating swiftly, pulling back as though it were being peeled away, leaving a bare, bewildering sandy waste between the ship and the Face. But when he looked again he saw the shining waters as they had always been.

Then a little while later dawn arrived, bringing with it strange new sounds and sights: breakers visible, the crisp slap of wavelets against the bow, a line of tossing luminous foam in the distance. By the first grey light Lawler found it impossible to make out more than that. There was land ahead, not very far, but he was unable to see it. All was uncertain here. The air seemed thick with mist that would not burn off even as the sun moved higher. Then abruptly he became aware of the great dark barrier that lay across the horizon, a low hump that might almost have been the coastline of a Gillie island, except that there weren’t any Gillie islands the size of this one on Hydros. It stretched before them from one end of the world to the other, walling off the sea, which thundered and crashed against it in the distance but could not impose its strength on it in any way.

Delagard appeared. He stood trembling on the bridge, face thrust forward, hands gripping the rail in eerie fervour.

Читать дальше