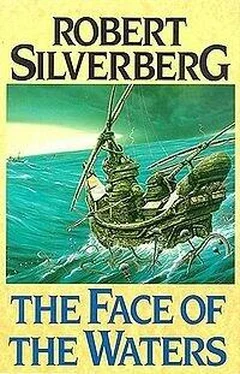

Robert Silverberg - The Face of the Waters

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Silverberg - The Face of the Waters» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: Grafton Books, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Face of the Waters

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grafton Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-246-13718-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Face of the Waters: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Face of the Waters»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Face of the Waters — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Face of the Waters», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Lawler sat back for a moment, trying to think.

He turned Martello over again and picked up his scalpel.

“You won’t want to see this,” Lawler said to anyone who might be watching, without looking up, and drew a red line with the sharp iron point from left to right across Martello’s abdomen. Martello barely seemed to notice. He made a soft blurry sound, the vaguest of comments. Other distractions were taking priority for him.

Skin. Muscle. The knife seemed to know where it had to go. Deftly Lawler stripped back the layers of tissue. He was cutting now through the peritoneum. He had trained himself to enter an altered state of consciousness whenever he performed surgery, in which he thought of himself as a sculptor, not as a surgeon, and of the patient as something inanimate, a wooden log, not a suffering human being. That was the only way he could bear the process at all.

Deeper. He had breached the restraining abdominal wall, now. Blood mingled with the puddle of seawater around Martello on the deck.

The intestinal coils should come spilling out into view—

Yes. Yes. There they were.

Someone screamed. Someone uttered a grunt of disgust.

But not at the sight of the intestines. Something else was rising from Martello’s belly, something slender and bright, slowly unreeling itself and standing up on end. Perhaps six centimetres of it was visible: eyeless, seemingly even headless, just a smooth, slippery pink strip of undifferentiated living matter. There was an opening at its top end, a mouth of sorts, through which a sharp little rasping red tongue could be seen. The supple shining creature moved with supernal grace, gliding from side to side in a hypnotic way. Behind Lawler the screaming went on and on.

He struck the thing with a quick, steady backhand flick of his scalpel that cut it neatly in half. The upper end landed on the deck next to Martello, writhing. It began heading toward Lawler. Kinverson’s great boot descended at once and crushed it to slime.

“Thanks,” Lawler said quietly.

But the other half was still inside. Lawler tried to coax it out with the scalpel’s tip. It seemed untroubled by its bisecting; its dance continued, as graceful as before. Probing behind the heavy mound of intestines, Lawler struggled to dislodge it. He poked here, tugged there. He thought he saw the inner end of it and sliced at it, but there was more: another few centimetres still mocked him. He cut again. This time he had it all. He flipped it aside. Kinverson crushed it.

Everyone was silent now behind him.

He started to close the incision. But a new squirming motion made him stop.

Another one? Yes. Yes, one more, at least. Probably others. Martello groaned. He stirred slightly. Then he jerked with sudden force, rising a little way from the deck: Lawler got the scalpel out of the way just in time to keep from wounding him. A second eel rose into view and a third, weaving in that same eerie dance; then one of them pulled itself back in and disappeared once again into Martello’s abdominal cavity, burrowing upward in the general direction of his lungs.

Lawler teased the other one out, cut it in half and in halves again, yanked the last bit of it free. He waited for the one that had gone back in to make itself visible again. After a moment he caught a glimpse of it, bright and gleaming within Martello’s bloody midsection. But it wasn’t the only one. He could see the slender coils of others, now, busily wriggling about, having themselves a feast. How many more were in there? Two? Three? Thirty?

He looked up, grim-faced. Delagard stared back at him. There was a look of shock and dismay and sheer revulsion in Delagard’s eyes.

“Can you get them all out?”

“Not a chance. He’s full of them. They’re eating their way through him. I can cut and cut, and by the time I’ve found them all I’ll have cut him to pieces, and I still won’t have found them all, anyway.”

“Jesus,” Delagard murmured. “How long can he live this way?”

“Until one of them reaches his heart, I suppose. That won’t be long.”

“Can he feel anything, do you think?”

“I hope not,” Lawler said.

The agony went on another five minutes. Lawler had never realized that five minutes could last so long. From time to time Martello would jump and twitch as some major nerve was struck; once he seemed to be trying to rise from the deck. Then he uttered a little sighing sound and fell back, and the light went out of his eyes.

“All over,” Lawler announced. He felt numb, hollow, weary, beyond all grief, beyond all shock.

Probably, he thought, there had never been any chance to save Martello. At least a dozen of the eels must have entered him, very likely more, a horde of them gliding swiftly in through mouth or anus and burrowing diligently through flesh and muscle toward the centre of his abdomen. Lawler had extracted nine of the things; but others were still lurking in there, at work on Martello’s pancreas, his spleen, his liver, his kidneys. And when they were done with those, the delicacies, there was all the rest of him awaiting their little rasping red tongues. No surgery, no matter how speedily done or unerring, could have cleaned all of them out of him in time.

Neyana brought a blanket and they wrapped it about him. Kinverson gathered the body in his arms and moved toward the side with it.

“Wait,” Pilya said. “Put this with him.”

She held a sheaf of papers that she must have brought up from Martello’s cabin. The famous poem. She tucked the worn and folded pages of the manuscript into the blanket and pulled its ends tight around the body. Lawler thought for a moment of objecting, but he checked himself. Let it go. It belonged with him.

Quillan said, “Now we commend our dearly beloved Leo to the sea, in the name of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost—”

The Holy Ghost again? Every time Lawler heard that odd phrase of Quillan’s he was startled by it. It was such a strange concept: try as he might, he couldn’t imagine what a holy ghost might be. He shook the thought away. He was too tired for such speculations now.

Kinverson carried the body to the rail and held it aloft. Then he gave it a little push and it went outward, downward, into the water.

Instantly creatures of some strange kind appeared as if by a conjuring spell from the depths, long slim finny swimmers covered in thick black silken fur. There were five of them, sinuous, gentle-eyed, with dark tapering snouts covered with twitching black bristles. Gently, tenderly, they surrounded Martello’s drifting body and buoyed it up and began to unwrap the blanket that covered it. Tenderly, gently, they pulled it free. And then—gently, tenderly—they clustered around his stiffening form and set about the task of consuming him.

It was quietly done, no slovenly gluttonous frenzy. It was horrifying and yet eerily beautiful. Their motions stirred the sea to extraordinary phosphorescence. Martello seemed to be absorbed by a shower of cool crimson flame. Slowly he exploded in light. They made an anatomy lesson of him, peeling back the skin with utmost fastidiousness to reveal tendons, ligaments, muscles, nerves. Then they went deeper. It was a profoundly disturbing thing to watch, even for Lawler, to whom the inner secrets of the human body were no secret at all; but nevertheless the work was carried out so cleanly, so unhurriedly, so reverently, that it was impossible not to watch, or to fail to see the beauty in what they were doing. Layer by layer they put Martello’s core on display, until at last only the white cage of bone remained. Then they looked up at the watchers at the rail as though for approval. There was the unmistakable glint of intelligence in their eyes. Lawler saw them nod in what could only have been a salute; and then they slipped out of sight as silently as they had come. Martello’s clean skeleton had already disappeared, on its way to some unknown depth where, no doubt, other organisms were waiting to put its calcium to good use. Of the vital young man who had been Leo Martello nothing was left now except some pages of manuscript drifting on the surface of the water. And after a little while not even those could be seen.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Face of the Waters»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Face of the Waters» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Face of the Waters» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.