Delagard sniffed. “You stink like a Gillie. What were you doing, letting them fuck you?”

“You guessed it. You ought to try it. You might learn a thing or two.”

“Very funny. But you do stink of Gillie, you know. Did they try to rough you up?”

“One of them brushed against me as I was leaving,” Lawler said. “I think it was an accident.”

Shrugging, Delagard said, “All right. You get anywhere with them?”

“No. Did you really think I would?”

“There’s always hope. A gloomy guy like you may not think so, but there always is. We’ve got a month to make them come around. You want a drink, doc?”

Delagard was already pouring. Lawler took the cup and drank it off quickly.

“It’s time to knock off the bullshit, Nid. Time to dump this fantasy of yours about making them come around.”

Delagard glanced upward. By the pallid flickering light his round face seemed heavier than it actually was, the shadows high-lighting rolls of flesh around his throat, turning his tanned, leathery-looking cheeks to sagging jowls. His eyes seemed small and beady and weary.

“You think?”

“No question of it. They really want to be rid of us. Nothing we could say or do will change that.”

“They tell you that, did they?”

“They didn’t need to. I’ve been on this island long enough to understand that they mean what they say. So have you.”

“Yes,” Delagard said thoughtfully. “I have.”

“It’s time to face reality. There’s not a chance in hell that we can talk them into taking back their decree. What do you think, Delagard? Is there? For Christ’s sake, is there? ”

“No. I don’t suppose there is.”

“Then when are you going to stop pretending there is? Do I have to remind you what they did on Shalikomo when they said to go and people didn’t go?”

“That was Shalikomo, long ago. This is Sorve, now.”

“And Gillies are Gillies. You want another Shalikomo here?”

“You know the answer to that, doc.”

“All right, then. You knew from the first that there wasn’t any hope of changing their minds. You were just going through the motions, weren’t you? For the sake of showing everybody how concerned you were about the mess that you had singlehandedly created for us.”

“You think I’ve been bullshitting you?”

“I do.”

“Well, it isn’t so. Do you understand what I feel like, having brought all this down on us? I feel like garbage, Lawler. What do you think I am, anyway? Just a heartless bloodsucking animal? You think I can just shrug and tell the town, Tough tittie, folks, I had a good thing going there for a while with those divers and then it just didn’t work out, so we have to move, sorry for the inconvenience, so long, see you around? Sorve is my home community, doc. I felt I had to show that I’d at least try to undo the damage I caused.”

“Okay. You tried. We both tried. And got nowhere, as we both expected all along. Now what are you going to do?”

“What do you want me to do?”

“I told you before. No more windy talk about kissing the Gillies” flippers and begging them to forgive. We have to begin figuring out how we’re going to get away from here and where we’re going to go. Start making plans for the evacuation, Delagard. It’s your baby. You caused all this. Now you have to fix it.”

“As a matter of fact,” Delagard said slowly, “I’ve already been working on doing just that. Tonight while you were parleying with the Gillies I sent word to the three ships of mine that are currently making ferry trips that they should turn around and get back here right away to serve as transport vessels for us.

“Transporting us where?”

“Here, have another drink.” Delagard filled Lawler’s glass again without waiting for a response. “Let me show you something.”

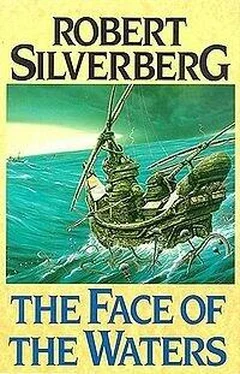

He opened a cabinet and took a sea-chart from it. The chart was a laminated plastic globe about sixty centimetres in diameter, made of dozens of individual strips of varying colours fitted together by some master craftsman’s hand. From within it came the ticking sound of a clockwork mechanism. Lawler leaned toward it. Sea-charts were rare and precious things. He had rarely had a chance to see one at such close range.

“Onyos Felk’s father Dismas made this, fifty years ago,” Delagard said. “My grandfather bought it from him when old Felk thought he wanted to go into the shipping trade and needed money for building ships. You remember the Felk fleet? Three ships. The Wave sank them all. Hell of a thing, pay for your ships by selling your sea-chart, then lose the ships. Especially when it’s the best chart ever made. Onyos would give his left ball to have it, but why should I sell? I let him consult it once in a while.”

Circular purple medallions the size of a thumbnail were moving slowly up and down along the chart, some thirty or forty of them, perhaps even more, driven by the mechanism within. Most went in a straight line, heading from one pole toward the other, but occasionally one would glide almost imperceptibly into an adjacent longitudinal strip, the way an actual island might wander a little to the east or to the west while riding the main current carrying it toward the pole. Lawler marvelled at the thing’s ingenuity.

Delagard said, “You know how to read one of these? These here are the islands. This is Home Sea. This island here is Sorve.”

A little purple blotch, making its slow way upward near the equator of the globe against the green background of the strip on which it was travelling: an insignificant speck, a bit of moving colour, nothing more. Very small to be so dear, Lawler thought.

“The whole world is shown here, at least as we understand it to be. These are the inhabited islands, in purple—inhabited by humans. This is the Black Sea, this is the Red Sea, this is the Yellow Sea over here.”

“What about the Azure Sea?” Lawler asked.

Delagard seemed a little surprised. “Way up over here, practically in the other hemisphere. What do you know about the Azure Sea, doc?”

“Nothing much. Someone mentioned it to me recently, that’s all.”

“A hell of a trip from here, the Azure Sea. I’ve never been there.” Delagard turned the globe to show Lawler the other side. “Here’s the Empty Sea. This big dark thing down here is the Face of the Waters. Do you remember the great stories old Jolly used to tell about the Face?”

“That grizzly old liar. You don’t actually believe he got anywhere near it, do you?”

Delagard winked. “It was a terrific story, wasn’t it?”

Lawler nodded and let his mind wander for a moment back close to thirty-five years, thinking of the weatherbeaten old man’s oft-repeated tale of his lonely crossing of the Empty Sea, of his mysterious and dreamlike encounter with the Face, an island so big you could fit all the other islands of the world into it, a vast and menacing thing filling the horizon, rising like a black wall out of the ocean in that remote and silent corner of the world. On the sea-chart, the Face was merely a dark motionless patch the size of the palm of a man’s hand, a ragged black blemish against the otherwise blank expanse of the far hemisphere, down low almost in the south polar region.

He turned the globe back to the other hemisphere and watched the islands slowly moving about.

Lawler wondered how a sea-chart made so long ago could predict the current positions of the islands in any useful way. Surely they were deflected from their primary courses by all sorts of short-term weather phenomena. Or had the maker of the chart taken that all into account, using some sort of scientific magic inherited from the great world of science in the galaxy beyond? Things were so primitive on Hydros that Lawler was always surprised when any kind of mechanism worked; but he knew that it was different on the other inhabited worlds of space, where there was land, and a ready supply of metals, and a way to move from world to world. The technological magics of Earth, of the old lost mother world, had carried over to those worlds. But there was nothing like that here.

Читать дальше