"That was the wrong conclusion to reach. The electron shows how quantum and classical properties can coexist. The fact that you can demonstrate some quantum behavior in a system doesn’t mean you’ve uncovered all that there is to be found.

"I believe that the Sarumpaet rules are classical rules . Part of the total state vector of any system obeys them, but not the whole. The part that does follow the Sarumpaet rules interacts with the environment one way: transforming its surroundings into what we think of as our own vacuum. But there are other parts that interact differently, creating other states. Because we can’t begin to track what’s really happening to the environment on the Planck scale, what we see is a single, certain, classical outcome: the Sarumpaet rules hold absolutely true, and our vacuum is absolutely stable."

A member of the audience stood, and Sophus acknowledged the request. "Tarek?"

"You’re claiming that the vacuum has been stabilized by something like the quantum Zeno effect?"

Tchicaya craned his neck to observe the questioner more closely. Tarek was the Preservationist who’d been trying to scribe Planck worms to devour the novo-vacuum, without waiting to discover what it was, or what it might contain. There was nothing fanatical about his demeanor, though; he merely radiated an impatience that everyone in the audience shared.

"It’s similar to that," Sophus agreed. "The quantum Zeno effect stabilizes systems through constant measurement. I believe that part of the total graph in which everything’s embedded measures the part we see as the vacuum, which also determines the dynamic laws that govern matter moving through that vacuum. It’s like the vapor in a cloud chamber, condensing in droplets around the path of a subatomic particle. The particle only appears to follow a definite trajectory because each path is correlated with a particular pattern of droplets — and the droplets have too many hidden degrees of freedom to exhibit quantum effects themselves. But we know there are branches where the particle follows different paths, surrounded by different trails of droplets."

Tarek frowned. "So why can’t we discover the path, the rules, that are holding sway behind the border?"

Sophus said, "Because what lies behind the border is not another vacuum, another set of rules. It has no classical properties like that to discover. It’s not that it couldn’t be divided up — formally, mathematically — into a sum of components, each obeying a different analog of the Sarumpaet rules. But we’re not correlated with any particular component, the way we are with our own vacuum, so we can’t expect to uncover any particular set of rules."

Tchicaya was exhilarated. It was too soon to take Sophus’s idea seriously, but there was something deeply appealing in the simplicity of the notion. Behind the border was a superposition of every possible dynamic law .

Tarek said, "We can’t measure those properties? Make them definite, if only for different branches of ourselves? When we interact with the novo-vacuum — or whatever you now wish to call it — shouldn’t we end up as a superposition of observers who each find definite laws?"

Sophus shook his head firmly. "Not by dropping a few Planckscale probe graphs into a system six hundred light-years wide. If there were preexisting laws behind the border, we might hope to discover them that way, but that’s not what we’re dealing with. On our side of the border, there’s a tight correlation stretching across all of space-time: the dynamics being followed at different times and places has become a tangle of mutual interdependence. What lies behind the border isn’t correlated from place to place, or from moment to moment. What we’re sampling with our probe graphs might as well be random noise at every level."

Rasmah stood, just ahead of a dozen other people. The others resumed their seats, and Tarek begrudgingly followed.

She said, "This is wonderful speculation, Sophus, but how do you plan to test it? Do you have any solid predictions?"

Sophus gestured at the space behind him, and a set of graphs appeared.

"As you see, I can match the borderlight spectrum. That’s not claiming much. I can match the half-c velocity of the border, which is slightly harder. And I can match the pooled results of all the experiments performed here so far: namely, their complete failure to identify anything resembling a dynamic law.

"So much for retrodiction. I’m making the following prediction: when we repeat the old experiments, re-scribe the old probe graphs, and monitor the results with your new spectrometer…we’ll find exactly the same thing, all over again. No patterns will emerge, no symmetries, no invariants, no laws.

"We’ve already discovered that there’s nothing to be discovered. All I can predict is that however hard we look, that absence will be confirmed."

Yann rolled off the bed and landed on the floor, laughing.

Tchicaya peered over the edge. "Are you all right?"

Yann nodded, covering his mouth with a hand but unable to silence himself.

Tchicaya didn’t know whether to be annoyed or concerned. Acorporeals taking on bodies often mapped them in unusual ways. Perhaps laughter was Yann’s only available response to some terrible psychic affront that Tchicaya had unwittingly inflicted.

"You’re sure I haven’t hurt you?"

Yann shook his head, still laughing helplessly.

Tchicaya sat on the edge of the bed, struggling to regain his own sense of humor. "This is not a reaction I’m accustomed to. Rejection and hilarity are perfectly acceptable responses, but they’re supposed to occur much earlier in proceedings."

Yann managed to regain some composure. "I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to offend you."

"I take it you’re not interested in finishing what you started?"

"Umm." Yann grimaced. "I could try, if it’s important to you. But I think it would be very difficult to take seriously."

Tchicaya planted a foot on his chest. "Next time you want an authentic embodied experience…just simulate it." He still felt a pang of lust at the touch of skin on skin, but it was fading into a kind of exasperated affection.

He crouched down and kissed Yann on the mouth, meaning it as a gesture of finality. Yann smiled, puzzled. "That was nice."

"Forget it." Tchicaya stood and started dressing.

Yann lay on the floor, watching him. "I think I’m getting all the signals you talked about," he mused. "But they’re so crude, even now. And before, it was just a single message, repeating itself endlessly: Be happy, be happy, be happy! Do you think there’s something wrong with this body?"

"I doubt it." Tchicaya sat cross-legged on the floor beside him.

"You expected more?"

"I was already happy, so it was a bit redundant."

"How happy?"

"As happy as it’s possible to be, for no particular reason."

"I have no idea how to interpret that. What gets to count as a particular reason?"

Yann shrugged. "Something more than being told by my body: Be happy. Be happy…why?"

"Because you’re with someone you like. And you’re making them happy, too."

"Yes, but only if they accept the same reasoning. That’s circular."

Tchicaya groaned. "Now you’re being disingenuous. It’s a tradition, passed down from reproductive biology. Every tradition’s arbitrary. That doesn’t mean it’s empty."

"I know. But I still expected something more subtle."

"That takes time."

"What, hours?"

"Centuries."

Yann narrowed his eyes with suspicion.

Tchicaya laughed, but made a face protesting his honesty. "On Turaev, it takes six months of attraction before anything’s physically possible." Like most generic bodies, the Rindler 's were promiscuous: any two of them could develop compatible sexual organs, more or less at will. You could wire in your own chosen restraints while you inhabited them, but since leaving home, Tchicaya had never felt the need to delegate the task. "The waiting was nice, in its own way," he admitted. "You might think it was risking an awful anticlimax, but I think the buildup improved the sex itself almost as much as it raised expectations. Acting on the spur of the moment is more likely to be disappointing."

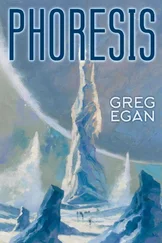

Читать дальше

![Грег Иган - Рассказы [компиляция]](/books/419837/greg-igan-rasskazy-kompilyaciya-thumb.webp)