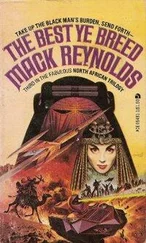

Homer shot a quick, impatient look at her. “The good doctor and his people are in the Sahara to work with the Tuareg and the Teda and the rest of the bedouin. Beyond that, he has the same dream we have—of developing this continent of our racial background.”

“But he doesn’t believe in your methods, Homer, and we’re forcing him to follow El Hassan’s road in spite of his beliefs.”

Moroka had been peering at the two of them narrowly. “You don’t make omelets without breaking eggs,” he said, his voice on the overbearing side.

She spun on him. “But the omelets don’t turn out so well if some of the eggs you use are rotten.”

The South African’s voice turned gentle. “Miss Cunningham,” he said, “working in the field, like this, can have its rugged side for a young and delicate woman …”

“Delicate!” she snapped. “I’ll have you know . …”

“Hey, everybody, hold it,” Cliff injected. “What goes on?”

Dave Moroka shrugged. “It just seems to me that Isobel might do better back in Dakar, or in New York with your friend Jake Armstrong. Somewhere where her sensibilities wouldn’t be so bruised, and where her assets”—his eyes went up and down her lithe body—“could be put to better use.”

Isobel’s sepia face had gone a shade or more lighter. She said, very flatly, “My assets, Mr. Moroka, are in my head.”

Homer Crawford said disgustedly, “O.K., O.K., let’s all knock it off.”

His eyes flicked back and forth between them, in definite command. “I don’t want to hear any more in the way of personalities between you two.”

Moroka shrugged again. “Yes sir,” he said without inflection.

Isobel turned away and took up some paperwork without further words. She suppressed her feeling of seething indignation.

Homer Crawford, under his pressures, was changing. Possibly, she had told herself before, it was change for the better. The need was for a strong man, perhaps even a ruthless one.

The Homer Crawford she had first known was an easier-going man than he who had snapped an abrupt order to her a moment ago. The Homer she had first known requested things of his teammates and friends. El Hassan had learned to command.

The Homer she had first known could never have ridden roughshod over the basically gentle Dr. Smythe.

The Homer she had first known, when the El Hassan scheme was still aborning, had thought of himself as a member of a team. He was quick to ask advice of all, and quick to take it if it had validity. Now Homer, as El Hassan, was depending less and less upon the opinions of those surrounding him and more and more upon his own decisions, which he seemed sometimes to reach purely through intuition.

The El Hassan dream was still upon her but, womanlike, she wondered if she liked the would-be tyrant of all North Africa as well as she had once liked the easygoing American idealist, Homer Crawford.

Jack and Jimmy Peters, the brothers from Trinidad, entered, the former carrying a couple of books.

They’d evidently failed to note the raised voices and wore their customary serious expressions. Jack looked at Homer and said, “ Ĉu vi scias Esperanton?”

Homer Crawford’s eyebrows went up but he said, “ Jes, mi parolas Esperanto tre bona, mi pensas.”

“ Bona” Jack said, “ Tre bona .”

“ Jes, estas bele ,” his brother said.

Moroka was scowling back and forth from one of them to the other. “I thought I had a fairly good working knowledge of the world’s more common languages,” he said, “but that goes by me. It sounds like a cross between Italian and pig-Latin.”

Homer said to the Peters brothers, “Let’s drop Esperanto so that Dave, Isobel and Cliff can follow us. We can give it a whirl later, if you’d like, just for the practice.”

Isobel said slowly, “ Mi parolas Esperanto, malgranda.” Then in English, “I took it for kicks while I was still in school. Kind of rusty now, though.”

“Esperanto?” Cliff said. “You mean that gobbledygook so-called international language?”

Jack Peters looked at him, serious-faced as always. “What is wrong with an international language, Mr. Jackson?”

Cliff was taken aback. “Search me. But it doesn’t seem to have proved very practical. It didn’t catch on.”

“Well, more than you might think,” Isobel told him. “There are probably hundreds of thousands of persons in one part of the world or another who can get along in Esperanto.”

Moroka said impatiently, “What’re a few hundred thousands of people in a world population like ours? Cliff’s right. It never took hold.”

Homer said, “All right, Jack and Jimmy. You boys evidently have something on your minds. Let everybody sit down and listen to it.”

Even before they got thoroughly settled, Jack Peters was launching into his pitch.

“We need an official language,” he said. “The El Hassan movement has set as a goal the uniting of all North Africa. We might start here in the Sahara, but it’s just a start. Ultimately, the idea is to reach from Morocco to Egypt and from the Mediterranean to … to where? The Congo?”

“Actually, we’ve never set exact limits,” Homer said.

“Ultimately all Africa,” Dave Moroka muttered softly. He ignored the manner in which Isobel contemplated him from the side of her eyes.

“All right,” the West Indian said, “There are more than seven hundred major languages, not counting dialects, in Africa. Sooner or later, we need an official language. What is it going to be?”

“Why one official language? Why not several?” Cliff scowled. “Say Arabic, here in this area. Swahili on the East coast. And, say, Songhoi along the Niger, and Wolof, the Senegalese lingua franca, and …”

“You see,” Peters interrupted. “Already you have half a dozen and you haven’t even got out of this immediate vicinity as yet. Let me develop my point.”

Homer Crawford was becoming interested. “Go on, Jack,” he said.

Jack Peters pointed a finger at him. “To be the hero symbol we have in mind, El Hassan is going to have to be able to communicate with all of his people. He’s not going to be able to speak Arabic to, say, a Masai in Kenya. They hate the Arabs. He’s not going to be able to speak Swahili to a Moroccan, they’ve never heard of the language. He can’t speak Tamaheq to the Imraguen, they’re scared to death of the Tuareg.”

Homer said thoughtfully, “A common language would be fine. It’d solve a lot of problems. But it doesn’t seem to be in the cards. Why not adopt as our official language the one in which the most of our people will be able to communicate? Say, Arabic?”

Jack was shaking his head seriously. “And antagonize all the Arab-hating Bantu in Africa? It’s no go, Homer.”

“Well, then, say French—or English.”

“English is the most international language in the world,” Moroka said. But his face was thoughtful, as those of the others were becoming.

The West Indian was beginning to make his points now. “No, any of the European languages are out. The white man has been repudiated. Adopting English, French, Spanish, Portuguese or Dutch as our official language would antagonize whole sections of the continent.”

“Why Esperanto?” Cliff scowled. “Why not, say, Nov-Esperanto, or Ido, or Interlingua?”

Jimmy Peters put in a word now. “Actually, any one of them would possibly do, but we have a head start with Esperanto. Some years ago both Jack and I became avid Esperantists, being naive enough in those days to think an international language would ultimately solve all man’s problems. And both Homer and Isobel seem to have a working knowledge of the language.”

Читать дальше