“I’ll do nothing for you. You can leave now.”

Martha reached for the doorknob as he took her by the upper arm, his fingers sinking in like steel hooks. She gasped with pain as he dragged her away from it, pulling her up close to him, speaking into her face from inches away. His breath smells of Sen-Sen, she thought. I didn’t know they still made it.

She was ready to cry, her arm hurt so much.

“Listen you, you are going to do like I say. If you want a reason other than loyalty to your country—just remember that I have a roll of film from your camera with your fingerprints all over it, and pictures of your floor. The Danes would love to see that, wouldn’t they?”

His smile made her think of a rictus, the kind that was supposed to be on people’s faces when they died of pain. She disengaged her arm from his grasp and stepped back. It would be a complete waste to tell this man what she thought of him.

“What do you want me to do?” she asked finally, looking at the floor as she said it.

“That’s more like it. You’re a great camera addict, so take this brooch. Pin it onto your purse before you go.”

She held it in her palm; it was not unattractive and would go well with her black alligator. A large central stone was surrounded by a circle of diamond chips and what could be small rubies. It was finished in hand-chased gold, rimmed by ornate whorls.

“Point your purse and press here?,” he said, indicating the top whorl. “It’s wide angle, the opening is preset, it will work in almost any light. There are over a hundred shots in here so be generous. I want pictures of the bridge and the engine room if you get there, close-ups of the controls, shots of hallways, stairs, doors, compartments, airlocks. Everything. Later on I will show you prints and you will be asked to describe what they are, so take close notice of everything and the sequence of your visit through the ship.”

“I don’t know anything about this kind of work. Can’t you get someone else, please? There will be hundreds there… ”

“If we had anyone else—do you think we would be asking you !” The last word was spoken with cold contempt, thrown at her as he bent to pick up the brushes. He shook a dishmop in her direction.

“And don’t go making little accidents like dropping it, or breaking it, or exposing all the film in the dark and blaming us. I know all the tricks. You have no choice. You will take the pictures as I have told you. Here, this is for you.” He handed her a brush, smiling coldly, sure of himself. He opened the door and was gone.

Martha looked down at it—then hurled it from her. Yes, that’s what he thought. A toilet brush. She was shaking as she went to finish dressing.

* * *

“Look at the crowds!” Ove said, steering around a busload of cheering students who were waving flags from all the windows.

“Can you blame them?” Ulla asked. She was sitting in the back of the car with Martha. “This is certainly a wonderful day.”

“Weather too,” Ove said, glancing up at the sky. “Plenty of clouds, but no rain. No sun—but you can’t have everything.”

Martha sat silently, clutching her purse, the big gold brooch prominent on the flap. Ulla had noticed it, and she had had to make up a quick lie.

It would have been impossible to get close to the waterfront if they had not had their official invitation. They were waved through the barriers, and directed to Amalien-borg Palace, where the immense square had been sec-tioned off for parking. From there it was a short walk down Larsens Piads to the water’s edge. There was a holiday air even here, with a band playing lustily, bunting flapping on the stands erected on the dock, the guests nodding to each other as they took their places.

“Ten minutes,” Ove said looking at his watch. “We had better hurry. Unless Martha thinks her husband will be late?”

“Nils!”

They all laughed at the thought, Martha along with the others. For seconds at a time she would feel right at home here, being ushered to her seat—not ten feet from the King and the Royal Family—smiling happily at friends. Then memory would return with a sinking in her midriff, and she would clutch at her purse, sure that people were looking at it. Then the band broke into “King Christian,” the Royal Anthem, and there was a great rustling as everyone rose. After that the National Anthem, “There Is a Lovely Land,” terminating with a great flourish on the drums. The last notes died away and they sat down, and at almbst the same instant a distant whistling sound could be heard. They all looked up, shielding their eyes, trying to see. The sound deepened, turned to a rumble, and a dark speck broke through the layer of clouds high above.

“Right on time, to the second!” Ove said, excited.

With startling suddenness the dot grew, enlarged to giant proportions, appearing to fall straight toward them. There were gasps from the audience, and a choked-off scream.

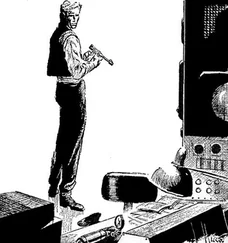

The speed slowed, more and more, until the great shape was drifting down as softly as a falling feather, dropping toward the still water of the Inderhavn before them. There were more gasps as its true size became obvious. The great white and black hull was as big as any ocean-going ship, thousands of tons of dead weight. Falling. There was something unbelievable about its presence in the air before them. An immense disk, a half a city block long, flat on top and bottom, with the windowed bulge of the bridge protruding from the leading edge. It had no obvious means of propulsion; there was no sound other than the air rushing around its flanks.

Absolute silence gripped the onlookers, so hushed that the cries of the seagulls could be clearly heard. The great ship came to a complete halt, airborne, a few meters above the water. Then, with infinite precision, it dropped lower. Easing its tremendous bulk into the water so carefully that only a single small wave eased out to slap against the face of the wharf. As it moved closer, hatches opened on its upper decks and men brought out lines to secure it.

A spontaneous cheer broke out as the onlookers surged to their feet, shouting at the top of their lungs, clapping, the enthusiastic music of the band drowned out by their joyous noise. Martha shouted along with the others, everything else forgotten in the wild happiness of the moment.

In strong black letters, picked out against the white, the ship’s name could be clearly read. Holger Danske. The proudest name in Denmark.

Even before the lines were secured, a passenger ramp was pushed out to the opened entrance. A small knot of officials was waiting to welcome the officers who strode down to them. Even at this distance Nils’s great form was clearly visible among the others. They saluted, shook hands, and cajne forward to the reviewing stand. Nils passed close enough to smile when Martha waved.

After that there were honors and awards, a few brief words from the King, some longer speeches from the politicians. It was the Prime Minister who made the official pronouncement. He stood for a long moment, the wind whipping free strands of his hair, looking at the great ship before him. When he spoke, there was a heartfelt sincerity in his words.

uIn the old legend, Holger Danske lies sleeping, ready to wake and come to Denmark’s aid when she is in need. During the war the resistance movement took the name Holger Danske, and it was used with honor. Now we have a vessel by that name, the first of many, that will aid Denmark in a way no one ever suspected.

“We are opening up the solar system to mankind. This accomplishment is so grand that it is almost beyond imagining. I like to think about the seas of space as another ocean to be crossed the way Danish seafarers crossed in the nineteenth century, with new and fantastic lands on the other side. Science shall profit, from the observatory and the cryogenic laboratories now being built on the Moon. Industry shall profit, from the new sources of raw materials waiting for us out there. Mankind shall profit, because this is a joint venture of all the nations of the world. It is our fondest hope that the cause of peace shall profit—because out there, in space, our world is small and veiled and far away. Looking from there it is hard to see the separate continents, while national boundaries are completely invisible. Vital evidence that we are one world, one mankind.

Читать дальше