But even while working on deadly machines for the future, Benjamin couldn’t stop dreaming about the past, any more than Edgar Evans had.

Then, after eighteen years, Benjamin was fired. The military had asked for a new study on the question of how many enemy missiles might get through the early warning and intercept rings and reach the cities. "What, specifically, can we do to protect our people?"

When the study was finished, a huge brassbound conference was staged at the lab and everybody was expectant.

"We have a single recommendation," said Benjamin calmly, and they were quiet, for Benjamin and his group were the big brains. "At the earliest warning, tell everybody to run like hell!"

So the lab fired him, though the public statement read that he was "resigning to pursue independent research."

Benjamin was shocked at first, and hurt, but dinner and party invitations came as often as ever from his old associates, and their wives went right on with that ancient game of trying to find the "right" girl for the bachelor friend. He would never mention it, of course, but the girls nowadays seemed too direct and aggressive for him. They lacked that womanly modesty or engaging demureness that girls reportedly had once possessed. He wished—

* * *

Offers came in from other companies, but Benjamin had money enough for a while and he began experimenting with some ideas. When his lawyer and banker discovered he’d given away two new color TV circuits, however, there was a blow-up and Benjamin found himself incorporated.

It made no difference. He could still experiment as he pleased. He had his many friends and constantly made more. If enough money rolled in to make him moderately wealthy, let the lawyer worry about it. After he came up with the Ben Reeves capacitor in 1961, his wealth was more than moderate. That thumb-sized gadget delivered the power of a hundred storage batteries and was the answer to a thousand engineering problems.

All down the bad years, Benjamin had read the papers and wondered and suffered through the tensions of the nerve war like the rest of us. Perhaps it was a little worse for him, because he knew the classified secrets, knew to the decimal point the percentage of missiles that would get through our defenses. Steadily the urge grew stronger to get out of this world gone suicidally awry.

He had the money and he had the time. An efficient business manager took care of the new plant that produced the Ben Reeves capacitor.

He built his first machine in 1962, a month before Andover Hare took his own near relatives back into time with him. But that wasn’t enough for Benjamin. He was a scientist where Andover was a student and Edgar Evans an amateur experimenter. Benjamin couldn’t forget the millions who yearned with him.

For Benjamin, the mere machine wasn’t an answer. He went back through the years himself, several times, but always he returned and worked harder. And there came the day, a year ago, when his work shifted suddenly to maps and population indices.

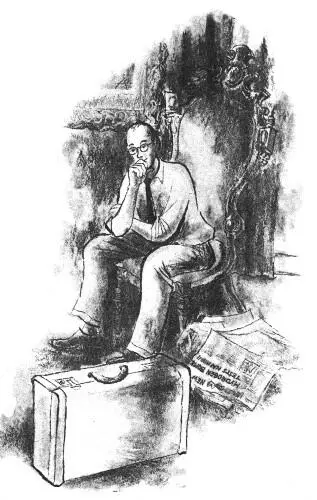

If you live within 40 miles of the most populous cities, you should know that somewhere in that city is a very plain suitcase which is at once an answer to your prayers and to those strange nostalgic desires you’ve felt. It may be in a rented room or a storage warehouse, or in the attic of one of the many friends Benjamin Reeves has made.

Wherever it is, you’re under its influence, thanks to Benjamin’s work. And every other day now, in a closed-off room at the Ben Reeves plant, technicians finish assembling another group of strange circuits which goes into another plain suitcase to be sent to yet another city, chosen on the basis of population vs. importance as a target.

The technicians are learning speed. Be thankful for that, if you love your fellow-man as Benjamin does. At first they turned out only one machine a week; soon it will be one a day, then two, four.

* * *

* * *

Benjamin doesn’t go out any more. He’s always within hearing of the receiver tuned to the warning networks, within reach of the red button that will someday send out a coded signal.

* * *

Did you read about the situation in this morning’s papers? It looks like another crisis in the making and maybe this time neither side will back down.

Pray for a year’s time, if you’re the praying kind.

But whenever the missiles come, Benjamin will press the red button at the first warning. The temporal field lasts only a millisecond and the missiles won’t be stopped, of course—but every city with a suitcase will be empty when they strike.

If the crisis holds off for a year, Benjamin figures we’ll all go back together, each city and town to a different time, but all before 1900. It’s hard to wait even a year when you have the gene gnawing and nagging inside you….

Edgar Evans, who started it, couldn’t wait. Andover Hare refused to go back alone. Benjamin Reeves, with the same gene, was unable to forget what he told the military—run like hell!—and all the folks like us who couldn’t.

So Benjamin found us the ultimate way to run, and to satisfy our dream in the running. Not yet, but soon now.

See you back there!