“When were you a student here?”

“In the ’70s. I haven’t been back very often.”

“Have things changed much?”

Peterson smiled reminiscently. “I dare say my rooms haven’t changed much. Picturesque view of the river and all my clothes get moldy from the damp…” He shook off his mood. “I’ll have to be getting back to London soon.”

They elbowed through the students to the door and out into the street. The June sunshine was dazzling after the pub’s dark interior. They stood for a moment, blinking, on the narrow sidewalk. Pedestrians stepped off into the street to walk past them and cyclists swerved around the pedestrians with a trilling of bells. They turned left and strolled back towards King’s Parade. On the corner opposite the church, they paused to look in the windows of Bowes & Bowes bookstore.

“Do you mind if I go in for a minute?” Peterson asked. “There’s something I want to look for.”

“Sure. I’ll come in, too. I’m a bookstore freak; never pass one by.”

Bowes & Bowes was almost as crowded as the Whim had been earlier, but the voices here were subdued. They edged cautiously between the knots of students in black gowns and pyramids of book’s on display. Peterson pointed out one on a less conspicuous table towards the back of the store.

“Have you seen this?” he asked, picking up a copy and handing it to Markham.

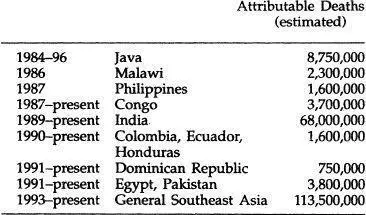

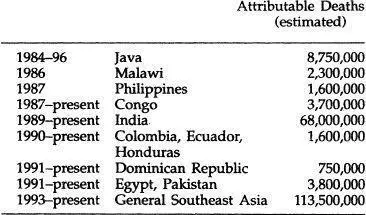

“Holdren’s book? No, I haven’t read it yet, though I talked to him about it. Is it good?” Markham looked at the title, stamped in red on a black cover— The Geography of Calamity: Geopolitics of Human Dieback by John Holdren. In the bottom right corner was a small reproduction of a medieval engraving of a grinning skeleton with a scythe. He thumbed through it, paused, began to read. “Look at this,” he said, holding the book out to Peterson. Peterson ran his eyes over the chart and nodded.

Markham whistled softly. “Is it accurate?”

“Oh, yes. Underestimated, if anything.”

Peterson moved towards the back of the store. A girl was perched on a high stool adding a column of figures into an auto-accountant. Her fair hair hung forward, hiding her face. Peterson studied her covertly while leafing through some of the books in front of him. Nice legs. Fashionably dressed in some frilly peasant style he disliked. A blue Liberty scarf artfully arranged at her neck. Slim now, but not for many more years, probably. She looked about nineteen. As though aware of his gaze, she looked up straight at him. He continued to stare at her. Yes, nineteen and very pretty and very aware of it, too. She slid from her stool and, clutching papers defensively to her chest, came over to him.

“May I help you?”

“I don’t know,” he said with a slight smile. “Maybe. I’ll let you know if you can.”

She took this as a flirtatious overture and responded with a routine which probably, he reflected, was a knock-out with the local boys. She turned away from him and looked back over her shoulder, saying huskily, “Let me know then.” She gave him a long look from under her lashes, then grinned cheekily and flaunted her ways towards the front of the store. He was amused. At first, he had really thought that she intended her coquettish routine seriously, which would have been ludicrous if she hadn’t been so pretty Her grin showed that she was playacting. Peterson felt suddenly in very good spirits and almost immediately noticed the book he had been looking for.

He picked it up and went to look for Markham. The girl was with two others, her back to him. Her companions were laughing and staring. They obviously told her he was watching them, because she turned to look at him. She really was exceptionally pretty. He made a sudden decision. Markham was browsing through the science fiction selection.

“I have a couple of errands,” Peterson said. “Why don’t you go on ahead and tell Renfrew I’ll be there in half an hour?”

“Okay, fine,” Markham said. Peterson watched him as he strode out the door, moving athletically, and disappeared into the alley behind the building known as Schools.

Peterson looked for the girl again. She was serving someone else, a student. He watched as she went through another routine, leaning forward more than was necessary to write a receipt, quite enough to enable the student to look down the front of her blouse. Then she straightened up and looked quite offhand as she gave him his book in a white paper bag. The student went out, with a disconcerted look on his face. Peterson caught her eye and lifted the book in his hand. She slammed the cash register shut and came over to him.

“Yes?” she asked. “Have you made up your mind?”

“I think so. I’ll take this book. And maybe you could help me with something else. You live in Cambridge, do you?”

“Yes. You don’t?”

“No, I’m from London. I’m on the Council.” He despised himself immediately. Like shooting a rabbit with a cannon. No artistry at all. Anyway, he had all her attention now, so he might as well take advantage of it. “I wondered if you could recommend any good restaurants around here to me?”

“Well, there’s the Blue Boar. And there’s a French one in Grantchester that’s supposed to be good, Le Marquis. And a new Italian one, II Pavone.”

“Have you eaten at any of them?”

“Well, no…” She blushed slightly and he knew she regretted appearing at a disadvantage. He was well aware that she had named the three most expensive restaurants. His own favorite had not been mentioned; it was less showy and less expensive, but the food was excellent.

“If you could choose, which one would you go to?”

“Oh, Le Marquis. It looks a lovely place.”

“The next time I’m up from London, if you’re not doing anything, I would count it as a great favor if you would have dinner there with me.” He smiled intimately at her. “It gets pretty dull, traveling alone, eating alone.”

“Really?” she gasped. “Oh, I mean…” She struggled furiously to repress her triumphant excitement. “Yes, I’d like that very much.”

“Fine. If I could have your telephone number…”

She hesitated and Peterson guessed she had no telephone. “Or if you’d rather, I can simply stop by this shop early on.”

“Oh yes, that would be best,” she said, seizing on this graceful out.

“I’ll look forward to it.”

They walked forward to the front desk, where he paid for his book. When he left Bowes & Bowes, he turned the corner towards Market Square. Through the side windows of the bookstore he could see her in consultation with her two friends. Well, that was easy, he thought. Good God, I don’t even know her name.

He crossed the square and walked through Petty Cury with its bustling throng of shoppers, coming out opposite Christ’s. Through its open gate the green lawn in its quad was visible and behind that, the vivid colors of a herbaceous border against the gray wall of the Master’s Lodge. In the gateway the porter sat reading a paper. A knot of students stood studying some lists on the bulletin board. Peterson kept on going and turned into Hobson’s Alley. He finally found the place he was looking for: Foster and Jagg, coal merchants.

CHAPTER TEN

JOHN RENFREW SPENT SATURDAY MORNING PUTTING up new shelving on the long wall in their kitchen. Marjorie had been after him for months to do it. Her bland asides about where the planes of wood should go “when you get around to it” had slowly accreted into a pressing weight, an agreed duty, unavoidable. The markets were open only a few days each week—“to avoid fluctuations in supply” was the common explanation, rendered on the nightly news—and with the power cuts, refrigerating was impossible. Marjorie had turned to putting up vegetables and was amassing a throng of thick-lipped jars. They waited in cardboard boxes for the promised shelving.

Читать дальше