“But the writing—it is so wooden. The characters have no life. The plot makes me sleepy.”

“By the Blue Light of Seraph, Cor! It’s ideas that make this great. ‘Pride of Iron’ is based on spectro results that aren’t even in print yet.”

“Phooey. There have been stories with this theme before: Ti Liso’s Hidden Empire series. He had houses made of iron, streets paved with copper.”

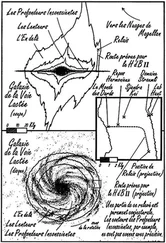

“Anyone who owns jewelry could imagine a world like that. This is different. Alecque is a chemist; he uses metals in realistic ways—like in gun barrels and heavy machinery. But even that isn’t the beauty of this story. Three hundred years ago, Ti Liso was writing fantasy; Ivam Alecque is talking about something that could really be. ” Rey covered the glowpots and threw open a window. Cold air oozed into the office, ocean breeze further cooled by the eclipse. The stars spread in their thousands across the sky, blocked only by the Barge’s rigging, dimmed only by mists rising from the pulper rooms below decks. Even if they had been standing outside, and could look straight up, Seraph would have been nothing more than a dim reddish ring. For the next hour, the stars ruled. “Look at that, Cor. Thousands of stars, millions beyond those we can see. They’re suns like ours, and—”

“—and we buy plenty of stories with that premise.”

“Not like this one. Ivam Alecque knows astronomers at Krirsarque who are hanging spectro gear on telescopes. They’ve drawn line spectra for lots of stars. The ones with color and absolute magnitude similar to our sun show incredibly intense lines for iron and copper and the other metals. This is the first time in history anyone has had direct insight about how things must be on planets of other stars. Houses built of iron are actually possible there.”

Ascuasenya was silent for a moment. The idea was neat; in fact, it was kind of scary. Finally she said, “We’re all alone in being so ‘metal poor?’ ”

“Yes! At least among the sun-like stars these guys have looked at.” “Hmm. … It’s almost like the gods, they play a big joke on us.” Cor’s great love was polytheistic fantasy, stories where the fate of mortals was determined by the whim of supernatural beings. That sort of thing had been popular in Fantasies early centuries. She knew Rey considered it out of step with what the magazine should be doing now. Sometimes she brought it up just to bug him. “Okay. I see why you want the story. Too bad it’s such an ugly little thing.”

She saw that her point had struck home. A bit grumpily, Rey unmasked the lamps, then sat down and picked up “Pride of Iron.” It really was plotless. And—on this leg of the voyage, anyway—he was the only one capable of pumping it up. … She could almost see the wheels going around in his head: But it would be worth rewriting! He could have the story published before these ideas were even in the scientific literature. He looked up, grinned belligerently at her, and said, “Well, I’m going to buy it, Cor. Assume ‘anonymous collaboration’ makes it twice as long: what can we do for illustrations?”

It took about fifteen minutes to decide which crew-artists would work the job; the Osterlai issue would use slightly modified stock illos. Hopefully, they could commission some truly striking pictures as they passed through that island chain.

The rest of the Osterlai issue was easy to lay out; several of the stories were already in the Osterlai language. The issue would be mostly fantasy, the new artwork would be from artists of Crownesse and the Chainpearls. The cover story was a rather nice Hrala adventure.

“Speaking of Hrala,” said Rey, “how is your project coming? Will your girl be able to give a show when we start peddling this issue?”

“Sure she will. We get about an hour of rehearsal every wake period. Once she understands about stage performance, things will go just fine. So far, we work on sword and shield stuff. She can memorize things as fast as we can show her. She’s awful impressive, screaming around the stage with Death in her hand.” In the stories, the Hrala Sword was magical, metal, and so heavy that an ordinary warrior could not lift it. The Tarulle version of Death was made of wood painted silver.

“What about her costume?” Or lack of one.

“Great. We still gotta do changes—ribbon armor is hard to fit—but she looks tremendous. Svektr Ramsey thinks so too.”

“He saw her?” Guille looked stricken.

“Don’t worry, Boss. The overeditor was amused. He told me to congratulate you for hiring her.”

“Oh. … Well, let’s hope we’re all still amused when you put her on stage with other actors.”

Cor gathered up the manuscripts they had chosen. She would take them, together with the production notes, over to the art deck. “No problem. You were right, she understands some Spräk. She can even speak it a little. I think she was just shy that first day. Onstage she’ll mainly scream gibberish—we won’t need a new script for each archipelagate.” Cor carried the papers to the door. “Besides, we get the chance to put it all together before we reach the Osterlais. We arrive at the Village of the Termite People in three days; I’ll have things ready by then.”

Guille chuckled. The Termite People were scarcely your typical fans. “Okay, I look forward to it.”

Cor stepped into the darkness, shut the hatch behind her. In fact, she was at least half as confident as she sounded. Things ought to work out, if she could just find time to coach Tatja Grimm. The giant little girl was stranger than Cor had admitted. She wasn’t really dumb, just totally deprived. She’d been born in some very primitive tribe. She’d been five years old before she ever saw a tree. Everything she saw now was a novelty. Cor remembered how the girl’s eyes had widened when Cor showed her a copy of Fantasie, and explained how spoken words could be saved with paper and ink. She had held the magazine upside down, paged back and forth through it, fascinated by both pictures and text.

Worst of all, Tatja Grimm had no concept of polemic; she must have been an outsider even in her own tribe. She simply did not accept that dramatic skits could persuade. If Grimm could be convinced of that single point, Cor was sure the Hrala campaign would be a spectacular success. If not, they might all end up with bat dreck on their faces.

The day they were to land at the Village of the Termite People, Rey took the morning off. He walked around the top editorial deck, looking for a place sheltered from the wind and passersby. This would be his first chance to play with his telescope since Fair Haven.

The marvelous weather still held. The sky was washed clean; widely spaced cumulus spread away forever. A Tarulle hydrofoil loitered about a mile ahead of the barge, its planes raised and sails mostly reefed. Guille knew there were others out there; most of the barge’s ’foil bays were empty. The fastboats had many uses. In civilized seas, they ranged ahead of and behind the barge—making landfall arrangements, carrying job orders, picking up finished illustrations and manuscripts. In the wilderness east of Fair Haven, they had a different role: security. No pirates were going to sneak up on the barge. The catapults and petroleum bombs would be ready long before any hostile vessel broke the horizon.

So far, all the traffic was friendly. Several times a day they met ships and barges coming from the east. Most were merchantmen. Only a few publishing companies had Tarulle’s worldwide scope. The hydrofoils reported that the Science was docked at the Village of the Termite People. That ship was much smaller than the Tarulle Barge, but it published its own journal. It was sponsored by universities in the Tsanarts as a sort of mobile research station.

Читать дальше