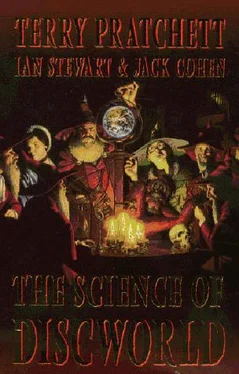

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld I» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld I

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld I: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld I»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld I — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld I», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We first began to realize this when we found evidence of the most recent snowball. About one and a half million years ago, round about the time that humans began to become the dominant species on Earth, the planet got very cold. The old name for this period was the Ice Age. We don't call it that any more because it wasn't one Age: we talk of 'glacial-interglacial cycles'. Is there a connection? Did the cold climate drive the naked ape to evolve enough intelligence to kill other animals and use their fur to keep warm? To discover and use fire?

This used to be a popular theory. It's possible. Probably not, though: there are too many holes in the logic. But a much earlier, and much more severe, Ice Age very nearly put a stop to the whole of that 'life' nonsense. And, ironically, its failure to do so may have unleashed the full diversity of life as we now know it.

Thanks to the pioneering insights of Louis Agassiz, Victorian scientists knew that the Earth had once been a lot colder than it is now, because they could see the evidence all around them, in the form of the shapes of valleys. In many parts of the world today you can find glaciers, huge 'rivers' of ice, which flow, very slowly, under the pressure of new ice forming further uphill. Glaciers carry large quantities of rock, and they gouge and grind their way along, forming valleys whose cross-section is shaped like a smooth U. All over Europe, indeed over much of the world, there are identical valleys, but no sign of ice for hundreds or thousands of miles. The Victorian geologists pieced together a picture that was a bit worrying in some ways, but reassuring overall. About 1.6 million years back, at the start of the Pleistocene era, the Earth suddenly became colder. The ice caps at the poles advanced, thanks to a rapid buildup of snow, and gouged out those U-shaped valleys. Then the ice retreated again. Four times in all, it was thought, the ice had advanced and retreated, with much of Europe being buried under a layer of ice several miles thick.

Still, there was no need to worry, the geologists said. We seemed to be safe and snug in the middle of a warm period, with no prospect of being buried under miles of ice for quite some time ...

The picture is no longer so comfortable. Indeed, some people think that the greatest threat to humanity is not global warming, but an incipient ice age. How ironic, and how undeserved, if our pollution of the planet cancels out a natural disaster!

As usual, the main reason we now know a lot more is that new kinds of observation became possible, propped up by new theories to explain what it is that they measure and why we can be reasonably sure that they do. These new methods range from clever methods for dating old rocks to studies of the proportions of different isotopes in cores drilled from ancient ice, backed up by ocean-drilling to study the layers of sediment deposited on the sea floor. Warm seas sustain different living creatures, whose death deposits different sediment, so there is a link from sediments to climate.

All of these methods reinforce each other, and lead to very much the same picture. Every so often the Earth begins to cool, becoming 10°-15°C colder near the poles and 5°C colder elsewhere. Then it suddenly warms up, possibly becoming 5°C warmer than the current norm. In between big fluctuations, there are smaller ones: 'mini ice ages'. The typical gap between a decent-sized ice age and the next is around 75,000 years, often less, nothing like the comfortable 400,000 years of 'interglacial' expected by the Victorians. The most worrying finding of all is that periods of high temperatures, that is, like we get now, seldom lasted more than 20,000 years.

The last major glaciation ended 18,000 years ago.

Wrap up well, folks.

What caused the ice ages? It turns out that the Earth isn't quite as nice a planet as we like to think, and its orbit round the sun isn't quite as stable and repetitive as we usually assume. The currently accepted theory was devised in 1920 by a Serbian called Milutin Milankovitch. In broad terms, the Earth goes round the sun in an ellipse, almost a circle, but there are three features of the Earth's motion that change. One is the amount through which the Earth's axis tilts, about 23° at the moment, but varying slightly in a cycle that lasts roughly 41,000 years. Another is a change in the position of Earth's closest approach to the sun, which varies in a 20,000-year cycle. The third is a variation in the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit, how oval it is, whose period is around 100,000 years. Putting all three cycles together, it is possible to calculate the changes in heat received from the sun. These calculations agree with the known variations in the Earth's temperature, and it seems particularly likely that the Earth's warming up after ice ages is due to increased warmth from the sun, thanks to these three astronomical cycles.

It may seem unsurprising that when the Earth receives more heat from the sun, it warms up, and when it doesn't, it cools down, but not all of the heat that reaches the upper atmosphere gets down to the ground. It can be reflected by clouds, and even if it gets to ground level it can be reflected from the oceans and from snow and ice. It is thought that during ice ages, this reflection causes the Earth to lose more heat than it would otherwise do, so ice ages automatically make themselves morse. We get kicked out of them when the incoming heat from the sun is so great that the ice starts to melt despite the lost heat. Or maybe the ice gets dirty, or ... It's not so clear that we get kicked into an ice age when less of the sun's warmth reaches the Earth, indeed the slide into an ice age is usually more gradual than the climb back out of it.

All of which makes one wonder whether global warming caused by gases excreted from animals might be partly responsible. When gases such as carbon dioxide and methane build up in the atmosphere, they cause the famous 'greenhouse effect', trapping more sunlight than usual, hence more heat. Right now, most scientists have become convinced, the Earth's supply of 'greenhouse gases' is growing faster than it would otherwise do thanks to human activities such as farming (burning rainforests to clear land), driving cars, burning coal and oil for electricity, and farming again (cows produce a lot of methane: grass goes in one end and methane emerges at the other). And how could we forget the carbon dioxide breathed out by people? One person is equivalent to half a car, maybe more.

Maybe in the past there were vast civilizations of which we now know nothing, all traces having vanished, except for their effect on the global temperature. Maybe the Earth seethed with vast herds of cattle, buffalo, elephants busily excreting methane. But most scientists think that climate change results from variations in five different factors: the sun's output of radiant heat, the Earth's orbit, the composition of the atmosphere, the amount of dust produced by volcanoes, and levels of land and oceans resulting from movement of the Earth's crust. We can't yet put together a really coherent picture in which the measurements match the theory as closely as we'd like, but one thing that is becoming clear is that the Earth's climate has more than one 'equilibrium' state. It stays in or near one such state for a while, then switches comparatively rapidly to another, and so on.

The original idea was that one state was a warm climate, like the one we have now, and the other was a cold 'ice age' one. In 1998 Didier Paillard refined this idea to a three-state model: interglacial (warm), mild glacial (coldish), and glacial (very cold). A drop in heat received from the sun below some critical threshold, caused by those astronomical cycles, triggers a switch from warm to coldish. When the resulting ice builds up sufficiently, it reflects so much of the sun's heat that this triggers another switch from coldish to very cold. But when the sun's heat finally builds up again to another threshold value, thanks once more to the three astronomical cycles, then the climate switches back to warm. This model fits observations deduced from the amount of oxygen-18 (a radioactive isotope of oxygen) in geological deposits.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld I» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld I» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.