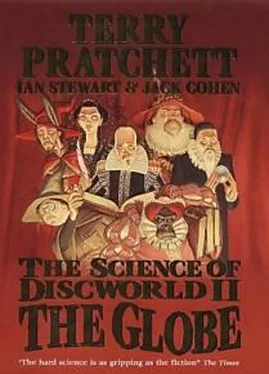

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld II - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld II - The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Ridcully suspected that Ponder Stibbons would invoke 'quantum' to explain anything really bizarre, like the disappearance of the Shell Midden People. The quantum world is bizarre, and this kind of invocation is always tempting. In an attempt to make sense of the quantum universe, several physicists have suggested founding all quantum phenomena (that is, everything) on the concept of information. John Archibald Wheeler coined the phrase 'It from Bit' to capture this idea. Briefly, every quantum object is characterised by a finite number of states. The spin of an electron, for instance, can either be up or down, a binary choice. The state of the universe is therefore a huge list of ups and downs and more sophisticated quantities of the same general kind: a very long binary message.

So far, this is a clever and (it turns out) useful way to formalise the mathematics of the quantum world. The next step is more controversial. All that really matters is that message, that list of bits.

And what is a message? Information. Conclusion: the real stuff of the universe is raw information. Everything else is made from it according to quantum principles. Ponder would approve.

Information thereby takes its place in a small pantheon of similar concepts -velocity, energy, momentum -that have made the transition from convenient mathematical fiction to reality.

Physicists like to convert their technically most useful mathematical concepts into real things: like Discworld, they reify the abstract. It does no physical harm to 'project' the mathematics back into the universe like this, but it may do philosophical harm if you take the result literally.

Thanks to a similar process, for example, entirely sane physicists today insist that our universe is merely one of trillions that coexist in a quantum superposition. In one of them you left your house this morning and were hit by a meteorite; in the one in which you're reading this book, that didn't happen. 'Oh, yes,' they urge: 'those other universes really do exist. We can do experiments to prove it.'

Not so.

Consistency with an experimental result is not a proof, not even a demonstration, that an explanation is valid. The 'many-worlds' concept, as it is called, is an interpretation of the experiments, within its own framework. But any experiment has many interpretations, not all of which can be 'how the universe really does it'. For example, all experiments can be interpreted as

'God made that happen', but those selfsame physicists would reject their experiment as a proof of the existence of God. In that they are correct: it's just one interpretation. But then, so are a trillion coexisting universes.

Quantum states do superpose. Quantum universes can also superpose. But separating them out into classical worlds in which real-life people do real-life things, and saying that those superpose, is nonsense. There isn't a quantum physicist anywhere in the world that can write down the quantum-mechanical description of a person. How, then, can they claim that their experiment

(usually done with a couple of electrons or photons) 'proves' that an alternate you was hit by a meteorite in another universe?

'Information' began its existence as a human construct, a concept that described certain processes in communication. This was 'bit from it', the abstraction of a metaphor from reality, rather than 'it from bit', the reconstruction of reality from the metaphor. The metaphor of information has since been extended far beyond its original bounds, often unwisely. Reifying information into the basic substance of the universe is probably even more unwise. Mathematically, it probably does no harm, but Reification Can Damage Your Philosophy.

19. LETTER FROM LANCRE

Granny Weatherwax, known to all and not least to herself as Discworld's most competent witch, was gathering wood in the forests of Lancre, high in the mountains and far from any university at all.

Wood gathering was a task fraught with danger for an old lady so attractive to narrativium. It was quite hard these days, when gathering firewood, to avoid third sons of kings, young swineherds seeking their destiny and others whose unfolding adventure demanded that they be kind to an old lady who would with a certainty turn out to be a witch, thus proving that smug virtue is its own reward.

There is only a limited number of times even a kindly disposed person wishes to be carried across a stream that they had, in fact, not particularly desired to cross. These days, she kept a pocket full of small stones and pine cones to discourage that kind of thing.

She heard the soft sound of hooves behind her and turned with a pine cone raised.

'I warn you, I'm fed up with you lads always on the ear'ole for three wishes—' she began.

Shawn Ogg, astride his official donkey, waved his hands desperately [52] Lancre was so backward that its population of 500 had only one civil servant, Shawn Ogg, who handled everything from national defence and tax gathering to mowing the castle lawns, although he was allowed help with the lawns. Lawns required care.

.

'It's me, Mistress Weatherwax! I wish you'd stop doing this!' 'See?' said Granny. 'You ain't havin'

another two!' 'No, no, I've just come up to deliver this for you ... ' Shawn waved quite a thick wad of paper. 'What is it?'

'Tis a clacks for you, Mistress Weatherwax! It's only the third one we've ever had!' Shawn beamed at the thought of being so close to the cutting edge of technology.

'What's one of them things?' Granny demanded. 'It's like a letter that's taken to bits and sent through the air,' said Sean.

'By them towers I keep flyin' into?' 'That's right, Mistress Weatherwax.'

'They move 'em around at night, you know,' said Granny. She took the paper.

'Er ... I don't think they do ...' Shawn ventured. 'Oh, so I don't know how to fly a broomstick right, do I?' said Granny, her eyes glinting.

'Actually, yes, I've remembered,' said Shawn quickly. 'They move them around all the time. On carts. Big, big carts. They ...'

'Yes, yes,' said Granny, sitting on a stump. 'Be quiet now, I'm readin'

The forest went silent, except for the occasional shuffling of paper.

Finally, Granny Weatherwax finished. She sniffed. Birdsong came back into the forest.

'Silly old fools think they can't see the wood for the trees, and the trees are the wood,' she muttered. 'Cost a lot, does it, sendin' messages like this?'

'That message,' said Shawn, in awe, 'cost more than 600 dollars! I counted the words! Wizards must be made of money!'

'Well, I ain't,' said the witch. 'How much is one word?'

'Five pence for the sending and five pence the first word,' said Shawn, promptly.

'Ah,' said Granny. She frowned in concentration, and her lips moved silently. 'I've never been one for numbers,' she said, 'but I reckon that comes to ... sixpence and one half-penny?'

Shawn knew his witches. It was best to give in right at the start.

'That's right,' he said.

'You have a pencil?' said Granny. Shawn handed it over. With great care, the witch printed some block capitals on the back of one of the pages, and gave it to him.

'That's all?' he said.

'Long question, short answer,' said Granny, as it if was some universal truth. 'Was there anything else?'

Well, there might be the money, Shawn thought. But in her own localised way, Granny Weatherwax had an academic position in these matters. Witches took the view that they helped society in all kinds of ways which couldn't easily be explained but would become obvious if they stopped doing them, and that it was worth six pence and one half-penny not to find out what these were.

He didn't get his pencil back.

The hole into L-space was quite obvious now. It fascinated Dr.Dee, who was confidently expecting angels to come out of it, although all it had produced so far was an ape.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.