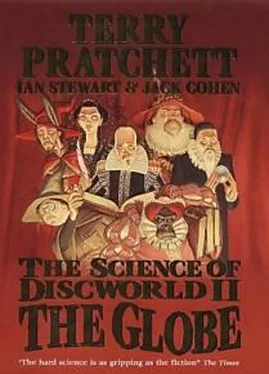

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld II - The Globe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld II - The Globe

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Such people see no need to think about what they are doing, because they base their beliefs on authority. If a question is not raised by that authority, then it's not a question they want to ask.

So, in support of their theories, homeopaths quote Paracelsus: 'That which makes disease is also the cure.' But Paracelsus built his entire career on not respecting authority. Moreover, he never said that a disease is always its own cure.

Contrast this modern spectrum of silliness with the robust, critical attitude of most Renaissance scholars to the idea that arcane practices can lay bare the bones of the world. People such as Dee, indeed Isaac Newton, took that critical position very seriously. To a great extent, so did Paracelsus: for example he repudiated the idea that the stars and planets control various parts of the human body. The Renaissance view was that God's creation has mysterious elements, but those elements are hidden [21] Hidden knowledge at that time was spectacularly practical knowledge, exemplified by the Guild secrets and especially by the Freemasons. It was dressed up in ritual, because it was mostly passed on verbally and not written down.

, implicit in the nature of the universe, rather than arcane.

This view is very close to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek's marvelling at the animalcules in dirty water, or semen: the astonishing discovery that the Wonders of Creation extended down into the microscopic realm. Nature, God's Creation, was much more subtle. It provided hidden wonders to marvel at as well as the overt artistic vision. Newton was taken with the implicit mathematics of the planets in just this way: there was more to God's invention than was apparent to the unaided eye, and that resonated with his Hermetic beliefs (a philosophy derived from the ideas of Hermes Trismegistos). The crisis of atomism at time was the crisis of pre-formation: if Eve had within her all daughters, each having within her her daughters like a set of Russian dolls, then matter must be infinitely divisible. Or, if not, we could work out the future date of Judgement Day by discovering how many generations there were until we got to the last, empty daughter.

A characteristic of Renaissance thinking, then, was a degree of humility. It was critical about its own explanations. This attitude contrasts favourably with such modern religions as homeopathy, Scientology, creeds that arrogantly claim to offer a 'complete' explanation of the Universe in human terms.

Some scientists are equally arrogant, but good scientists are always aware that science has limitations, and are willing to explain what they are. 'I don't know' is one of the great, though admittedly under-utilised scientific principles. Admitting ignorance clears away so much pointless nonsense. It lets us cope with stage magicians performing the beautiful, and very convincing, illusions -convincing, that is, while we keep our brains out of gear. We know they have to be tricks, and admitting ignorance lets us avoid the trap of believing the illusion to be real merely because we don't know how the trick works. Why should we? We're not members of the Magic Circle. Admitting ignorance similarly protects us against mystic credulity when we encounter natural events that have not yet caught the eye of a competent scientist (and his grant- awarding body), and that still seem to be ... magic. We say 'The magic of nature' ... more the Wonder of Nature, or the Miracle of Life.

This is a stance that nearly all of us share, but it's important to understand the historical tradition it is grounded in. It isn't simply a case of admiring the complexity of God's works. It implies the attitudes of Newton, van Leeuwenhoek and earlier; indeed, right back to Dee. And, doubtless, to some Greek, or several. It involves the Renaissance belief that if we investigate the wonder, the marvel, the miracle, then we'll find even more wonders, marvels and miracles: gravity, say, or spermatozoa.

So what do we, and what did they, mean by 'magic? Dee spoke of the arcane arts, and Newton was committed to many explanations that were 'magickal', especially his commitment to action at a distance, 'gravity', which derived from the mystical attraction/repulsion basics of his Hermetic philosophy.

So 'magic' means three things, all apparently quite different. Meaning one is: 'something to be wondered at', and this ranges from card tricks to amoebas to the rings of Saturn. Meaning two is turning a verbal instruction, a spell, into material action, by occult or arcane means ... turning a person into a frog, or vice versa, or a djinn building a castle for his master. The third meaning is the one we use: the technical magic of turning a light switch on, and getting light, without even having to say 'fiat lux'.

Granny Weatherwax's recalcitrant broomstick is type two magic, but her 'headology' is largely a very, very good grasp of psychology (type three magic carefully disguised as type two). It brings to mind Arthur C. Clarke's phrase 'Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic', which we quoted and discussed in The Science of Discworld. Discworld exemplifies magic by spells, and indeed is maintained as an unlikely creation by being immersed in a strong magical field (type two). Adults of Earthly cultures, like Roundworld, pretend to have lost intellectual belief in magic of the Discworld kind, while their culture is turning more and more of their technology into magic (third kind). And the development of Hex throughout the books is turning Sir Arthur on his head: Discworld's sufficiently advanced magic is now practically indistinguishable from technology.

We can see, as (fairly) rational adults, where the first kind of magic comes from. We see something wonderful and feel tremendously happy that the universe is a place that can include ammonites, say, or kingfishers. But where did we get our belief in the second, irrational kind of magic? How does it come about that all cultures have children that begin their intellectual lives by believing in magic, instead of the real causality that surrounds them?

A plausible explanation is that human beings are initially programmed through fairy stories and nursery tales. All human cultures tell stories to their children; part of the development of our specific humanity is the interaction that we get with early language.

All cultures use animal icons for this nursery tuition, so we in the West have sly foxes, wise owls and frightened chickens. They seem to come out of a human dreamtime, where all animals seem to be types of human being in a different skin, and talk as a matter of course. We learn what the subtle adjectives mean from the actions -and words -of the creatures in the stories. Inuit children don't have a 'sly' fox icon; their fox is 'brave' and 'fast', while the Norwegian iconic fox is secretive and wise, full of good advice for respectful children. The causality in these stories is always verbal: 'So the fox said ... and they did it!' or 'I'll huff and I'll puff and I'll blow your house down.' The earliest communicated causality that the child meets is verbal instructions that cause material events. That is, spells.

Similarly, parents and carers are always transmuting the child's expressed desires into actions and objects, from food appearing on the table when the child is hungry to toys and other birthday and Christmas gifts. We surround these simple verbal requests with 'magical' ritual. We require the spell to begin with 'please', and its execution to be recognised by 'thank you' [22] Carers even encourage or berate the child: 'What's the magic word? You forgot the magic word!'

. It is indeed not surprising that our children come to believe that the way to acquire or access bits of the real world is simply to ask -indeed, simply asking or commanding is the classic spell. Remember 'open, sesame'?

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld II - The Globe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.