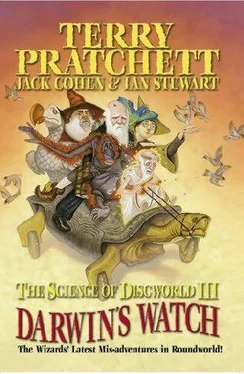

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The central lesson is that although natural selection has a very varied base to work with (recombinations of ancient mutations, differently assorted in all those `waste' progeny), clear large-scale themes emerge. Marine predators, such as sharks, dolphins, and ichthyosaurs all have much the same shape as barracuda, because hydrodynamic efficiency dictates that streamlining will catch you more prey, more cheaply. Very different lineages of planktonic larvae all have long spines or other extensions of the body to restrain the tendency to fall or rise because their density differs from that of seawater, and most of them pump ions in or out to adjust their densities too. As soon as creatures acquire blood systems, other creatures - leeches, fleas, mosquitoes - develop puncture tools to exploit them, and tiny parasites exploit both the blood as food and the bloodsuckers as postal systems. Examples are malaria, sleeping-sickness, and leishmaniasis in humans, and lots of other parasitic diseases in reptiles, fishes, and octopuses.

Large-scale themes may be the obvious lesson, but the last examples reveal a more important one: organisms mostly form their own environments, and nearly all of the important context for organisms is other organisms.

Human social history is like evolutionary history. We like to organise it into stories, but that's not how it really works. History, too, can be convergent or divergent. It seems quite sensible to believe that small changes mostly get smeared out, or lost in the noise, so that big changes are needed to divert the course of history. But anyone familiar with chaos theory will also expect some tiny differences to set off divergent histories, drifting progressively further away from what might have happened otherwise.

Changing history is a theme of time-travel stories, and the two issues come together in those stories called `worlds of if.

We have the strongest feeling that what we do, even what we decide, does change history. If I decide, now, not to go and meet Auntie Janie at the train station even though she's expecting me because I told her I would ... the universe will take a different path from the one it would have taken if I had done the expected. But we've just seen that even saving Abraham Lincoln from the assassin would have the tiniest, most local, of effects. Neighbours such as the gas-bag aliens on Jupiter wouldn't notice Lincoln's survival at all, or at least not for a very long time. After all, we haven't yet noticed them [45] Well, there might be ...

.

In fact, how will they, or we, notice? How will we be able to say, `Just a minute, this newspaper shouldn't be called the Daily Echo ... There must have been a time traveller interfering, so that we're now in the wrong leg of the Trousers of Time'?

Auntie Janie making her own way from the station won't topple empires - unless you believe, with Francis Thompson's The Mistress of Vision, that All things by immortal power Near or far Hiddenly To each other linked are That thou canst not stir a flower Without troubling of a star.

That is, all contingent chaos butterflies are responsible in some sense for all important events like hurricanes and typhoons - and newspaper titles. When a typhoon, or a newspaper tycoon, topples an empire, that event is caused by everything, all those butterflies, that preceded it. Because change in any one - or perhaps just in one of a very large number - can derail the important event.

So everything must be caused by everything before it, not just by a thin string of causality.

We think about causality as a thin string, a linear chain of events, link following link following link ... probably because that's the only way we can hold any kind of causal sequence in our minds. As we'll see, that's how we deal with our own memories and intentions, but none of this means that the universe can isolate such a causal string antecedent to any event at all, important or not. And surely 'important' or `trivial' is usually human judgement, unless the universe really does `smear out' most small changes (whatever that means), and major events are those whose singular influence can be distinguished at later times.

Because they are stories, committed to the way our minds work and not to the way the universe works its own causality, most timetravel stories assume that a big (localised) change is needed to have a big effect - kill Napoleon, invade China ... or save Lincoln. And time travel stories have another convention, another `conceit', because they are stories, nearer fee-fi-fo-fum than physics. This is the remembered timeline of the traveller. Usually the plot depends on it being unique to him. When he comes back to his present he remembers stepping on the butterfly, or killing his grandfather, or telling Leonardo about submarines. .. but no one else is conscious of anything other than their `altered' present.

Let's move from large events, large or small causes, to how we influence the apparent causality in our own lives. We have invented a very strange oxymoron to describe this: `free will'. These words appear prominently on the label of the can of worms called `determinism'. In Figments of Reality we titled the free will chapter: `We wanted to have a chapter on free will, but we decided not to, so here it is' in order to expose the paradoxical nature of the whole idea. Dennett's recent book Freedom Evolves is a very powerful treatment of the same topic. He shows that in regard to `free will' it doesn't matter whether the universe, including humans, is deterministic. Even if we can do only what we must, there are ways to make the inevitable evitable. Even if it is all butterflies, if tiny differences chaotically determine large historical trends, nevertheless creatures as evolved as us can have `the only free will worth having', according to Dennett. He writes of dodging a baseball coming for his face, and this being perhaps a culmination of a causal chain going right back to the Big Bang - yet if it will help his team, he might let it hit his face.

But then, what decides it is: will it help his team? That's not a free choice.

Inevitable, evitable.

Dennett's best example is more ancient: Odysseus's ship approaching the Sirens. Inevitably, if his men hear the Sirens' song, they will steer the ship on to the rocks. But the steersman must be able to hear the surf, so there seems no way to avoid their lure. Odysseus has himself lashed to the mast, while all his sailors plug their ears with wax so they cannot hear the Sirens. The vital issue for Dennett is that humans, and on this planet probably only humans, have evolved several stages beyond the observing-and-reacting that even quite advanced animals do. We observed ourselves and others observing, so got more context to embed our behaviour in - including our prospective behaviour. Then we developed a tactic of labelling good and bad imaginary outcomes, just as we labelled our memories with emotional tags. We, and some other apes - perhaps also dolphins, perhaps even some parrots - developed a `theory of mind', a way to imagine ourselves or others in invented scenarios and to anticipate the associated feelings and responses. Then we learned to run more than one scenario: `But on the other hand, if we did so-and-so, the lion couldn't get us anyway...', and that trick soon became a major part of our survival strategy. So with Odysseus ... and fiction ... and particularly that dissection of hypothetical alternatives that we call a time-travel story.

In our minds, we can hold many possible histories, just as Mead showed that every discovery about today implies a different past leading up to it. But whether there is any sense in which the universe has several possible pasts (or futures) is a much more difficult question. We've argued that popularisations of quantum indeterminacy, particularly the many-worlds model, have got confused about this. They tell us that the universe branches at every decision point, whereas we think that people have to invent a different mental causal path, a different explanatory history, for each possible present or future.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.