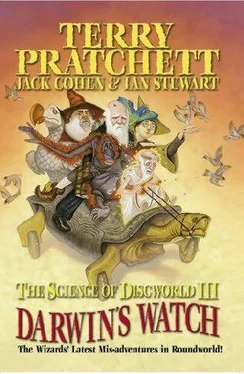

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Wallace hadn't mentioned publishing his theory, but Darwin now felt obliged to recommend it to him. At that point it looked as if Charles had compounded his Really Bad idea, but for once the universe was kind. Lyell, searching for a compromise, suggested that the two men might agree to publish their discoveries simultaneously. Darwin was concerned that this might make it look as if he'd pinched Wallace's theory, worried himself to distraction, and finally handed the negotiating over to Lyell and Hooker and washed his hands of it.

Fortunately, Wallace was a true gentleman (the accident of breeding notwithstanding) and he agreed that it would be unfair to Darwin to do anything else. He hadn't realised that Darwin had been working on exactly the same theory for many years, and he had no wish to steal such an eminent scientist's thunder, perish the very thought. Darwin quickly put together a short version of his own work, and Hooker and Lyell got the two papers inserted into the schedule of the Linnaean Society, a relatively new association for natural history. The Society was about to shut up shop for the summer, but the council fitted in an extra meeting at the last minute, and the two papers were duly read to an audience of about thirty fellows.

What did the fellows make of them? The President reported later that 1858 had been a rather dull year, not `marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionise, so to speak, our department of science'.

No matter. Darwin's fear of controversy was now irrelevant, because the cat was out of the bag, and there was no chance whatsoever that the beast could be stuffed back in. Yet, as it happened, the anticipated controversy didn't quite materialise. The meeting of the Linnaean Society had been rushed, and the fellows had departed muttering vaguely under their breaths, feeling that they ought to be outraged by such blasphemous ideas ... yet puzzled because the enormously respected (and respectable) Hooker and Lyell clearly felt that both papers had some merit.

And the ideas struck home with some. In particular, the VicePresident promptly removed all mention of the fixity of species from a paper he was working on.

Now that Darwin had been forced to put his head above the parapet, he would lose nothing by publishing the book that he had previously decided not to write, but had constantly been thinking about anyway. He had intended it to be a vast, multi-volume treatise with extensive references to scientific literature, examining every aspect of his theory. It was going to be called Natural Selection (a conscious or subconscious reference to Paley's Natural Theology?). But time was pressing. He polished up his existing essay, changing the title to On the Origin of Species and Varieties by Means of Natural Selection. Then, on the insistent advice of his publisher John Murray, he cut out the `and Varieties'. The first print run of 1250 copies went on sale in November 1859. Darwin sent Wallace a complimentary copy, with a note: `God knows what the public will think.'

In the event, the book sold out before publication. Over 1500 advance orders came in for those 1250 copies, and Darwin promptly started working on revisions for a second edition. Charles Kingsley, author of The Water-Babies, country rector, and Christian socialist, loved it, and wrote a lavish letter: `It is just as noble a conception of Deity, to believe that He created primal forms capable of selfdevelopment ... as to believe that He required a fresh act of intervention to supply the lacunas [33] No, not long-haired South American beasts of burden, but Latin for `gaps'.

which He himself had made.' Kingsley was something of a maverick, because of his socialist views, so praise from this source was something of a poisoned chalice.

The reviews, steadfast in their Christian orthodoxy, were distinctly less favourable. Even though Origin hardly mentions humanity, all the usual complaints about men and monkeys, and insults to God and His Church, were trotted out. What particularly galled the reviewers was that ordinary people were buying the thing. It was all right for the upper classes to toy with radical views, it had an attractive frisson of naughtiness and was perfectly harmless among gentlemen of breeding, though not ladies of course; but those same views might put ideas into the common folk's heads, if they were exposed to them, and upset the established order. For Heaven's sake, the book was even selling to commuters outside Waterloo railway station! It must be suppressed!

Too late. Murray geared up to print 3000 copies of the second edition, whose likely sales were not going to suffer from public controversy. And the people who mattered most to Darwin - Lyell, Hooker, and the anti-religious `evangelist' Thomas Henry Huxley - were impressed, and pretty much convinced. While Charles stayed out of the public debate, Huxley set to with a will. He was determined to advance the cause of atheism, and Origin gave him a point of leverage. The radical atheists loved the book, of course: its overall message and scientific weightiness were enough for them, and they weren't too concerned about fine points. Hewett Watson declared Darwin to be `the greatest revolutionist in natural history of this century'.

In the introduction to Origin, Darwin begins by telling his readers the background to his discovery: When on board H.M.S. Beagle, as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts, in the distribution of the inhabitants of South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species - that mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers. On my return home, it occurred to me, in 1837, that something might perhaps be made out of this question by patiently accumulating and reflecting on all sorts of facts which could possibly have any bearing on it.

Apologising profusely for lack of space, and time, to write something more comprehensive than his 150,000-word tome, Darwin then moves towards a short summary of his main idea. Writers on science generally appreciate that it is seldom enough to discuss the answer to a question: it is also necessary to explain the question. And that, of course, should be done first. Otherwise your readers will not appreciate the context into which the answer fits. Darwin was clearly aware of this principle, so he begins by pointing out that: It is quite conceivable that a naturalist, reflecting on the mutual affinities of organic beings, on their embryological relations, their geographical distribution, geological succession, and other such facts, might come to the conclusion that each species had not been independently created, but had descended, like varieties, from other species. Nevertheless such a conclusion, even if well founded, would be unsatisfactory, until it could be shown how innumerable species inhabiting this world have been modified, so as to acquire those perfections of structure and coadaptation which most justly excites our admiration.

Already we see a gesture towards Paley - 'perfections of structure' is a clear reference to the watch/watchmaker argument, and `had not been independently created' shows that Darwin doesn't buy Paley's conclusion. But we also see something that characterises the whole of Origin: Darwin's willingness to acknowledge difficulties in his theory. Time and again he raises possible objections - not as straw men, to be knocked flat again, but as serious points to be considered. More than once he concludes that there is more to be learned, before the objection can be resolved. Paley, to his credit, did something similar, though he didn't go as far as admitting ignorance: he knew that he was right. Darwin, a real scientist, not only had his doubts - he shared them with his readers. He would not have arrived at his theory to begin with if he had failed to seek the weaknesses of the hypotheses upon which it was based.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.