The dogs had halved the distance. Puffs of dust rose from the ground beneath their feet as they closed on him. He jumped into a narrow manhole at the base of the wall and reached up for the grate. The dogs snarled and nipped at his fingers as he slid it back into place. One thrust a paw into the narrowing opening and yelped in pain when the edge of the cover fell on its toes.

The others, realizing that the interloper had effectively escaped, took the only option left open to avenge their comrade: one by one they lifted a leg and pissed through the grate.

“Goddamn!” MacLeod let go and dropped the last meter to escape the shower of urine. The dogs, satisfied that they’d accomplished what they could, trotted away with tails high.

MacLeod cursed under his breath the length of the concrete tube and lay on his back to squeeze under the bars at the outlet where the infrequent rains had eroded the ground beneath their footings. He retrieved his backpack and dragged his tricycle up the bank from its concealment in the bottom of the dry flood channel then set off along the edge of the sterile alkali plain peddling furiously.

He encountered the perimeter road a few minutes later but did not slack off until the road merged into a main thoroughfare a few minutes after that. Satisfied that he’d escaped observation, assuming that the rent-a-cops at the boneyard had even bothered to investigate the ruckus, MacLeod eased into a less exhausting cadence.

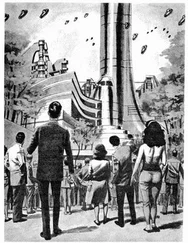

The ground beneath him began to vibrate moments before the sound reached him through the cold, dry air. The powerful low-frequency rumble vibrated the organs within his body as a starship rose from its pad several kilometers distant. MacLeod paid it no mind; he’d seen the same spectacle several times a week for more than twenty years. Of more interest were the other vehicles around him, some so large that they could crush cycle and rider beneath their treads without the driver noticing so much as a bump.

The tempo at God’s Saucer never slacked, save when the rare rainstorms flooded the alpine desert and hydrated the lakebed, turning it into a quagmire within hours. No one complained, though. The soaking hardened the fine dust kicked loose by wheels, tracks and the blast of engines, and filled in the gouges, scrapes and craters left by botched landings and outright crashes.

Cormack encountered no pedestrians other than those walking short distances between vehicles and buildings. Here and there he saw riggers cabling loads for crane hoists and laborers going about any number of activities, all bundled and masked against the cold wind and dust. Those that noticed Cormack stared for a moment wondering what fool risked his life and comfort traveling by cycle, unprotected against the elements.

MacLeod had experienced exposure to worse weather than that at God’s Saucer during his sixty-three years of life. His hide had been baked by innumerable suns, freeze dried by arctic winds, attacked by fungus, radiation and chemicals. The only extra protection he afforded himself when he ventured out was the patch covering his empty left eye socket. Without it the cold penetrated his skull like a knife, leaving him bedridden with headaches that lasted for days.

At last his destination hove into view: a rundown compound consisting of a single building with three sets of rollup doors that doubled as both workspace and living quarters. The hulls of more than two dozen small spacecraft in various stages of cannibalization littered the grounds, one more miniature boneyard among hundreds at God’s Saucer. A high fence of heavy-gauge chain link, crowned by a double coil of electrified razor wire to discourage the type of thievery MacLeod had just committed, surrounded the entire compound.

He coasted to a stop at the gate, punched a code into the electronic cypherlock, and pushed his cycle through as soon as the gate shuddered open enough to let him pass. He repeated the process at the building and doffed the irksome eye patch once the rollup had sealed itself once more behind him.

MacLeod’s shop was as cluttered and messy inside as out. A few custom hull molds leaned against the rear wall surrounded by numerous machining tools. Power hand tools, cutting torches and grinding devices, electronic test equipment and tangles of wire and circuit boards lay scattered about the workbenches along the walls. The only comparatively clear space was that immediately around his latest and recently completed project: a ten-meter-long baffle-rider resting on a stout timber cradle. He’d spent the better part of three months rebuilding the badly damaged ship and though he was pleased with the result, pleasure didn’t make up for the fact that the ship’s owner had stiffed him.

Finding a buyer was only a matter of time: MacLeod was known in certain circles for the quality of his work and his abhorrence of paperwork and regulations. Still, he’d been saddled with a number of bills and it wasn’t as if he could just pack up and disappear to escape his creditors.

He pushed aside a pile of clutter on one bench and dumped out the contents of his backpack in its place, then headed for his sparse living quarters to prepare his evening meal. He broke the seal on one of the long-expired space rations he subsisted on and turned to a cupboard where he kept his vids while it heated. Hugh Jorgan and the Space Nymphs , he decided.

MacLeod carried the vid disk and space ration to the only furniture he owned: a high-resolution tri-dee projector and a pilot’s couch he’d salvaged from a long-range scout craft several years earlier. He settled into the chair’s aerogel padding contentedly and activated the built-in heat massage. Before long he was laughing uproariously while Hugh Jorgan engaged in an astounding number of dalliances with a bevy of vacuum-breathing nymphomaniacs bent on enslaving mankind with kinky sex.

A buzzer over one of the rollups cawed. It repeated its call every few seconds while MacLeod crossed to the personnel door. He killed the interior lighting and cracked it open a few centimeters. A lone figure supporting itself with the aid of two canes stood at his outer gate, illuminated by the single overhead floodlight. The figure reached out carefully, as a man perched atop a tall pole and fearful of falling might, and pushed the button mounted on the fence again.

“I hear ye!” MacLeod shouted when the bone-rattling sound of the buzzer finally cut out. “We’re closed!”

The man said something, his voice drowned out by the scream of an engine test somewhere out on the lakebed. The budding confrontation paused until the test ran its course and the man repeated himself.

“I come for my ship!”

Cormack recognized him, then: it was Stoyko, the owner of the small ship in his shop. Until that moment MacLeod’s dealings with the man had been by vidcom. The spacer seemed to have aged twenty years in the two weeks since they’d last spoken. Too much time in space without gravity had atrophied even his facial muscles, which sagged under the unaccustomed physical strain.

“Then you come with money, I expect.”

Stoyko looked down ashamedly. “I told you before I got no money.”

“An’ I told ye I ain’t a charity,” MacLeod yelled back. “I’m out o’ pocket a hundred thousand euros an’ more. No money; no ship!”

“I got trade,” the man offered hopefully.

“What sort o’ trade?”

The man leaned on one cane and beckoned to him as he reached down to open a bag at his feet. MacLeod approached cautiously, staying to the shadows until he was sure the object wasn’t a weapon. He wouldn’t have ventured out in most circumstances, but the spacer could barely hold himself upright and decalcification had weakened his bones. Though twenty years his senior, Cormack knew he could break his arms with no effort at all. He peered through the fence at the object.

Читать дальше