Nathaniel had light hair with a shiny, sculpted look that most of the boys sported. Glasses. He wore a dark tie, white shirt and dark jacket. Varsity track. Art club. She thumbed through the annual. Grainy black and white photos of football games and victory gardens. At the homecoming dance, several boys were in uniform. Some downtown Harriston buildings in the background of the homecoming parade were familiar.

Prom pictures were in a copy of the school paper, The Lions Roar , stuck in the back of the book. On the second page, she found Nathaniel, his arm around a pretty girl with dark hair like her own, but curled instead of straight, hanging to her shoulders instead of trimmed to just under the ears. The caption read, “The Prom’s best couple: Junior Nathaniel Shirley and Senior Erica Weiss.”

Meadoe went back to her computer. If Nathaniel did the wall art, he didn’t enjoy it long before he died. Why did people move in and out of her house so often? Thoughtfully she typed in a search for “ghosts and poltergeists.” Her research offered numerous explanations for ghosts and hauntings. One source suggested that ghosts wanted attention. That’s why so many of them threw things. Another argued that poltergeist phenomena was caused by the emotional upheaval of someone in the house, generally a pre-adolescent girl. Was she effectively pre-adolescent? Could her house be responding to her? One ghost hunter said ghosts recreated the circumstances that held them to the earth. Another maintained ghosts existed because they had unfinished business.

In the August ’45 Harriston Independent , on the second to last page, she found Nathaniel under the headline, “Truck Strikes Local Youth.” He’d been crossing the intersection of Harriston Boulevard and Broadway when a milk truck hit him. The paper reported Nathaniel died at St. Joseph hospital that afternoon of head injuries. Beside the article was the same class picture she’d seen in the yearbook looking so formal, so young in his coat and tie.

Before going home, she stopped at the video store.

“Do you carry The Outlaw , with Jane Russel?” Meadoe asked.

The teen cashier keyed the title into his computer and shook his head.

“ Four Jills in a Jeep ?” On the wall beside her, Meadoe counted at least 60 copies of the latest release. “How about The Haunted Honeymoon or Destination Tokyo ?”

“Nope.” He hit a key that brought up more information about the films. “Jeeze, those are old. You’d probably have to order them special.”

“ Casablanca ?”

“That we have. Two copies. The film’s in black and white though. I’m supposed to tell you that because some guy rented it last year and raised a stink because he thought it was defective.”

At home she phoned Joan. “I’ve got curtains to put up you can help with, and a video to watch if you aren’t doing anything.”

“I’ll bring wine,” Joan said.

In the middle of the afternoon, the whole ghost theory seemed suspect. Certainly the apparition in the window could have been her imagination, and maybe she’d messed up her own clothes in the dresser in the middle of the night. She’d never done that before, but she’d never moved into a house of her own either, nor had she had night sweats.

Which was Joan’s point an hour later as they hung the bedroom curtains. “There’s numerous medical reasons for profuse sweating. You’re young for it, but it could be early signs of menopause.”

Joan pushed a hook into the drape’s back while Meadoe held the fabric up. None of the windows were standard width, and the curtains really should have been special ordered, but Meadoe couldn’t afford that. Custom curtains were on the lengthening list of home improvements. She tried to keep her tone light. “Oh, no. It couldn’t be that. My grandmother had a child when she was forty-three.” A medical condition? she thought. Her father spent four months in a hospital dying of colon cancer when she was twelve. She remembered how frail his arms became—how thin his face. Cancer killed her grandfather too. Slow mushroom clouds erupted in his lungs, a part of Hiroshima’s omnipresent past.

Joan took three hooks from her chest pocket and moved down the drape, pushing each one in. “That’s the benign explanation. Anxiety provoked by severe repression could cause it too—a purely psychological symptom—but night sweats can accompany diabetes, M.S., AIDS, polio and a half dozen other things I can’t think of off the top of my head. First things first, we ought to get your estrogen checked.”

In Meadoe’s bedroom, Joan examined the wall for a long time, touching some of the pictures, then moving back with her head cocked, as if she were in an art gallery. “Whew! And you think this was all done by a sixteen-year-old?”

“No more than a month before he died.” Now that Meadoe had seen the pattern that drew her eye to Tokyo Rose, it seemed it should be obvious to Joan too, but Joan didn’t seem to notice it.

“I always liked ’40s hair styles. They struck me as more… deliberate. This low maintenance look we all go for now just isn’t as romantic. There must be a half a can of hair spray on that woman’s head. Oh, look at that.” She had found Tokyo Rose. “She looks a little like you, Meadoe. Did you notice that? She’s beautiful.”

“We all look alike to you.” Meadoe laughed.

“There’s more of the west in you than the east, girl.” Joan put a stool under the curtain rod and hung the drapes. “There, now you won’t be wondering about peeping Toms in the shrubbery.”

Over a glass of wine, Meadoe told Joan about her scare the night before and the dream. Meadoe looked into her glass as she spoke. Remembering the touch on her back raised new goosebumps. She could still feel the fingers over her skin.

“Doesn’t the timing of these things strike you as fortuitous?” said Joan. “I mean, it’s pretty obvious that the evening I bring up a delicate topic in our session—ask you what you fear most—your subconscious supplies fears. Of course, the face in the window is symbolic in some way. It could be your repressed self looking out at you, or it could be Christopher Towne coming back in your imagination.” Joan laughed. “Or it could have been a funny trick of light. Not everything has a psychological explanation. The dream now, that is interesting. What were you wearing in it?”

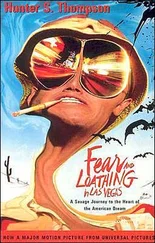

Meadoe shook Casablanca from its plastic box and put it in the VCR. “I don’t know. I suppose a bathing suit. He touched bare skin.”

Joan settled onto the couch after slipping a coaster under her wine glass. “How do you know that he was a he? You said you only saw feet.”

“I… I don’t know that either. In the dream I assumed it was a man.”

Meadoe sat on the couch. Joan moved over to accommodate. It was more of a love seat than a proper couch, not large enough for Meadoe to stretch out to take a nap on.

“And you said when he touched you in the dream you liked it? I’d say that was a good sign. It’s obvious the dream has sexual overtones, and you welcomed them.”

“The sun was hot. I was burning up, and his hand was cool. Do we have to talk about it? The movie has started.”

Black and white maps appeared on the screen with a voice over. Lines traced a path through Europe to Casablanca. The narrator said of refugees without visas in Casablanca that their fate was to “wait and wait and wait.” She thought about Nathaniel Shirley. What if he was a ghost in this house, caught in his sixteenth year, and like the refugees, looking for a way to escape?

An Englishman wearing a monocle said, “We hear very little, and we understand even less.” Meadoe nodded. That made sense. She hadn’t seen Casablanca before, and it struck her as funny. The music seemed overstated, and the acting stilted. A plane flying in one scene was clearly a model, and the Germans were stereotypical. She wondered how Japanese were portrayed in other films from that era.

Читать дальше