“Wait, so there were ghosts?” Gwenda said.

“Liam said there were. He said he never saw them, but later on, when he lived in other places, he realized that there must have been ghosts. In both places. Both houses. Other places just felt empty to him. He said to think of it like maybe there was this kid who grew up in the middle of an eternal party, or a bar fight, one that went on for years, or somewhere where the TV was always on. And then you leave the party, or you get thrown out of the bar, and all of a sudden you realize you’re all alone. Like, you just can’t get to sleep without that TV on. You don’t sleep as well. He said he was always on high alert when he was away from the murder house, because something was missing and he couldn’t figure out what. I think that’s what I picked up on. That extra vibration, that twitchy radar.”

“That’s sick,” Sullivan said.

“Yeah,” Sisi said. “That relationship was over real quick. So that’s my ghost story.”

Mei said, “How long were you in the house?”

“I don’t know, about two hours? He’d brought a picnic dinner. Lobster and champagne and the works. We sat and ate at the kitchen table while he told me about his rotten childhood. Then he gave me the whole tour. Showed me the stains and all, like they were holy relics. I kept looking out the window and seeing the sun get lower and lower. I didn’t want to be in that house after it got dark.”

“So you think you could describe one of the rooms, the living room, maybe, to Maureen? So she could re-create it?”

“I could try,” Sisi said. “Seems like a bad idea, though.”

“I guess I’m just wondering about how that artist made a haunted house,” Mei said. “If we could do the same here. We’re so far away from home, you know? Do ghosts travel this far? I mean, say we find some nice planet. If the conditions are suitable, and we grow some trees and some cows, do we get the table with the ghosts sitting around it? Are they here now?”

Maureen said, “It would be an interesting experiment.”

The Great Room began to change around them. The couch came first.

“Maureen!” Gwenda said. “Don’t you dare!”

Portia said, “But we don’t need to run that experiment. I mean, isn’t it already running?” She appealed to the others, to Sullivan, to Aune. “You know. I mean, you know what I mean?”

“What?” Gwenda said. “What are you trying to say?” Sisi reached for her hand, but Gwenda pushed away from her. She wriggled away like a fish, her arms extended to catch the wall.

On the one hand, The House of Secrets and on the other, The House of Mystery .

About “Two Houses”

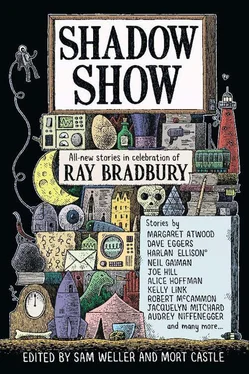

When I was ten or so, I was a student at Westminster Christian Academy in Miami, Florida. There was a school library, and I remember discovering The Illustrated Man there, on a spinning rack. I’d read fantasy novels before—Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Le Guin—and I’d read the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. But I’d never read stories like this before. They took place in a world that I recognized. The characters’ lives were familiar to me. But the things that happened to them were marvelous, terrifying, haunting. Those stories have lived inside my head ever since. They’re part of my DNA. I love Ray Bradbury’s stories, his language, his ideas, his characters—the married couple who run away from the war, the murderous baby, the lodger with the mysterious insides. I love his astronauts, and the mortal boy born into an immortal family. I love his witches, his Martians, his psychologists, and all of his characters who make regrettable bargains.

It was hard to start writing a story for this anthology, because once I started to revisit some of my favorite Bradbury stories, I wanted to keep on reading. I don’t have much to say about “Two Houses.” One of the ghost stories was told to me by the writer Christopher Rowe. The other was lent to me by the writer Gwenda Bond. Thanks to both of them, and of course, and always, to Ray Bradbury.

—Kelly Link

WEARINESS

Harlan Ellison ®

Very near the final thaw of the Universe, the last of them left behind, the last three of the most perfect beings who had ever existed, stood waiting for the transitional moment. The neap tide of all time. The eternal helix sang its silent song in stone; and the glow of What Was to Come had bruised itself to a ripe plumness.

The ostren fanned itself. Melancholia had shortened it; one entire set of faculties could do nothing but sigh. And it had grown uncommonly warm for her, in sight of the end.

The velv could not contain his trepidation, peering out around the perplexing curvature of space.

But the tismess, that being who had summoned the helix, knew boldness was required, here and now at the final moments. And it stood boldly forth, waiting for the inevitable. All three—there were no others—were at the terminus of uncountable multiple trillions of aeons, and weary.

Heaviness hung, a dire swaddling.

“What is there to fear?” the tismess said, rather more nastily than it had intended. Reify, it had thought, urgently.

Heaviness hung, undiminished.

“What is there to fear?” Again, trying to flense the tone of nastiness, chagrined at its incivility, the velv whimpered and stared at the great helix, receptors clouding as the brightness fattened. The point of alarm had been reached and abandoned long since. “I am the last,” it said.

“As is each of us,” thought the ostren. “We are, each of us, you and you each, we are, each of us, the end of the line. Out of time, all time, the last. But why are you frightened?”

“Because… it is the end. The question at last answered. There will be no more. No more I, no more you, no more of any living species. Does that not terrify you?”

“Yes,” thought the ostren. “Yes. Yes, it does.”

The tismess was silent.

And the great helix solidified, its colors steadied, and the last three stared as only they were able, looking into the future, for the past and present were now gone, looking to see what would overwhelm them as they were vaporized, gone like their kind, gone forever, not even motes, not even memories. And they saw, the three last, absolutely perfect beings; they saw what was to come.

“Oh, how good,” whispered the velv, her tissues roiling most golden. “How wonderful. And I’m not afraid… not now.”

The ostren made the sound that very little children had once made when they had truly learned where the puppy farm is. But there was no fear, either, in the ostren.

For the tismess, as it was all coming to an end, suddenly there was what there was to be seen.

What was on the other side.

Before him, immediately before him, was the darkness. Heavy, breathing yet silent, it seemed to go on forever. But that was the other side. And beyond that darkness was something: something he could call the “other side.” Could he see it, could he even imagine it, there had to be another side beyond this side. He reveled in the moment of knowledge that all there had ever been would go on, would start anew perhaps, would roll on through the final night, no matter how long. There was an “other side.”

But of course, in truth, what he was seeing was only another aspect of the only darkness—and not even darkness; nothing.

What he was seeing was every thought he had ever had, every song he had ever sung, everyone he had ever known, every moment of his trillion aeons never knowing he had nowhere else to go, all and everything of memory; where he had stood, what he had done and what had been done around him, what there was and what there could ever have been.

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)