So, again, we say: Come to Earth! We get millions of visitors a year, from near and far. Some of you come by accident. No shame in that! We don’t care if you are just stopping to refuel, or if you lost your way, or even if you just want to rest for a moment and eat a sandwich and drink a cold bottle of beer. We still have beer! Of course, we prefer if you come here intentionally. Many of you do. Many of you read about this place in a guidebook, and some of you even go out of your way and take a detour from your travels to swing by the gift shop. Maybe you are coming because you just want to look, or to say you were here. Maybe you are coming to have a story to tell when you get back. Maybe you just want to be able to say: I went home. Even if it isn’t home, was never your home, is not anyone’s home anymore, maybe you just want to say, I touched the ground there, breathed the air, looked at the moon the way people must have done nine or ten or a hundred thousand years ago. So you can say to your friends, if only for a moment or two: I was a human on Earth. Even if all I did was shop there.

About “Earth (A Gift Shop)”

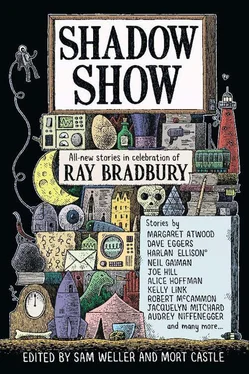

The Ray Bradbury story that inspired me was “There Will Come Soft Rains,” which is about a fully automated house that is still running all of its domestic routines after its human inhabitants have all perished. I was drawn to the idea of telling a story about people through their technology. We can imagine the morning rush of the family who lived in this house: up out of bed, into the shower, down the stairs for toast and oatmeal, coffee for the parents, out the door to face the day at school and work. Our technology will outlive us (unless, of course, we all become cyborgs, in which case I suppose we will become our technology), and future archaeologists will write research papers on their discoveries of the cultural artifacts we are leaving behind.

In my story, I wanted to imagine what it would be like to look at our artifacts now, as outsiders, in a kind of real-time archaeology, or self-anthropology. The artifacts I invent are a bit exaggerated, but not much. Shopping at a mall or theme park these days, I am amazed at how skilled we are at “productizing” things, and I imagine what these packaged cultural products will look like to people a few hundred years from now. In trying to come up with somewhat silly ideas for products, it struck me (not for the first time) how prescient Mr. Bradbury was, how amazing it is that he came up with the “parlor walls” of Fahrenheit 451 almost sixty years ago(!), and now we can go to the local big-box retailer and buy a high-definition 52-inch flat-screen parlor wall for five or six hundred dollars.

—Charles Yu

HAYLEIGH’S DAD

Julia Keller

Hayleigh and Sharon were forbidden to play in the basement. Hayleigh’s dad, Ed Westin, had been uncharacteristically severe on that point. “Never, never, never, ” he said, inserting a sudden dark barb of seriousness into his otherwise mild voice, to indicate that he meant business, “play in the basement, girls. Got it?” He could be a teaser, a clown; he was definitely one of those “fun dads” whom Sharon deeply, silently admired—her own father, Larry Leinart, being a sour, dreary, disapproving man who seemed to nurse a secret grudge throughout his day, touching it constantly with his thoughts the way you bump a sore finger against everything you reach for—but on the subject of the basement, Hayleigh’s dad was not fun at all. He was firm. Borderline scary.

“Are we totally clear on that, kids?”

They nodded. Not in unison: Hayleigh nodded first, because this was, after all, her house and her dad, and then Sharon joined in.

“So we’re clear,” Ed Westin reconfirmed. His face was blank. No smile crossed it, which was unusual; he had a permanent wrinkle on each side of his mouth, just from smiling so much. At this moment Hayleigh’s dad reminded Sharon of her own father—hard and mean—although Sharon could tell that Mr. Westin’s mood was prompted by concern for their safety, so she forgave him. And anyway, most of the time Hayleigh’s dad was nothing like her dad, in all kinds of ways. Ed Westin was short and kind of pudgy. The girls had discussed this clinically, neutrally, not cruelly. Larry Leinart was tall and slender, with a narrow waist and wide shoulders. His dark suits fit him perfectly, like animal skin.

In a way, Sharon had often thought, it was the reverse of how things ought to be. Ed Westin was the one you’d think would be sleek and solid, because he worked outside with his hands. He was an electrician for Cozad Brothers Construction. Larry Leinart sat behind a desk all day; he was a lawyer with a big law firm downtown. However, as Sharon had been quick to point out to Hayleigh, her father didn’t handle interesting cases involving murders or kidnappings. Instead he focused on things such as corporate mergers and property transfers. No wonder he was so glum all the time. His work was boring and he had to dress up for it. Suit, tie, stiff white shirt, loafers. Whereas Hayleigh’s dad got to wear jeans and a flannel shirt and boots and a baseball cap.

Sharon and Hayleigh had both turned eight years old that fall. They had not been best friends very long. Friendship was a serious thing, with clear, grimly implacable rules. Everybody had one and only one best friend, and that person had to be chosen as your companion every single time , on the playground at recess, or eating lunch in the cafeteria, or whatever.

Sharon had always wanted to be friends with Hayleigh Westin, but until recently, it just hadn’t been possible. Hayleigh’s original best friend was a thin, quiet girl named Samantha Bollinger, and Sharon’s original best friend was actually a boy: Greg Pugh. Normally the gender rule for best friends was absolute—girls with girls, boys with boys—but Greg’s family had lived next door to Sharon’s family since before either Sharon or Greg was born, and he and Sharon had been playing together since they were toddlers, so they got a pass. They were best friends through the first and second grades and the first part of the third.

Then Samantha Bollinger’s parents split up and she and her mother left town. It was very sudden, and to Sharon’s delight, it left Hayleigh without a best friend. Sharon was happy to fill the void. Greg Pugh was on his own now.

A few times that fall, when Hayleigh and Sharon were bored, they would ride their bikes slowly past Samantha’s old house—it was two streets over from Hayleigh’s house—and let their eyes slide over in that direction. Samantha’s dad still lived there, all by himself. If he happened to be getting into his car at the time and spotted them, he would glare. Once, he started to raise his fist, as if he wanted to shout something, but then seemed to get hold of himself. He lowered his fist. He was a mean dad, Sharon instantly realized, not a fun dad.

Samantha’s house didn’t look the same anymore. No bike lay on its side on the front lawn, its tires still spinning because it had been flung away moments ago by Samantha when she raced inside for a juice box. The curtains in the window of what had been Samantha’s bedroom weren’t pink anymore. Her dad must’ve changed the curtains. The house seemed to breathe sour air in and out too slowly, like an old person with respiratory problems.

Samantha had been a runner, the best runner in school, with long legs that moved with such natural grace that she didn’t even seem to be trying; it looked as if running was a normal state for her, like walking is for other people. Yet once Samantha was gone, she was gone, almost as if she’d been running somewhere at dusk one evening and had just kept right on going, her long, thin body merging with the purplish pink twilight, folding herself into it, like somebody leaving the stage of the school auditorium and slipping between the heavy pleats of the curtain, and after a slight stir in the fabric— poof , that’s it. Gone.

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)