Until this summer Abbey felt that nothing could touch the people close to her. Then she had started worrying, and once she’d started she found she couldn’t stop. “Don’t worry about any of Lowell’s predictions. He seems like a big liar.”

“I don’t know.” Bobby looked younger than his years. “My father didn’t get out of bed today.”

At the pool the next day, Cate kept to herself. A light rain started to fall in the afternoon, and when the swimmers scattered into the locker room Cate just sat there on the concrete, rain streaming down. She looked like a water nymph, a creature who belonged to another element.

“You’re going to get soaked,” Abbey called as she scrambled to find a dry place under the patio awning.

“It’s only rain,” Cate said, as if the world around her didn’t matter, as if she was already in some other, unreachable place, a realm much farther away than California.

Once she was underneath the awning, Abby started reading, and soon she was in another world herself. Then, all at once, she felt someone was drowning, even though there were no swimmers in the pool. When she looked up Cate was gone. There was that chill, right through her sweatshirt. She waited, anxious and ready to bolt, until all of the campers were picked up by their parents, then she took off running. The rain was coming down harder. She climbed the fence, snagging her fingers on the metal, then ran along the creek, now rushing with rising water. She imagined him gone; she willed it with all her might. But his tent was still in the field, and there were wisps of smoke from a bonfire that had been doused by the torrents. She went within feet of the tent and called, “Cate?” in a low, shaky tone, but there was no answer and she couldn’t tell if anyone was in the tent, if what she heard was a girl’s voice or only the sound of the rain.

The next morning Cate wasn’t waiting on the corner where they usually met. There were several police cars circling the neighborhood. In a panic Abbey ran all the way to the pool. She had a dark premonition and was quick to berate herself for not warning Cate against Lowell. An angel, a liar, a man with black gloves. But there was Cate, calmly teaching the youngest swim group how to dog-paddle.

“Where were you?” Abbey said as she came up beside her. There was the thrum of panic in her throat as she spoke.

Cate kept her attention focused on the Guppies. “Kick,” she called out to them before she turned to her friend. “We don’t have to do everything together, do we? Anyway, you were the one who was late.”

All that day Cate avoided her, but at their lunch break, Abbey made a point of sitting beside her at the picnic table. “He’s not even Bobby Marcus’s cousin.”

Cate coolly appraised her as she continued eating her lunch. “I know.” Her wet hair streamed down her back.

“And he’s a thief,” Abbey said.

Cate threw her a contemptuous look. “You think you’re so smart.”

“Were you with him when I came looking for you yesterday?” Abbey’s voice sounded broken even to herself.

“He said you’d be jealous.”

“You think I’m jealous?” Abbey stood up, her heart hitting against her chest.

Cate shrugged. “You tell me.”

“Did he tell you Bobby’s father kicked him out? That he stole a car in California?”

“He told me everything,” Cate said calmly. “He told me you can’t be friends with someone who’s filled with envy.”

“Is that what he told you about the future? That we wouldn’t be friends anymore?”

“He said I’d be leaving for California before I knew it.”

Late in the afternoon Abbey told the head counselor that she felt ill and needed to go home. It wasn’t exactly a lie. She packed up her swimsuit and her books and left early, her head throbbing. She walked to the field, then scaled the fence. She stood beside the creek. She wasn’t surprised by what she saw. There was now a car parked under the bushes, hidden by briars and leaves. You had to squint to see it beyond the tree, then it was possible to make out the Marcuses’ old station wagon, which Bobby’s father had reported missing that morning. That was why there were police cars patrolling earlier in the day, looking for signs of the thief.

For a moment Abbey thought she might bolt and run, then keep on running till she reached the far side of the field. Instead, she studied the stolen car, the briars, the field she had come to all her life. She thought about the items he’d taken from the Marcuses’ garage—the tape, the ropes.

He was there, under the tree. He laughed when he saw her, and waved her over. He was graceful and tall and sure of himself. She walked through the high grass, and it stung when it hit against her legs.

“I knew you’d show up,” he said when Abbey reached his campsite. “You and I made a connection. She thinks she’s the one that everyone wants, but it’s you. I can see what’s beautiful about you.” He cupped Abbey’s chin and studied her face. She understood how he could make someone feel special.

Abbey saw then that he was older than they’d first thought, not seventeen or eighteen but in his mid-twenties. There were feathers around the campsite because he was trapping birds for his supper. There were the bones of sparrows and larks, white and stripped bare. She thought about the children who believed an angel had fallen into the field, convinced that a miracle would soon occur. She thought about the volumes in the library that were waiting for her on the shelves, each one beautiful, each one-of-a-kind.

He kissed her and she let him. Soon enough someone would notice the stolen car. He wouldn’t keep himself hidden in this town; he’d have use for the ropes, the tape, the axe, all that he’d need to take someone with him tonight. Maybe he’d stop in a field far from here, in another town, where a girl’s body wouldn’t be identified; maybe he’d keep on driving. He kissed her and she kissed him back. She knew that Cate would follow her into the field, and that she’d spy them together, then turn and run, distraught.

When he grabbed Abbey to pull her toward the car, she slipped out of his grasp, leaving him holding on to nothing but her backpack full of books. She was wearing shorts and a sweatshirt and the sneakers her mother told her were unfashionable. She ran home as if she were the angel with black wings, and she didn’t climb out her window again after that. In fact she kept it locked. She knew that Cate would cry all that night and that she’d never talk to Abbey again, just as she knew that years later, when Cate came home for a visit from California, compelled to stop at the library to confront her old friend, demanding to know how she could have betrayed her so easily, Abbey would simply tell her that the man in the field wasn’t the only one who could see the future.

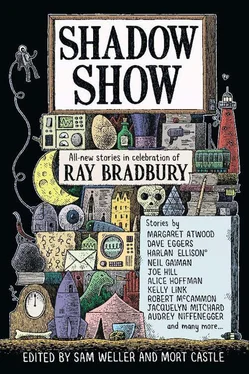

For Ray Bradbury

About “Conjure”

Ray Bradbury’s masterwork, Fahrenheit 451 , a hymn to books and to the power of literature, is a classic work of American fiction and one of the most important books of our lifetime. In a series of novels, short stories, and linked short stories, Bradbury has created his own genre, one that has greatly influenced American literature. Due to his work, magic is no longer corralled into genre writing. It is everywhere in American fiction. Critics may call it magic realism, but it’s simply what Ray Bradbury has been doing from the start.

Bradbury’s themes of innocence and experience echo a world made up of equal parts of dark and light, where characters yearn for both the future and the past and where loss is inevitable. Bradbury has given readers a singular vision of small-town American life, one in which a dark thread is pulled through the grass. Bradbury’s blend of suburban magic rejoices in the American dream, but it also presents the twilight world of darker possibilities, the opposing nightmare.

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)