She fetched the drawing pad out of the water and looked at the green pony with a kind of ringing sickness in her, a feeling like she wanted to throw up. She ripped the pony out and crushed it and threw it into the water. She ripped some other ponies out and threw them too, and the crushed balls of paper bobbed and floated around her ankles. No one told her to stop, and Heather did not complain when Gail let the pad fall out of her hands and back into the lake.

Gail looked out at the water, wanting to hear it again, that soft foghorn sound, and she did, but it was inside her this time, the sound was down deep inside her, a long wordless cry for things that weren’t never going to happen.

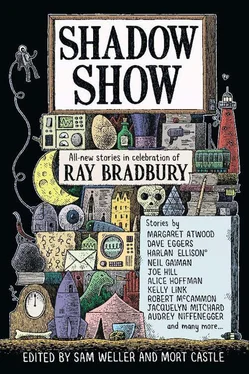

About “By the Silver Water of Lake Champlain”

You don’t wear your strongest influences like a shirt, something you take on and off as you like. You wear those influences like your skin. For me, Ray Bradbury is that way. From the time I was twelve to the time I was twenty-two, I read every Bradbury novel and hundreds of Bradbury short stories, many of them two and three times. Teachers came and went; friends ran hot and cold; Bradbury, though, was always there, like Arthur Conan Doyle, like my bedroom, like my parents. When I ruminate about October, or ghosts, or masks, or faithful dogs, or children and their childish frightening games, every thought I have is colored by what I learned about these things from reading Ray Bradbury. One of Bradbury’s most famous collections is The Illustrated Man , which features a man tattooed with a countless number of Ray’s stories, a man who walks through life carrying all those stories on his back. I relate.

—Joe Hill

First of all, here are the highways of America. Here are the states in sky blue, pink, pale green, with black lines running across them. Peter has a children’s version of the map, which he follows as they drive. He places an X by the names of towns they pass by, though most of the ones on his old map aren’t there anymore. He sits, staring at the little cartoons of each state’s products and services. Corn. Oil wells. Cattle. Skiers.

Second, here is Mr. Breeze himself. Here he is behind the steering wheel of the long old Cadillac. His delicate hands are thin, reddish as if chapped. He wears a white shirt, buttoned at the wrists and neck. His thinning hair is combed neatly over his scalp, his thin, skeleton head is smiling. He is bright and gentle and lively, like one of the hosts of the children’s programs Peter used to watch on television. He widens his eyes and enunciates his words when he speaks.

Third is Mr. Breeze’s pistol. It is a Glock 19 nine-millimeter compact semiautomatic handgun, Mr. Breeze says. It rests enclosed in the glove box directly in front of Peter, and he imagines that it is sleeping. He pictures the muzzle, the hole where the bullet comes out: a closed eye that might open at any moment.

Outside the abandoned gas station, Mr. Breeze stands with his skeleton head cocked, listening to the faintly creaking hinge of an old sign that advertises cigarettes. His face is expressionless, and so is the face of the gas station storefront. The windows are broken and patched with pieces of cardboard, and there is some trash, some paper cups and leaves and such, dancing in a ring on the oil-stained asphalt. The pumps are just standing there, dumbly.

“Hello?” Mr. Breeze calls after a moment, very loudly. “Anyone home?” He lifts the arm of a nozzle from its cradle on the side of a pump and tries it. He pulls the trigger that makes the gas come out of the hose, but nothing happens.

Peter walks alongside Mr. Breeze, holding Mr. Breeze’s hand, peering at the road ahead. He uses his free hand to shade his eyes against the low late-afternoon sun. A little ways down are a few houses and some dead trees. A row of boxcars sitting on the railroad track. A grain elevator with its belfry rising above the leafless branches of elms.

In a newspaper machine is a USA Today from August 6, 2012, which was, Peter thinks, about two years ago, maybe? He can’t quite remember.

“It doesn’t look like anyone lives here anymore,” Peter says at last, and Mr. Breeze regards him for a long moment in silence.

At the motel, Peter lies on the bed, facedown, and Mr. Breeze binds his hands behind his back with a plastic tie.

“Is this too tight?” Mr. Breeze says, just as he does every time, very concerned and courteous.

And Peter shakes his head. “No,” he says, and he can feel Mr. Breeze adjusting his ankles so that they are parallel. He stays still as Mr. Breeze ties the laces of his tennis shoes together.

“You know that this is not the way that I want things to be,” Mr. Breeze says, as he always does. “It’s for your own good.”

But Peter just looks at him, with what Mr. Breeze refers to as his “inscrutable gaze.”

“Would you like me to read to you?” Mr. Breeze asks. “Would you like to hear a story?”

“No, thank you,” Peter says.

In the morning there is a noise outside. Peter is on top of the covers, still in his jeans and T-shirt and tennis shoes, still tied up, and Mr. Breeze is beneath the covers in his pajamas, and they both wake with a start. Beyond the window there is a terrible racket. It sounds like they are fighting or possibly killing something. There is some yelping and snarling and anguish, and Peter closes his eyes as Mr. Breeze gets out of bed and springs across the room on his lithe feet to retrieve the gun.

“Shhhh,” Mr. Breeze says, and mouths silently: “Don’t. You. Move.” He shakes his finger at Peter— no no no!— and then smiles and makes a little bow before he goes out the door of the motel with his gun at the ready.

Alone in the motel room, Peter lies breathing on the cheap bed, his face down and pressed against the old polyester bedspread, which smells of mildew and ancient tobacco smoke.

He flexes his fingers. His nails, which were once long and black and sharp, have been filed down to the quick by Mr. Breeze— for his own good, Mr. Breeze had said.

But what if Mr. Breeze doesn’t come back? What then? He will be trapped in this room. He will strain against the plastic ties on his wrist, he will kick and kick his bound feet, he will wriggle off the bed and pull himself to the door and knock his head against it, but there will be no way out. It will be very painful to die of hunger and thirst, he thinks.

After a few minutes Peter hears a shot, a dark firecracker echo that startles him and makes him flinch.

Then Mr. Breeze opens the door. “Nothing to worry about,” Mr. Breeze says. “Everything’s fine!”

For a while, Peter had worn a leash and collar. The skin side of the collar had round metal nubs that touched Peter’s neck and would give him a shock if Mr. Breeze touched a button on the little transmitter he carried.

“This is not how I want things to be,” Mr. Breeze told him. “I want us to be friends. I want you to think of me as a teacher. Or an uncle!

“Show me that you’re a good boy,” Mr. Breeze said, “and I won’t make you wear that anymore.”

In the beginning Peter had cried a lot, and he had wanted to get away, but Mr. Breeze wouldn’t let him go. Mr. Breeze had Peter wrapped up tight and tied in a sleeping bag with just his head sticking out—wriggling like a worm in a cocoon, like a baby trapped in its mother’s stomach.

Even though Peter was nearly twelve years old, Mr. Breeze held him in his arms and rocked him and sang old songs under his breath and whispered shh shhh shhhh. “It’s okay, it’s okay,” Mr. Breeze said. “Don’t be afraid, Peter, I’ll take care of you.”

Читать дальше

![Lord Weller - Ритера или опасная любовь [СИ]](/books/421202/lord-weller-ritera-ili-opasnaya-lyubov-si-thumb.webp)