Outside the neighbors greet each other; the elderly with polite nods or handshakes, the teenagers with shouts and gestured slang. I wonder which of the new greetings used this morning will entrench themselves into the vocabulary of tomorrow.

Social structures follow their own path of evolution—variations infinitely emerging, competing, and fading into the tumult. The cathedral at the end of our street will one day host humans speaking a different language, with entirely different customs than ours.

Everything changes. Everything is always changing. To me, the process is very much like waves hitting the tidal rocks: Churn, swirl, splash, churn… Chaos, inevitable in its consistency.

It should not be surprising that, on the way from what we are to what we are becoming, there should be friction and false starts along the way. Noise is intrinsic to change. Progression is inherently chaotic.

Mother calls me for breakfast, then attempts to make conversation while I eat my buttered toast. She thinks that I do not answer because I haven’t heard her, or perhaps because I do not care. But it’s not that. I’m like my brother when he’s connected to the Vastness. How can I play the game of dredging up memorized answers to questions that have no meaning when the world is changing so rapidly? The heavens stream past outside the windows, the crustal plates are shifting beneath my feet. Everything around me is either growing or falling apart. Words feel flat and insignificant by comparison.

Mother and father have avoided discussing synaptic grafting with each other all morning, a clear indication that their communication strategies must once again evolve. Their conversations about me have always been strained. Disputed phrases have died out of our family vocabulary, and my parents must constantly invent new ones to fill the gaps.

I am evolving too, in my own small way. Connections within my brain are forming, surviving, and perishing, and with each choice I make I alter the genotype of my soul. This is the thing, I think, the my parents most fail to see. I am not static, no more than the large glass window that lights the breakfast table. Day by day I am learning to mold myself to a world that does not welcome me.

I press my hands to the window and feel its cool smoothness beneath my skin. If I close my eyes I can almost feel the molecules shifting. Let it continue long enough, and the pane will someday find its own shape, one constrained not by the hand of humans but by the laws of the universe, and by its own nature.

I find that I have decided something.

I do not want to live small. I do not want to be like everyone else, ignorant of the great rush of time, trapped in frantic racing sentences. I want something else, something that I cannot find a word for.

I pull on mother’s arm and tap at the glass, to show her that I am fluid inside. As usual, she does not understand what I am trying to tell her. I would like to clarify, but I cannot find the way. I pull my ballet slippers from the rustling paper bag and place them on top of the information packet left by the neuroscientist.

“I do not want new shoes,” I say. “I do not want new shoes.”

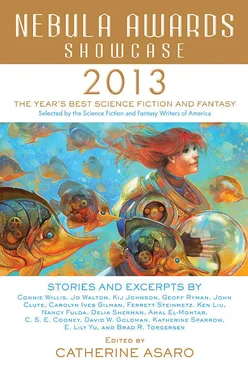

SAUERKRAUT STATION

Ferrett Steinmetz

“The sauerkraut is what makes us special,” Lizzie explained as she opened up the plastic door to show Themba the hydroponic units. She scooped a pale green head of cabbage from the moist sand and placed it gently into Themba’s cupped hands.

She held her breath as Themba cradled it in his palm, hoping: Please. Please don’t tell me that stuff grows everywhere at home.

Themba ran a dark brown finger along the cabbage’s veins, then let loose a sigh of wonder. “That’s marvelous ,” he said.

Lizzie puffed out her chest. Themba had passed her final test. At ten years old, Themba was two years younger, six inches shorter, and eight shades darker than Lizzie was, and she’d known him for a record three days and nine hours. That made him her best friend ever.

Themba leaned in through the access hatch to grab for another cabbage, but one of his escorts hauled him back out by the scruff of his red-and-gold kaftan. Lizzie was sure Themba would protest this time, but he ignored them as always. “You grow that stuff in here?” he asked her. “In space ?”

“Yup,” Lizzie said proudly, watching the escorts inspect the hydroponic basin for traps. “Momma says there are thousands of refill stations across the Western Spiral, but only we have genuine, home-made sauerkraut—one jar for ten indo-dollars, four for thirty. I know captains who chart an extra point on their jump-charts just to take some of our kim-chi home with ’em, yessiree.”

“You gotta tell me how to make this stuff!” Themba stuck a thumb inside the jar of sauerkraut—the escorts had already tested it—and licked the juice off. “I mean, if it’s not a trade secret or anything.”

“It’s pretty simple,” Lizzie said—though secretly, she wondered if Momma would mind her sharing. “I can show you now, if the stoops don’t get in my way.”

“Aw, they’re good eggs. Come on, fellas, give us some room. It’s been three days, it’s not like she’s going to go all homi on me now .”

The escorts squeezed reluctantly back out of the station kitchen, a convenience nook just large enough to allow two people to defrost prefabbed meals for the daily guests. Lizzie could see their muscles flex as they squatted on the aluminum cafeteria benches outside, glaring at Lizzie through the serving window.

Themba’s escorts creeped Lizzie out; they had wrinkle-free faces that never smiled. They were utterly unlike Themba, whose broad, flat-nosed face was so expressive it flickered from mischievous grins to repentant sadness in the twinkle of an eye. Themba wore colorful, flowing robes, his cornrowed hair dotted with beads; his guards wore crisp, gunmetal-gray uniforms.

“I’ve never cooked!” said Themba, rubbing his hands together at the unexpected freedom. “All my food gets brought to me. So when I’m staying with the Gineer heads of state, I’ll make sauerkraut for them. They’ll all ask, ‘Where did you learn this amazing recipe?’ and I’ll say, ‘In space .’”

“That’ll impress them?”

“You kidding? To hear that actual, grown food came from an outpost? In a system with no habitable planets? When I’m done, they’ll all be begging to live in space stations.”

“Themba, you are awesome ,” laughed Lizzie. “I hope your ship’s busted forever.”

Themba blushed. “I love it here, but I need to get to my reward.”

“What’s your reward?”

“I’m gonna be—”

One of the guards stood up, so fast he banged his knee against the cafeteria tables. Themba glanced over nervously.

“It’s a secret,” he whispered. “A state secret. But it’s gonna be awesome.”

If Themba said it was awesome, Lizzie believed him. Themba was the only visitor to Sauerkraut Station who’d ever understood just how awesome her home was.

It was one of Lizzie’s duties to show their guests’ children around for the handful of hours it took Gemma and Momma to resupply their ships. Space travel was both expensive and time-consuming, so the kids were spoiled and cranky. Most wrinkled their noses and told her it stank in here, which it most certainly did not —Lizzie had lived her all her life, and she was sure she would have noticed any funny smells.

Determined to prove how glorious life in space was, she always took them on the full tour, displaying all the miracles that kept her family alive in the void.

Lizzie took them for a walk all the way around the main hallway, explaining how the central, cigar-like axis rotated to give Sauerkraut Station its artificial gravity. She told them why the station looked like a big umbrella—Lizzie didn’t know what an umbrella was, but the dirters always nodded—it was because the axis had a great, solar-paneled thermal hood on the end that shielded them from the sun. That hood simultaneously kept the heat off so they weren’t boiled alive and generated electricity to keep their servers running—a clever design that her great-great-Gemma had pioneered.

Читать дальше