Robert Silverberg - Our Lady of the Sauropods

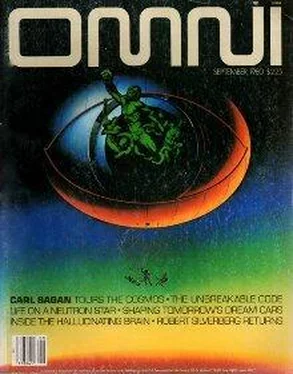

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Silverberg - Our Lady of the Sauropods» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1980, Издательство: Omni Publications International Ltd., Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Our Lady of the Sauropods

- Автор:

- Издательство:Omni Publications International Ltd.

- Жанр:

- Год:1980

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Our Lady of the Sauropods: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Our Lady of the Sauropods»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Our Lady of the Sauropods — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Our Lady of the Sauropods», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Here I go.

1830 hours. Twilight is descending now. I am camped near the equator in a lean-to flung together out of tree-fern fronds—a flimsy shelter, but the huge fronds conceal me, and with luck I’ll make it through to morning. That cycad cone doesn’t seem to have poisoned me yet, and I ate another one just now, along with some tender new fiddleheads uncoiling from the heart of a tree-fern. Spartan fare, but it gives me the illusion of being fed.

In the evening mists I observe a brachiosaur, half-grown but already colossal, munching in the treetops. A gloomy-looking triceratops stands nearby and several of the ostrichlike struthiiomimids scamper busily in the underbrush, hunting I know not what. No sign of tyrannosaurs all day. There aren’t many of them here, anyway, and I hope they’re all sleeping off huge feasts somewhere in the other hemisphere.

What a fantastic place this is!

I don’t feel tired. I don’t even feel frightened—just a little wary.

I feel exhilarated, as a matter of fact.

Here I sit peering out between fern fronds at a scene out of the dawn of time. All that’s missing is a pterosaur or two flapping overhead, but we haven’t brought those back yet. The mournful snufflings of the huge brachiosaur carry clearly even in the heavy air. The struthiomimids are making sweet honking sounds. Night is falling swiftly and the great shapes out there take on dreamlike primordial wonder.

What a brilliant idea it was to put all the Olsen-process dinosaur-reconstructs aboard a little L5 habitat of their very own and turn them loose to recreate the Mesozoic! After that unfortunate San Diego event with the tyrannosaur, it became politically unfeasible to keep them anywhere on earth, I know, but even so this is a better scheme. In just a little more than seven years Dino Island has taken on an altogether convincing illusion of reality. Things grow so fast in this lush, steamy, high-CO 2tropical atmosphere! Of course, we haven’t been able to duplicate the real Mesozoic flora, but we’ve done all right using botanical survivors, cycads and tree ferns and horsetails and palms and gingkos and auracarias, and thick carpets of mosses and selaginellas and liverworts covering the ground. Everything has blended and merged and run amok: it’s hard now to recall the bare and unnatural look of the island when we first laid it out. Now it’s a seamless tapestry in green and brown, a dense jungle broken only by streams, lakes and meadows, encapsulated in spherical metal walls some two kilometers in circumference.

And the animals, the wonderful fantastic grotesque animals—

We don’t pretend that the real Mesozoic ever held any such mix of fauna as I’ve seen today, stegosaurs and corythosaurs side by side, a triceratops sourly glaring at a brachiosaur, struthiomimus contemporary with iguanodon, a wild unscientific jumble of Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous, a hundred million years of the dinosaur reign scrambled together. We take what we can get. Olsen-process reconstructs require sufficient fossil DNA to permit the computer synthesis, and we’ve been able to find that in only some twenty species so far. The wonder is that we’ve accomplished even that much: to replicate the complete DNA molecule from battered and sketchy genetic information millions of years old, to carry out the intricate implants in reptilian host ova, to see the embryos through to self-sustaining levels. The only word that applies is miraculous. If our dinos come from eras millions of years apart, so be it: we do our best. If we have no oterosaur and no allosaur and no archaeopteryx, so be it: we may have them yet. What we already have is plenty to work with. Some day there may be separate Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous satellite habitats, but none of us will live to see that, I suspect.

Total darkness now. Mysterious screechings and hissings out there. This afternoon, as I moved cautiously, but in delight, from the wreckage site up near the rotation axis to my present equatorial camp, sometimes coming within fifty or a hundred meters of living dinos, I felt a kind of ecstasy. Now my fears are returning, and my anger at this stupid marooning. I imagine clutching claws reaching for me, terrible jaws yawning above me.

I don’t think I’ll get much sleep tonight.

22 August. 0600 hours. Rosy-fingered dawn comes to Dino Island, and I’m still alive. Not a great night’s sleep, but I must have had some, because I can remember fragments of dreams. About dinosaurs, naturally. Sitting in little groups, some playing pinochle and some knitting sweaters. And choral singing, a dinosaur rendition of The Messiah or maybe Beethoven’s Ninth.

I feel alert, inquisitive, and hungry. Especially hungry. I know we’ve stocked this place with frogs and turtles and other small-size anachronisms to provide a balanced diet for the big critters. Today I’ll have to snare some for myself, grisly though I find the prospect of eating raw frog’s legs.

I don’t bother getting dressed. With rain showers programmed to fall four times a day, it’s better to go naked anyway. Mother Eve of the Mesozoic, that’s me! And without my soggy tunic I find that I don’t mind the greenhouse atmosphere half as much.

Out to see what I can find.

The dinosaurs are up and about already, the big herbivores munching away, the carnivores doing their stalking. All of them have such huge appetites that they can’t wait for the sun to come up. In the bad old days when the dinos were thought to be reptiles, of course, we’d have expected them to sit there like lumps until daylight got their body temperatures up to functional levels. But one of the great joys of the reconstruct project was the vindication of the notion that dinosaurs were warm-blooded animals, active and quick and pretty damned intelligent. No sluggardly crocodilians these! Would that they were, if only for my survival’s sake.

1130 hours. A busy morning. My first encounter with a major predator.

There are nine tyrannosaurs on the island, including three born in the past eighteen months. (That gives us an optimum predator-to-prey ratio. If the tyrannosaurs keep reproducing and don’t start eating each other, we’ll have to begin thinning them out. One of the problems with a closed ecology—natural checks and balances don’t fully apply.) Sooner or later I was bound to encounter one, but I had hoped it would be later.

I was hunting frogs at the edge of Cope Lake. A ticklish business-calls for agility, cunning, quick reflexes. I remember the technique from my girlhood—the cupped hand, the lightning pounce—but somehow it’s become a lot harder in the last twenty years. Superior frogs these days, I suppose. There I was, kneeling in the mud, swooping, missing, swooping, missing; some vast sauropod snoozing in the lake, probably our diplodocus; a corythosaur browsing in a stand of gingko trees, quite delicately nipping off the foul-smelling yellow fruits. Swoop. Miss. Swoop. Miss. Such intense concentration on my task that old T. rex could have tiptoed right up behind me, and I’d never have noticed. But then I felt a subtle something, a change in the air, maybe, a barely perceptible shift in dynamics. I glanced up and saw the corythosaur rearing on its hind legs, looking around uneasily, pulling deep sniffs into that fantastically elaborate bony crest that houses its early-warning system. Carnivore alert! The corythosaur obviously smelled something wicked this way coming, for it swung around between two big gingkos and started to go galumphing away. Too late. The treetops parted, giant boughs toppled, and out of the forest came our original tyrannosaur, the pigeon-toed one we call Belshazzar, moving in its heavy, clumsy waddle, ponderous legs working hard, tail absurdly swinging from side to side. I slithered into the lake and scrunched down as deep as I could go in the warm oozing mud. The corythosaur had no place to slither. Unarmed, unarmored, it could only make great bleating sounds, terror mingled with defiance, as the killer bore down on it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Our Lady of the Sauropods»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Our Lady of the Sauropods» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Our Lady of the Sauropods» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.