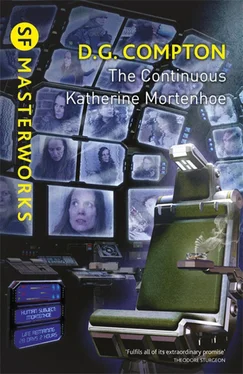

D. G. Compton

THE CONTINUOUS KATHERINE MORTENHOE

Although it could hardly be said to exist at that time, ‘Reality TV became a talking-point and cause for concern in 1974, following the broadcast of An American Family, a fly-on-the-wall documentary series which aimed to capture the truth of real people’s lives and relationships by focusing on the Loud family of California. It was just one series, but it seemed a portent of the future, when there would be cameras everywhere turning ordinary people into celebrities and serving up their problems, conflicts and emotions as entertainment for the masses.

I was a television critic as well as a science fiction writer in the 1970s, and remember that even though An American Family had few imitators (in Britain there was The Family a year later) -partly because it was a slow, expensive, labour-intensive way of making programmes with the technology of the day — the series had a powerful effect on the popular imagination. It led to arguments and discussions about the influence of the camera — and implied audience — as catalyst rather than a passive recorder; as something that created the very drama it was meant to be observing, by inspiring people to perform. If they weren’t being watched, would Pat have demanded a divorce from her husband of twenty-plus years? Would their son Lance have come out in public as gay? Critics and commentators wondered about the alienating effect of lives played out on screens, about exploitation, about the truth of this so-called ‘reality’. Privacy and relationships were being destroyed and the pain of real people turned into popular entertainment — to sell more products (in fact, An American Family aired on PBS, a non-commercial network. But we thought we could see the way the wind was blowing).

D.G. Compton’s novel, first published in 1974, was part of the Zeitgeist, possibly even ahead of the curve. In the US, The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe was published under the simpler, more sinister title The Unsleeping Eye. The eye in question is that of Roddie, a visual journalist so convinced by his own ability to capture the truth on film that he’s had his eyes replaced by cameras, enabling him to get up close and personal without his subjects realising he sees things they might rather hide.

Roddie has been hired by NTV to shoot the latest edition of a documentary series called Human Destiny which follows the experiences of people confronting the ends of their lives, with the high-sounding aim of ‘total truthfulness about the human condition’. In this near-future Britain, developments in medical science mean that almost no one dies of anything but extreme old age (unless they are hit by a car), and as a result the public is ‘pain-starved’. People’s need for some sort of regular psychic jolt has made Human Destiny the highest-rated programme on television. Stricter privacy laws also mean that the TV companies and newspapers find it hard to exploit the pain of others without buying their consent.

But Compton’s real interest here is not issues of privacy, or the future of the media, or whether watching TV is bad for you (although he has his viewpoint character say, ‘Certainly human behaviour had changed since the coming of TV behaviour’), but rather with the eternal question of how we are to live, how to be true to ourselves, whatever happens.

Katherine Mortenhoe knows she will soon die; the problem she faces is how to make the best use of her final weeks. What matters the most to her? Roddie is determined to find out. At first, his interest is only professional curiosity and their relationship is one of mutual deception, but that changes, along with Roddie’s realisation that it is not enough to present unmediated images and call it truth: it’s the mind behind the eye that gives meaning. He must, as urgently as Katherine, make a decision about what really matters.

There was no Internet in 1974; no Twitter or YouTube or Facebook; video cameras were large and bulky objects, and even the cheapest films were expensive to make and distribute. Today’s reality, when almost any college student can make a video in his own room, with no budget, and display it to a world-wide audience within minutes for no financial reward, was a development I don’t think anyone could have imagined back then.

But questions about how to live a meaningful life have not gone away, and will never be satisfied by changes or improvements in technology. The story Compton tells is a bleak one (although enlivened by his sharp observational humour), yet, in the end, unexpectedly conveys a message of hope. Love and honesty matter more than money or fame, and redemption is in our own hands, whatever they try to tell you on TV.

Lisa Tuttle

Katherine Mortenhoe… So now I had a name to work on, and a case history. I also had NTV’s background report. The last two would be of little help. The facts in the case history and the background report — chopped arbitrarily, like photographs, out of continuous time for the neatest of reasons — were therefore untrue. Untrue, that is, in the largest sense.

The name was more useful. Mortenhoe being the surname of her first husband retained into her second marriage and preferred for some reason to her maiden name, it must at least be indicative of something…. Affection for Gerald Mortenhoe, perhaps? Or for the state of being Mrs Mortenhoe, of having been Mrs Mortenhoe? Or possibly simply indicative of a need to be polysyllabic. Her second husband’s name was far duller.

I was picky over the name because it was all I had to go on, all I had that was continuous and entirely hers. I had this thing about continuity, you see, having long ago decided that people were only true when they were continuous. As an attitude, an approach to my job as a reporter, it had done me very well. It had got me where I was at that moment. Also it was a game that filled in the time nicely until the arrival in the flesh of the only true, continuous Katherine Mortenhoe.

It will be noticed that I was at that time very much concerned with what I saw as the truth.

I had read the case history and the background report over coffee in the NTV canteen. The facts in them, partial though they were, had aroused in me a compassion that regrettably my more recent thinking about the name was rapidly dissipating. I was coming down in favor of the need to be polysyllabic, and that sort of status-seeking bored me. Now I sat with Vincent and waited for the only true Katherine Mortenhoe to appear on the other side of the one-way mirror. I don’t remember that I asked him his opinion of the matter. I had prejudices enough for both of us.

Monkeys seldom sit. Likewise, only even less so, bare-assed Homo sapiens, man in the Garden, man before the Fall. His rump just isn’t that tough. So it might be said that the ease with which today we park our bald and flaccid bums at the slightest excuse represents the finest flower of our civilization. Be that as it may, at that time whenever I sat and became aware that I sat I felt squalid. I felt lax, despicably passive, as if my ass were some gigantic parasitic sucker clapped onto the rest of creation. I would fidget. I would lift apologetically first one side and then the other, proving it wasn’t really so. I would fancy I could hear the plop.

‘Nervous?’ said Vincent, smiling his smile.

Since I had in fact been thinking entirely about the name Mortenhoe and what it might signify, the shifting had to be a neurotic reflex. I settled both cheeks firmly to suck.

Читать дальше