Time slipped by and I did not leave. I might be there yet, had I not fallen off a ladder.

WHEN I WAS TOLD THAT THREE-BLUE HAD RETURNED from yet another mission, I was disgusted to realize that it must have been his fifth, while I was still just frittering my life away in Heaven, achieving nothing. I found him in the scriptorium, in bright sunlight and the usual clutter, with Gabriel and half a dozen worried saints.

Quetti was one of the senior angels now. His dimple had become a cleft and scalp showed through the golden hair, but otherwise he was little changed. His grin of welcome was broad enough, but brief. I envied him his tan. Sunshine was one thing I missed badly. In Heaven, the sky is not only often cloudy and dull, but actually dark about half of the time, an unnatural and unwholesome condition that always reminded me of mine tunnels.

“Roo?” Kettle’s voice boomed across the big room as I entered. “Now I know we have a problem—Roo’s here!”

“Always glad to help out,” I agreed. They knew why I always turned up when there was a problem.

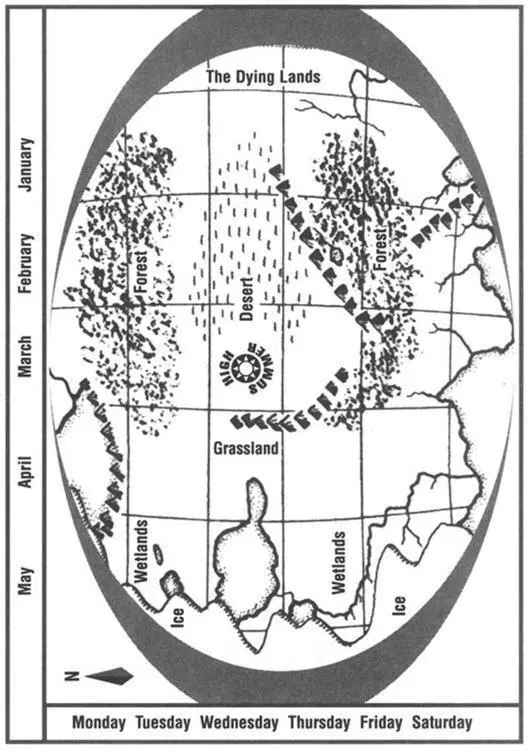

Quetti had been dispatched far to the northwest, to where the Alps were emerging from Dawn’s ice sheets. As the sun crosses March in every cycle, meltwater builds up north of the range in a gigantic lake. The tundra drainage freezes off at just about the time the icecap clears the western end of the barrier. The result is the Great Flood, a catastrophe in the wetlands. It had been the height of the lake that Quetti had been sent to inspect.

But angels’ field reports never quite agree with those from previous cycles, because the geography is always changing. The saints’ job was to turn Three-blue’s notes into maps, and maps into predictions.

Kettle was leaning over the big table again, growling. “This is impossible! Blind wetlander! Michael should have sent a seaman!”

“Three-blue’s a match for any seaman,” I said, winking at Quetti.

Kettle just muttered, attending to the task at hand.

Somewhat later—at about the time my stomach’s rumblings became louder than the snortoises—we had reached a consensus. Not only was the lake too high, but the ice was receding too fast. Moreover, the Great Flood had been coming earlier every cycle, and no one had noticed that trend. We made notes all over the current reports to warn the saints in the next cycle—but that didn’t solve the problem. The timing looked very bad.

At length, Quetti left the learned men to their disputations and took me aside. He perched one hip on the edge of a desk, blithely upsetting carefully stacked papers. “I’ll get this one?”

“You want it?”

He nodded, so I nodded. “Likely you’ll get it, then.”

He smiled briefly. “How’s the equipment situation?”

“Same as usual,” I said. “Drivers’ll be your headache. There are four ant armies on the move just now.”

Quetti made a lewd remark about ants and the impossibility of angels ever keeping them honest. “Who’s around?”

I listed the angels presently in Heaven, starting with seamen and wetlanders; he nodded or pouted as I went along, rarely having to ask for details on one he didn’t know. I left out a few who were too old or sick, and I included Two-gray, whose broken leg was almost healed, and White-red-white, whom Quetti disliked.

By the end, his face was grim indeed. “Seven? Only seven of us?”

“You want rough-water sailors, them’s your choice.”

He muttered an oath, his blue eyes staring bleakly past me at unseen horrors. I felt very, very glad that I was not in his place. Seven men could never warn all of the wetlanders in time. They would get caught by the flood, and more than likely that mean Scroll of Honor. Another disaster Heaven had failed to prevent!

Blots, the scriptorium’s snortoise, had started slithering down a long slope. Saints muttered angrily as their light failed.

Quetti turned that cold glare on me and cocked an eyebrow.

“Fancy a little fieldwork for a change?”

I suppressed a shiver. “Oh, I’d love to help you out. But Michael just can’t bring himself to give me my wheels.”

My feeble attempt at humor was ignored. “I’m serious. This is going to be a bad one, Old Man.”

“You’re crazy!” I said hastily. “I’m no rough-water sailor.”

“I’ll cook breakfast while you’re learning.”

I told him firmly that if he wanted angels just so he could drown them, then we had a plentiful supply better qualified than me.

“Some may be seamen or wetlanders,” he said, “but you’re both! I know how fast you pick up things. Well, do this one for me—seven men and seven chariots for the mission. Double drivers to get them there faster. Three per cart coming back, naturally. How many to start?”

Was this some sort of trick? “Twenty-eight men and fourteen chariots, of course.”

His smile was almost lost in the gloom. “See? I tried to do that sort of sum all the way back from April, and I never came up with the same answer twice.”

Gabriel had adjourned the meeting. Daylight had gone, and candles were not allowed in the scriptorium. A saint nipped out to raise the flag over the door, an appeal for dogsleds. Quetti and I told the others to go ahead, being happy to sit and talk angel talk. With cherubim I talked cherub talk, and seraph talk with seraphim. I had no group of my own.

─♦─

We two were the last. We went out to the porch and began pulling on damp-smelling furs. Judging by the racket outside, Blots had found a thick grove of dead trees buried in the snow of the valley bottom. He was likely to remain there for a considerable time, until complete darkness and falling temperatures triggered his primitive reflexes. Then he would go looking for the sunset again.

Without warning, Quetti said, “Roo? Why won’t you ask for your wheels? There’s so much to be done, and so few of us to do it!”

“Ah! Three-blue, you are treading close to one of Heaven’s great mysteries, one of Cloud Nine’s favorite philosophical debates! Is it even worth doing everything you can, when it amounts to so little compared to what’s needed? I’ve noticed that eager young cherubim never doubt. ‘Of course!’ they say. But the rheumy old saints and retired angels—they usually shake their heads. Men even older than me, each one of them looking back on a whole lifetime of achievement and seeing that it doesn’t really amount to anything at all. None of us is going to change the course of history, Quetti, so why—”

“Stop evading the question.”

I hauled at legging laces, doubled over and unable to speak.

“Knobil, you’d make a great angel,” Quetti said.

I unbent slightly. “You know why Michael couldn’t give me my wheels, even if I asked for them. Everyone knows, so you must.”

“That is plain idiocy!” Quetti said hotly. “You came to Heaven by pure accident. The Compact wasn’t designed to prevent accidents, it was designed to stop men setting up dynasties. Heavens, Roo, you’re not going to set yourself up as a king!”

I went back to my lacing without commenting.

“Have you asked him?” Quetti persisted.

I did not have to answer that either, because a dogsled came yelping and jingling over the snow, following Blot’s wide track. Quetti held the door for me to go first, and I stepped out on the platform, reaching for the rail at the top of the ladder. Far to the east, the sky was black and twinkling with stars, the Other Worlds. Rail and platform were both slick with black ice. Without warning or understanding, I was airborne.

Читать дальше