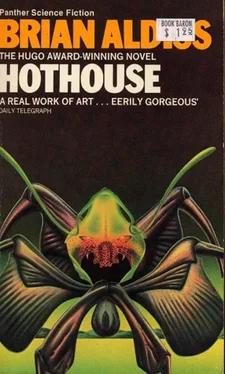

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Don't mourn too much for Poyly. She was fine in life – but a time comes for all of us to fall to the green. I am here now, and I will be your mate.'

'You will want to get back to your tribe, to the herders,' Gren said miserably.

'Ha! They lie far behind us. How shall I get back? Stand up and see how fast we are being swept along! I can hardly see the Black Mouth now – it's no bigger than one of my nipples. We are in danger, O Gren. Rouse yourself! Ask your magical friend the morel where we are going.'

'I don't care what happens to us now.'

'Look Gren -'

A shout rose from the Fishers. They showed a sort of apathetic interest, pointing ahead and calling, which was enough to pull Yattmur and Gren up at once.

Their boat was rapidly being swept towards another. More than one Fishers' colony grew by the banks of the Long Water. Another loomed ahead. Two bulging Tummy-trees marked its position. This colony's net was out across the stream, its boat resting against the far bank, full of Fishers. Their tails hung over the river along the top of the net.

'We're going to hit them!' Gren said. 'What are we going to do?'

'No, we shall miss their boat. Perhaps their net will stop us. Then we can get safely ashore.'

'Look at these fools climbing on to the sides of the boat. They'll be jerked overboard.' He called to the Fishers in question, who were swarming over the bows. 'Hey, you Short-tails! get down there, or you'll be flung into the water.'

His cry was drowned by their shouts and the roar of the water. They were rushing irresistibly toward the other boat. Next moment they struck the net that stretched across their path.

The cumbersome boat squealed and lurched. Several Fishers were flung down into the water by the impact. One of them managed to jump the narrowing distance into the other boat. The two vessels struck glancingly, cannoned off each other – and then the securing rope across the river broke.

They whirled free again, to go racing on down the flood. The other boat, being already against the bank, stayed there, bumping uncomfortably. Many of its crew were scampering about the bank; some had been flung into the stream, some had had their tails lopped off. But their misadventures remained hidden for ever more as Gren's boat swept round a grand curve and jungle closed in on both sides.

'Now what do we do?' Yattmur asked, trembling.

Gren shrugged his shoulders. He had no ideas. The world had revealed itself as too big and too terrible for him.

'Wake up, morel,' he said. 'What happens to us now? You got us into this trouble – now get us out of it.'

For answer the morel started turning his mind upside down. Dizzied, Gren sat down heavily. Yattmur clasped his hands while phantoms of memory and thought fluttered before his mental gaze. The morel was studying navigation.

Finally it said, 'We need to steer this boat to get it to obey us. But there is nothing to steer it with. We must wait and see what happens.'

It was an admission of defeat. Gren sat on the deck with an arm round Yattmur, properly indifferent to everything external. His thoughts went back to the time when he and Poyly were careless children in the tribe of Lily-yo. Life had been so easy, so sweet then, and little had they realized it! Why, it had even been warmer; the sun had shone almost directly overhead.

He opened one eye. The sun was quite far down in the sky.

'I'm cold,' he said.

'Huddle against me,' Yattmur coaxed.

Some freshly plucked leaves lay near them; perhaps they had been plucked to wrap the Fishers' expected catch of fish in. Yattmur pulled them over Gren and lay close against him, letting her arms steal round him.

He relaxed in her warmth. An interest in her awoke, he began instinctively to explore her body. She was as warm and sweet as childhood dreams, and pressed ardently against his touch. Her hands too began a journey of exploration. Lost in delight of each other they forgot the world. When he took her she was also taking him.

Even the morel was soothed by the pleasure of their actions under the warm leaves. The boat sped on down the river, occasionally bumping a bank, but never ceasing its progress.

After a while, it joined a much wider river and spun hopelessly in an eddy for some time, making them all dizzy. One of the wounded Fishers died here; he was thrown overboard; this might have been a signal, for at once the boat was released from the eddy and floated off again on the broad bosom of the waters. Now the river was very wide, and spreading still farther, so that in time they could see neither shore.

For the humans, especially for Gren to whom the idea of long empty distances was foreign, it was an unknown world. They stared out at the expanse only to turn away shivering and hide their eyes. Everywhere was motion! – and not only beneath them in the restless water. A cool wind had sprung up, a wind that would have lost its way in the measureless miles of the forest but was here master of all it passed over. It scuffed the water with its invisible footsteps, it jostled the boat and made it creak, it splashed spray in the troubled faces of the Fishers, it ruffled their hair and blew it across their ears. Gaining strength, it chilled their skins and drew a gauze of cloud over the sky, obscuring the traversers that drifted there.

Two dozen Fishers remained in the boat, six of them suffering badly from the attack of the Tummy-trees. They made no attempt to approach Gren and Yattmur at first, lying together like a living monument to despair. First one and then another of the wounded died and was cast overboard, amid desultory mourning.

So they were carried out into the ocean.

The great width of the river prevented them from being attacked by the giant seaweeds which fringed the coasts. Nothing, indeed, marked their transition from river to estuary or from estuary to sea; the broad brown roll of fresh water continued far into the surrounding salt waves.

Gradually the brown faded into green and blue depths, and the wind stiffened, taking them in a different direction, parallel with the coast. The mighty forest looked no bigger than a leaf.

One of the Fishers, urged by his companions, came humbly over to Gren and Yattmur where they lay resting among the leaves. He bowed to them.

'O great herders, hear us speak when we speak if you let me start talking,' he said.

Gren said sharply, 'We will do you no harm, fat fellow. We are in trouble just as you are. Can't you understand that? We meant to help you, and that we shall do if the world turns dry again. But try to gather your thoughts together so that you talk sense. What do you want?'

The man bowed low. Behind him, his companion bowed low in heart-sick imitation.

'Great herder, we see you since you come. We clever Tummy-tree chaps are seeing your size. So we know you will soon love to kill us when you jump up from playing the sandwich game along with your lady in the leaves. We clever chaps are not fools, and not fools are clever to make glad dying for you. All the same sadness makes us not clever to die with no feeding. All we poor sad clever Tummy-men have no feeding and pray you give us feeding because we have no mummy Tummy-feeding -'

Gren gestured impatiently.

'We've no food either,' he said. 'We are humans like you. We too must fend for ourselves.'

'Alas, we did not dare to have any hopes you would share your food with us, for your food is sacred and you wish to see us starve. You are very clever to hide from us the jumpvil food we know you always carry. We are glad, great herder, that you make us starve if our dying makes you have a laugh and a gay song and another sandwich game. Because we are humble, we do not need food to die with..."

'I really will kill these creatures,' Gren said savagely, releasing Yattmur and sitting up. 'Morel, what do we do with them? You got us into this trouble. Help us get out of it.'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.