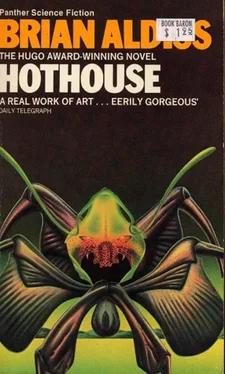

Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Brian Aldiss - Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, Hugo Best Short Story Winner of 1962, we are transported millions of years from now, to the boughs of a colossal banyan tree that covers one face of the globe. The last remnants of humanity are fighting for survival, terrorised by the carnivorous plants and the grotesque insect life.

Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Iccall brushed past these roots and crouched behind a boulder, beckoning them to join him. He pointed ahead.

'There is Black Mouth,' he whispered.

For Poyly and Gren it was a strange experience. The whole idea of open country was completely unknown to them; they were forest folk. Now their eyes stared ahead in wonder that a prospect could be so strange.

Broken and tumbled, the lava field stretched away from them into the distance. It tilted and shaped up towards the sky until it turned into a great ragged cone. The cone in its sad eminence dominated the scene, for all that it stood some distance away.

'That is the Black Mouth,' whispered Iccall again, watching the awe on Poyly's face.

He stabbed his finger to a suspiration of smoke that rose from the lip of the cone and trickled up into the sky.

'The Mouth breathes,' he said.

Gren pulled his eyes away from the cone to the forest beyond it, the eternal forest reasserting itself. Then his eyes were drawn back to the cone as he felt the morel grope deep into his mind with a dizzying sensation that made him brush his hand over his forehead. His sight blurred as the morel expressed resentment of his gesture.

The morel bored down deeper into the sludge of Gren's unconscious memory like a drunken man pawing through the faded photographs of a legacy. Confusion overwhelmed Gren; he too glimpsed these brief pictures, some of them extremely poignant, without being able to grasp their content. Swooning, he pitched over on to the lava.

Poyly and Iccall lifted him up – but already the fit was over and the morel had what it needed.

Triumphantly it flashed a picture at Gren. As he revived, the morel explained to him.

'These herders fear shadows, Gren. We need not fear. Their mighty Mouth is only a volcano, and a small one at that. It will do no harm. Probably it is all but extinct.' And he showed Gren and Poyly what a volcano was from the knowledge he had dredged out of their memory.

Reassured, they returned to the tribe's subterranean home, where Hutweer, Yattmur and the others awaited them.

'We have seen your Black Mouth and have no fear of it,' Gren declared. 'We shall sleep in peace with quiet dreams.'

'When the Black Mouth calls, everyone must go to it,' Hutweer said. 'Though you may be mighty, you scoff because you have only seen the Mouth in its silence. When it sings, we will see how you dance, O spirits!'

Poyly asked the whereabouts of the Fishers, the tribe Yattmur had mentioned.

'From where we stood, we could not see their home trees,' Iccall said. 'From the belly of the Black Mouth comes the Long Water. That also we did not see for the rise of the land. Beside the Long Water stand the trees, and there live the Fishers, a strange people who worship their trees.'

At this the morel entered into Poyly's thoughts, prompting her to ask, 'If the Fishers live so much nearer to the Black Mouth than you, O Hutweer, by what magic do they survive when the Mouth calls?'

The herders muttered among themselves, keen to find an answer to her question. None presented itself to them. At length one of the women said, 'The Fishers have long green tails, O spirit.'

This reply satisfied neither her nor the others. Gren laughed, and the morel launched him into a speech.

'Oh you children of an empty mouth, you know too little and guess too much! Can you believe that people are able to grow long green tails? You are simple and helpless and we will lead you. We shall go down to the Long Water when we have slept and all of you will follow.

'There we will make a Great Tribe, at first uniting with the Fishers, and then with other tribes in the forests. No longer shall we run in fear. All other things will fear us.'

In the reticulations of the morel's brain grew a picture of the plantation these humans would make for it. There it would propagate in peace, tended by its humans. At present – it felt the handicap strongly – it had not sufficient bulk to bisect itself again, and so take over some of the herders. But as soon as it could manage it, the day would come when it would grow in peace in a well-tended plantation, there to take over control of all humanity. Eagerly it compelled Gren to speak again.

'We shall no longer be poor things of the undergrowth. We will kill the undergrowth. We will kill the jungle and all its bad things. We will allow only good things. We will have gardens and in them we will grow – strength and more strength, until the world is ours as it was once long ago.'

Silence fell. The herders looked uneasily at each other, anxious yet self-defiant.

In her head, Poyly thought that the things Gren said were too big and without meaning. Gren himself was past caring. Though he looked on the morel as a strong friend, he hated the sensation of being forced to speak and act in a way often just beyond his comprehension.

Wearily, he flung himself down into a corner and dropped asleep almost immediately. Equally indifferent to what the others thought, Poyly too lay down and went to sleep.

At first the herders stood looking down in puzzlement at them. Then Hutweer clapped her hands for them to disperse.

'Let them sleep for now,' she said.

"They are such strange people! I will stay by them,' Yattmur said.

'There is no need for that; time enough to worry about them when they wake,' said Hutweer, pushing Yattmur on ahead of her.

'We shall see how these spirits behave when the spirit of the Black Mouth sings,' Iccall said, as he climbed outside.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

WHILE Poyly and Gren slept, the morel did not sleep. Sleep was not in its nature.

At present the morel was like a small boy who dashes into a cave only to find it full of jewels; he had staggered into wealth unsuspected even by its owner and was so constituted that he could not help examining it. His first predatory investigation merged into excited wonder.

That sleep which Gren and Poyly slept was disturbed by many strange fantasies. Whole blocks of past experience loomed up like cities in a fog, blazed on their dreaming eye, and were gone. Working with no preconceptions which might have provoked antagonism from the unconscious levels through which it sank, the morel burrowed back through the obscure corridors of memory where Gren's and Poyly's intuitive responses were stored.The journey was long. Many of its signs, obnubilated by countless generations, were misleading. The morel worked down to records of the days before the sun had begun to radiate extra energy, to the days when man was a far more intelligent and aggressive being than his present arboreal counterpart. It surveyed the great civilizations in wonder and puzzlement – and then it plunged back still further, far back, into much the longest mistiest epoch of man's history, before history began, before he had so much as a fire to warm him at night, or a brain to guide his hand at hunting.

And there the morel, groping among the very shards of human memory, made its astonishing find. It lay inert for many heartbeats before it could digest something of the import of what it chanced on.

Twanging at their brains, it roused Gren and Poyly. Though they turned over exhaustedly, there was no escaping that inner voice.

'Gren! Poyly! I have made a great discovery! We are more nearly brothers than you know!'

Pulsing with an emotion they had never before known it to show, the morel forced on them pictures stored in their own limbos of unconscious memory.

It showed them first the great age of man, an age of fine cities and roads, an age of hazardous journeys to the nearer planets. The time was one of great organization and aspiration, of communities, communes, and committees. Yet the people were not noticeably happier than their predecessors. Like their predecessors, they lived in the shade of various pressures and antagonisms. All too easily they were crushed by the million under economic or total warfare.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Hothouse, aka The Long Afternoon of Earth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.